Literature

The literature of Finland is written in three languages: Latin, Swedish and Finnish. Up to the major victims (1713-21), 60% of the books were in Latin, 30% in Swedish and 10% in Finnish.

THE MIDDLE AGES

The Latin Saint Henry legend of the 13th century is the oldest known literary text from Finland “Missale Aboense” (1488) contains some fair texts in Finnish. The monk Jöns Budde or Räk (Räck) frequently translated Latin texts into Swedish.

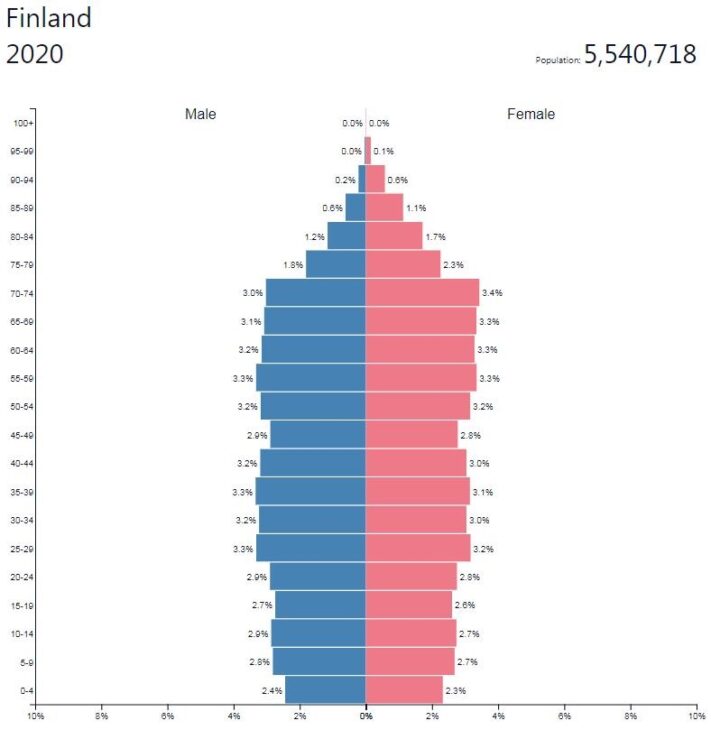

- Countryaah: Population and demographics of Finland, including population pyramid, density map, projection, data, and distribution.

1500’s

Michael Agricola was the first to write and publish books in Finnish. He started with an “Abckiria” (“ABC book”, c. 1540), which in the company contains the first Finnish poem with final rhyme, and continued with a Finnish prayer book (1544) and handbooks on baptism and the Mass. He translated parts of the Bible. In the preface to the Psalter he described in the verses the ancient religious conceptions of the Finns. His Western Finnish dialect became the determining language for Finnish writing.

In 1582 Jacobus Finno edited a collection of “pious songs”, “Piae cantiones”; Of the 74 songs, many have obviously been written in Finland. The collection was translated into Finnish by Hemmingius Henrici in 1616. Finno also published the first Finnish hymn book (c. 1583).

1600’s

The first significant Finnish writer to write in Swedish was Sigfrid Aron Forsius. He was an astronomer, philosopher of nature, priest and translator. His most important scientific work, “Physica” (1611, first printed in 1952) – the first of its kind in Swedish – concludes with a 23 strophe-long “Låf song” for the natural phenomena and the Creator. Forsius also wrote hymns. The Swedish-language literature gained a boost after the arrival of the Turku (old) academy in 1640. Teachers and students wrote occasional poetry, mostly tributes in Latin in connection with disputations, but also in Swedish. Johan Paulinus (adlad Lillienstedt) wrote Baroque-style poems. His epic poem in Greek about Finland (1679) is a precursor to 19th century patriotic poetry. The most significant of the Turkic poets was Jacob Frese.

Finnish-language poets wrote religious poetry in the 17th century. Towards the end of the century, writers writing on the runometer appeared, a verse that had previously been suppressed as a pagan. It was first used by Matthias Salamnius in a two thousand verse long “Ilo-Laulu Iesuxesta” (‘Joyful Song of Jesus’, 1690).

