Literature

The literature in Bosnia and Herzegovina is closely related to other South Slavic literature and has often been treated as part of the Serbian and Croatian literature, respectively.

The first known books are church books that date to the 12th century and are mostly written in the Kyrgyz language with Glagolitic or Cyrillic writing. It was not until the 17th century, when the three largest religions in Bosnia and Herzegovina were fortified (Islam, Orthodoxy and Catholicism), that a more extensive literary activity began to emerge. The literature in Bosnia and Herzegovina developed in three directions, all linked to church texts and institutions. Muslims, who previously wrote in Arabic and Turkish, began writing in the spoken South Slavic vernacular, but used Arabic writing (arabica), and a kind of poetry developed in the tradition called alhamiado (alhamijada). Catholics use the same vernacular and Cyrillic script. Despite differences, the three orientations are similar in character because, for the most part, religious writings and chronicles were written. As an example, the Muslim Sarajevo chronicler Mula Mustafa Bašeskija (1731-1805) can be mentioned.

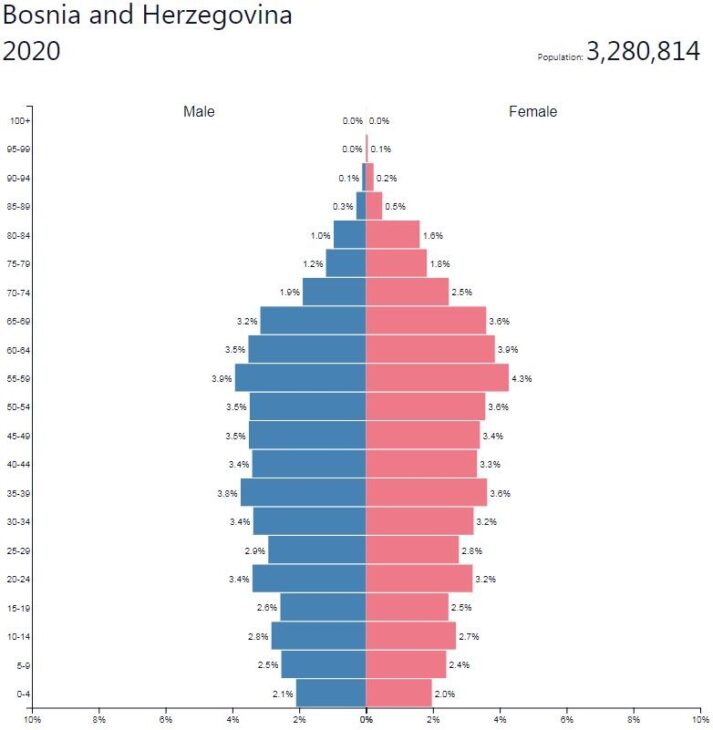

- Countryaah: Population and demographics of Bosnia and Herzegovina, including population pyramid, density map, projection, data, and distribution.

Towards the end of the 18th century, oral poetry became very important for literature in Bosnia and Herzegovina, which was later developed during the 19th century national romance. Modern literature in Bosnia and Herzegovina is described as part of the Serbian and Croatian literature, respectively, while a Muslim literature remains to define and describe. Three of the most important writers in Bosnia and Herzegovina are the Nobel laureates Ivo Andrić, Meša Selimović and the poet Aleksa Šantić (1868-1924). Regardless of the literary traditions they are ascribed (which today is a politically contentious and sensitive issue), these three authors have described in their texts Bosnia and Herzegovina and its people.

After independence, several emigrated writers have described experiences of Bosnia in the war. Aleksandar Hemon (born 1964) and the emigrants to Sweden emigrated Fausta Marianović (born 1956) with the novel “The last bullet I save for the neighbor” (2008) and Zulmir Bećević (born 1982) with the youth book “The journey that began with an end ”(2006).

Film

Before independence in 1992, one cannot speak of a film production in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Yugoslav film was mainly made by companies in Serbia and Croatia. With documentaries such as Serbian Srđan Dragojević’s (born 1963) critical “Flaming Villages” (1996) and, above all, the 1995 establishment of the Sarajevo Film Festival (SFF), while the siege of the city was still ongoing, both stars and international film capital were quickly attracted to the country.