1700’s

The first Finnish collection of poems, Gabriel Calamnius’ “Wähäinen Cocous Suomalaisista runoista” (“A small collection of Finnish poems”, 1755), consists of occasional poems on the runometer. It points forward to the interest in Finnish folk poetry that came a few generations later.

Henrik Gabriel Porthan, the most influential of all professors in Turku, gave in his dissertation series “De poësi fennica” (“About Finnish Poetry”, 1766–78) the first general presentation of Finnish folk poetry.

1800’s

One of the young men who collected Finnish folk poetry in the early 19th century was Carl Axel Gottlund. During his studies in Uppsala he published two collections of folk poems (1818 and 1821) which he had collected in Savolax. A few years later Zacharias Topelius d.a. five booklets of Finnish poems (1822–31), and in the spring of 1828 Elias Lönnrot set out on the first of his twelve voyages to collect folk songs, proverbs and riddles.

Johan Ludvig Runeberg, Johan Vilhelm Snellman and Elias Lönnrot were enrolled in the autumn of 1822 with a few days off at the Turku Academy. These three would dominate Finnish cultural life throughout the century. All three were later included in the Saturday Society, which was formed in Helsinki in 1830 as a forum for discussion of literary and political issues. The members of the society helped to create an awareness of national uniqueness. Runeberg became the national call of Finland with the epic poem cycle “Fänrik Ståls sagner” (1–2, 1848 and 1860) of the 1808–09 years of war. These patriotic, technically masterful poems have, for generations, helped to strengthen the national feeling. The introductory poem “Our Country”, an anthem for the motherland, is in Fredric Pacius’ composition Finland’s national anthem. Runeberg’s wife Fredrika wrote a couple of the earliest historical novels in Finland,

Hegelian Snellman became Finland’s national philosopher. He felt that the Finnish people must be awakened to awareness of their peculiarities through their own Finnish national literature. As a senator, he enforced that the Finnish language was equated with the Swedish as the official language.

Maple Root compiled his collected folk songs into the narrative poem “Kalevala” (1835; new, expanded edition 1849). This work, Finland’s national epic, which has played an important role as a source of inspiration for art, literature and music, is not a reconstruction of some thoroughly weathered ancient epic, but a creation of Lönnrot using genuine folk poetry. He collected a selection of the lyrical and epic folk poems in “Kanteletar” (“Kantelens ma”, 1840–41, published in three booklets).

Zacharias Topelius, the youngest member of the Saturday Society, wrote poems, novels, short stories, plays and fairy tales for children. The romance cycle “Fältskärn’s Stories” (serial in Helsinki Magazines 1851–56, in book form 1853–67) is a depiction of the history of Finland and Sweden from the Thirty Years War to Gustav III’s time. Topelius had a genuinely democratic view of history. Radical positions are also striking in his journalism.

In the mid-1850’s, Johan Julius Wecksell wrote poems that are partly early prohibitions of Finnish-Swedish modernism 70 years later, as well as the drama “Daniel Hjort” (1863), which is still being played.

Aleksis Kivi is the dominant figure in Finnish literature. He is neither highly patriotic nor highly personal in his poems, which are usually unrestricted; he was also accused by his contemporaries of inviting readers to “unearthed gold”. The play “Nummisuutarit” (1864; “Sockenskomakarna”) is one of the most frequently played in Finland. His most important work, “Seitsemän veljestä” (1870; “Seven Brothers”) is one of the great novels in world literature. Kivi had read and learned from Homer, Cervantes and Shakespeare, but he used the lessons independently. The language is colorful and popular, with strong dialectal elements. Kivi died without having experienced any success with his great work. On the contrary, “Seven Brothers” was criticized for general cruelty and lack of language ability by August Ahlqvist-Oksanen,

After the Kivi came a slowdown, but in Minna Canth we again meet one of the great figures in Finnish literature. She more effectively than any other Finnish writer paved the way for the new trends that were moving in European cultural life. Conservative critics dismissed her for “turning upside down on the moral notions” of her godless social criticism, but she has created works as a playwright and novelist, which are still largely living literature. The realist Canth got many followers. The most significant was Juhani Aho, who, however, was more than just a realist. His historical novel “Panu” (1897) is already nationally romantic, and psychological reactions to nature experiences play a major role in his prose sketches. Teuvo Pakkala dealt with class contradictions but also portrayed children with sensitivity and humor. Santeri Ivalo wrote the significant historical novel “Juho Vesainen” (1894; “A peasant chief”). Arvid Järnefelt started out as a realist, but later developed under the influence of Tolstoy’s self-examination and Henry George’s idealistic socialism a strict ethical view of literature.