Danis Tanović’s (born 1969) partly French-produced “Ingenmansland” (2001), Oscar-winning as best foreign film in 2002, became an artistic and commercial breakthrough. Tanović followed up in 2010 with “Circus Columbia” and in 2013 with “Epizoda u životu bereča željeza” who won the Silver Bear at the Berlin Film Festival. In 2006, Jasmila Žbanić (born 1974) won the Golden Bear at the same film festival for “Grbavica – does time heal all wounds?” (2006), followed in 2010 by “On the Path”.

Other internationally known filmmakers and films from Bosnia and Herzegovina include Pjer Žalica (born 1964) with “It burns” (2003) and Sabina Vajrača (born 1977) with “Back to Bosnia” (2005). Even Emir Kusturica was born in the country, although he often portrayed life in Bosnia and Herzegovina – among other things. in the comedy “Underground” (1995) – his business is located in and associated with the film industry in Serbia.

See also Yugoslav movie.

Art

The first significant visual artworks were created during the 1300’s and 1400’s, ie. a few centuries after the slaves’ arrival in the Balkans. There are specific tomb monuments found at the necropolis of regions where bogomiles predominated. In 1463, Bosnia and Herzegovina came under the Ottoman Empire, which led to a dominance of Islamic art that lasted for 400 years. The plastic Islamic visual art is exclusively ornamental (arabesque). During the 16th and 16th centuries, a series of icons were created by mainly domestic painters. When Austria-Hungary annexed Bosnia and Herzegovina in the 19th century, a number of painters moved there from different parts of the double monarchy. They created works that are largely descriptive illustrations.

At the beginning of the 20th century, the first generation of painters trained at the Western European academies appeared. They mainly painted motifs from the hometown. This generation is represented by Gabrijel Jurkić, Risto Vukanović, Petar Tješić, Karlo Mijić, Đoka Mazalić and Roman Petrović. A large number of the Bosnian-Herzegovina artists who were active during the interwar period also worked in cultural centers outside Bosnia and Herzegovina, mainly in Belgrade and Zagreb. Among these are Jovan Bijelić, Omer Mujadžić, Ivo Šeremet and Nedeljko Gvozdenović.

During the Yugoslavian period, an emphasis was placed on social themes, represented by, among other things, painters Vojo Dimitrijević, Ismet Mujezinović and Branko Šotra.

After the civil war in the 1990’s, a new generation of internationally active artists has emerged. Installations, performance and photo art are represented in the 21st century by artists such as Brago Dimitrijević, Nebojša Šerić-Šoba, Maja Bajević, Danica Dakić and Sejla Kamerić.

Music and dance

From the Middle Ages to the end of the 19th century, folk music predominated in Bosnia and Herzegovina. It shows great variety and several distinctly different styles. In the mountain regions, old-fashioned Slavic music has been cultivated for outdoor use, predominantly vocals, performed in a high vocal position (in styles such as glass and walking) with strong improvisational elements, short strokes, very small scope and diatonic scales. There are several forms of multi-voting; one performed by three singers at frequent intervals, often seconds, is one of the oldest known in Europe. Younger forms, scattered throughout Bosnia and Herzegovina, are performed with a bourbon, parallel terses or independent voices and a characteristic end to the second tone (na base) of the scale. Common instruments include bagpipe (gajda), shale (flute) and flute (swirl).

In the cities in the valleys and along the routes a Turkish-Oriental influenced music was cultivated, intended for indoor use: unanimous, melismatic (several tones are sung to the same syllable in the text) and strongly ornamented, with long falling melody lines and relatively large scope, performed in low pitch. Popular instruments were long neck sills (tambura, sargija, saz). Especially in the larger cities, an oriental colored love poem (sevdalinke) has been developed. It is still very much alive with well-known artists such as Safet Isović (1936–2007) and Himzo Polovina (1927–86).). Musicians throughout Bosnia and Herzegovina have since the Middle Ages heard wandering singers who accompany themselves on single-stringed lira (gusle) or stringed instruments (pivačka tambura) and sing historical epics, often many hours long.