20th century: Finnish and Finnish modernism

Both writers and visual artists freed themselves from realism during the 1890’s and switched to European symbolism. They praised the joy of life instead of the previously sung poverty and contentment. Eino Leino was the new direction’s foremost representative. He is also the greatest lyricist in Finnish literature. His poem suite “Helkavirsiä” (1–2, 1903 and 1916; “Helkasånger”) is written on Kalevala meter, but expresses a modern sense of life. Equal year with Aho and Järnefelt was Karl August Tavaststjerna, who wrote in Swedish. In his poems he dealt with motifs from the sea and the archipelago. He went the same way from realism to new romance as his Finnish-speaking writers. The same goes for Mikael Lybeck, who in the novel “Tomas Indal” (1911) wrote a variation on the theme “tired men”.

After the turn of the 1900’s, a new realistic flow came in the Finnish prose with Joel Lehtonen, Maiju Lassila, Ilmari Kianto, Frans Eemil Sillanpää, Volter Kilpi and Aino Kallas. Lyricists Eino Leino, VA Koskensemi and Otto Manninen remained new romanticists. Juhani Siljo wrote self-examining poems. The Finnish-Swedish poem was characterized by the “daydreams”, which were inspired by European literary trends. Runar Schildt is the group’s greatest writer.

The writers in both languages were generally nuanced in their view of the war in 1918. Jarl Hemmer, Sillanpää, Aho, Lehtonen and Schildt chose to speak for man, not for man on the red or white side. Of established writers, only Bertel Gripenberg and Kianto were irreconcilable.

The time between the world wars is characterized by the breakthrough and consolidation of modernism in Finnish-Swedish literature. Edith Södergran became a portal figure by transferring expressionism to Swedish-language lyricism. Other pioneers were Hagar Olsson, Elmer Diktonius, Gunnar Björling, Rabbe Enckell and Henry Parland. Modernism’s short-lived but important bodies were the magazines Ultra (1922) and Quosego (1928-29). Important Finnish-language writers gathered in the 1920’s in the group Tulenkantajat (“The Fire Bearers” or “The Torch Bearers”). They were influenced by Finnish-Swedish modernism but also directly by German expressionism and French culture. The members were too different to agree on a more concrete program than “Up with the windows to Europe!”. Leading figure was the cultural critic Olavi Paavolainen. Prominent lyricist in the group was Katri Vala, who wrote free verse and went from romantic modernism to community engagement, P. Mustapää (pseudonym of Martti Haavio), who wrote scholar, multi-layered poetry, Yrjö Jylhä, who embodied his experiences of the winter war in the full-fledged poetry collection “Kiirastuli” (‘Skärselden’) 1941), Lauri Viljanen, who wrote humanist thought poetry, and his wife Elina Vaara and the ethically rigorous Uuno Kailas. Prosaists in the group were Unto Seppänen, who often portrayed the break between Finnish and Russian in Karelia, and Mika Waltari, who mastered all literary genres but is best known for his historical novels. Lyricist Aaro Hellaakoski did not belong to any group. His earliest collections of poems are filled with defiant self-esteem and a healthy natural experience. That period ends with the collection “Jääpeili” (‘Isspegel’, 1928), which has both futuristic and cubist features. Later he wrote poems characterized by a pantheistic sense of togetherness with nature and a strong willed ethical purity. The collection “Sarjoja” (‘Suites’, 1952) is one of the best in Finnish lyric.

In 1936, Marxist-oriented writers formed the bilingual, party-politically neutral group Kiila (“Kilen”) in order to counter fascist currents. Among the original members were the lyricists Jarno Pennanen, Arvo Turtiainen, Viljo Kajava, Katri Vala and Elmer Diktonius, the lyricist and proseist Elvi Sinervo and the proseists Pentti Haanpää and Hagar Olsson.