The dances are predominantly ring and chain dances (colo). Most often they are performed to instrumental dance music, formerly usually played on bagpipes and drums, now by ensembles with accordion, clarinet, violin, bass and guitar. In the 1950’s, in accordance with the new cultural policy, a number of amateur cultural associations were created, mainly devoted to scenic folklore and a number of professional folk music ensembles, including at Radio and TV in Sarajevo. In the 1960’s, in Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina, a form of urban folk music, “newly composed folk music”, emerged with virtuoso singers and accordion which became very popular throughout Yugoslavia.

Western art music and popular music began to develop in connection with Austria-Hungary’s takeover of power in 1878. Military musicians and orchestras were of great importance. Music education was given on a smaller scale in Sarajevo from 1900, and after 1945 music schools were started in several other cities. Sarajevo founded a Philharmonic Orchestra in 1923 and an opera house in 1946. Strong folk music influences are evident in many composers, including Vlado Milošević (1901–88), Cvjetko Rihtman (1902–90), Vojin Komadina (1933–97), Rada Nuić (born 1942) and Branko Grković (1920–82).

After World War II, Western-influenced popular music gained rapid spread. In the 1960’s, the Indexi group became one of the first major pop bands. In the 1970’s Sarajevo became a center for pop and rock, with bands such as Plavi orchestras and Hari Mata Hari. Yugoslavia’s most popular band was Bijelo dugme, with guitarist and later composer of film music Goran Bregović (born 1950). In Sarajevo a hard rock scene emerged in the 1980’s, with the popular band Divle Jagode, and a punk-inspired subculture, “New Primitivism”, with groups such as Dr. Elvis J. Kurtovič & His Meteors and Bombaj Štampa.

After the 1992-95 war, music has slowly recovered. Electronic dance music and hip hop are popular genres, with rapper Edo Maajka (actually Edin Osmić, born 1978) as the latter’s biggest name. Among Bosniaks, Seventh-day and Islamic-colored music (ilahije, kaside) has gained some renaissance. Several of the popular pop and rock bands of the 1970’s and 1980’s, including the Bijelo dugme, have reunited and successfully toured the former Yugoslav republics as symbols of the culture that disappeared with the war.

Folk culture

The popular culture of Bosnia and Herzegovina has deep roots from Slavic, Ancient, Byzantine and Oriental times. Migrations and conversions have also contributed to the diversity of popular culture. The division of the population into Orthodox, Muslims and Catholics has had profound consequences for the shaping of popular culture. The greatest influence can be attributed to the long-standing Turkish dominance, partly through the preservation of age-old cultural patterns of Urslavic origin and partly through the introduction of different cultural elements. For example, Catholics had cross-motif tattoos as a religious marker and an obstacle to Islamization. Particularly Muslim was the circumcision and the late occurrence of fire tests. A common pre-Christian trait is revenge. The role of the three religions in the diversity of popular culture was clearly evident at the customs of life and the year,

Although Bosnia and Herzegovina has long experienced a distinct nation, no Bosnian identity can be mentioned until the mid-19th century. The Prussian settlement was a solitary place, while towns and villages were first established by the Turks. People’s culture is therefore also supported by the urban population. The rural industries constituted Bosnia and Herzegovina’s economic base, of which plum and tobacco cultivation are the best known. In the crafts of the cities, gunsmiths, carpet weavers and copper butchers dominated in Oriental elements – as in the textile folk art – oriental elements, mainly plant motifs. Both in men’s and women’s costumes there are influences from Turkish fashion trends with special pants, the headdress fez and the festive design of the costumes with a lot of jewelry. The Muslims used light, often bright colors while Christians preferred dull, darker colors. The Ottoman influence is also found in the food culture.

The central institution of social life was the large family zadruga with consequences in building condition, ownership, division of work, family affiliation, child rearing, the woman’s extremely subordinate status and family traditions. Nowhere in the Balkans is there such a rich flora of brotherhood as in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Their creation not only resided in a community of interest and mutual assistance, but also served as a defense alliance in the battle between Ottomans and Christians.

The religiously distinctive features of popular culture have, as far as one understands, been reinforced after the war.