Despite the connections between writers from both linguistic areas, it took a long time for modernism to seriously penetrate lyricism. A whole new tone is found in Aila Meriluoto’s Rilke influenced collection of poems “Lasimaalaus” (“Stained Glass”, 1946), and in the 1950’s Eila Kivikkaho and Eeva-Liisa Manner finally paved the way for modernism. The Swedish forties read and traced Viljo Kajava and Lasse Heikkilä, the Anglo-Saxon poetry of Tuomas Anhava. Helvi Juvonen wrote anxious poems on Christian grounds, some of them personally modernist. Paavo Haavikko, one of the foremost lyrical modernists, has also written laconically ironic short stories, essays and dramas. Pentti Saarikoski wrote advanced modernist, self-publishing poems.

Part of the post-war prose is on a traditional basis. Most striking is Väinö Linna’s efforts with the novel “Tuntematon sotilas” (1954; “Unknown Soldier”), one of the most compelling war portrayals ever found, and the trilogy “Täällä Pohjantähden alla” (“Here under the Polstjärnan”, 1959-62; in Swedish with separate titles: “High among the Saarijärvi moar”, “Upp thralls” and “Sons of a people”). Linnaeus’s teachers are Tolstoy and Kivi. “Unknown soldier is Seven brothers in the war,” he said. Lauri Viita’s novel “Moreeni” (1950; “Morän”) is about life in a working suburb of Tampere during the 1918 war.

Marja-Liisa Vartio began as a modernist, expressionist colored lyricist based on folk poetry, but in the mid-1950’s switched to multi-layered symbolic prose. Eeva Joenpelto places her figures in a historical and social event and writes a simple, everyday realistic language. Eeva Kilpi is one of the most prominent women painters, both in lyric and prose. The history of modern Finnish prose literature begins in 1957, when Veijo Meri published his breakthrough work “Manillaköysi” (“Manillarepet”), it has been said (Osmo Hormia). Meri merely figures, he does not explain, does not interpret, does not moralize, has no “tendency”. Hannu Salama is one of the left-wing writers who debuted in the 1960’s. His novel “Juhannustanssit” (1964; “The Midsummer Dance”) was praised by the critics but rendered the author a conditional jail sentence for blasphemy. The deal led to changes in the penal code for blasphemy, and Salama was pardoned in 1968. Other important work writers are Alpo Ruuth, Lassi Sinkkonen and Jorma Ojaharju.

In the Swedish language area, Oscar Parland wrote psychological novels, among others. about the mythical world of his childhood. Christer Kihlman has since the 1960’s written mainly self-analytical novels, which are characterized by ruthless openness. Henrik Tikkanen wrote pacifist novels and an autobiographical novel suite where he mercilessly portrayed the life of the Finnish-upper class. His wife Märta Tikkanen writes about women’s problems; The poem suite “The Century of Love Story” (1978) is about the life of an alcoholic wife. Jörn Donner has written numerous novels, but is more significant as a reporter.

Among the lyricists, the modernists strengthened their position during the 1930’s and 1940’s; followers of that tradition are Solveig von Schoultz and Bo Carpelan. The modernists were sharply criticized in 1965 by Claes Andersson, who demanded time awareness and commitment by the authors. He himself writes a powerful, committed poem. Lars Huldén, who also writes critical poems, works more indirectly, with irony and parody.

The legacy of the storyteller Topelius has been well managed. Anni Swan wrote excellent books for children and adolescents, among others. “Tottisalmen perillinen” (1914; “The heir to Tottesund”). Kirsi Kunnas, a modernist-type lyricist and diligent translator, has written a number of appreciated children’s books. Tove Jansson created with his books on life in the Mumindalen (1946-70), where text and image are well matched, a peculiar world characterized by the view of life she founded in her childhood environment. Irmelin Sandman Lilius has also created his own fairytale environment from the 1960’s, the small town of Tulavall. Her imagination has been fueled by popular belief, myths and the literature of romance.

Several writers have written crime novels, including Mika Waltari, Bo Carpelan and Walentin Chorell. From the mid-1970’s, Matti Yrjänä Joensuu has, in a series of literary high-class detective novels, expertly portrayed the work of the police.

Both Juhani Aho and Eino Leino wrote crazies. However, the most masterful of all Finnish cow ears is the signature Olli (Väinö Nuorteva), which hostages the middle class and the bureaucracy. One Swedish-speaking author who also wrote caste series of lasting value is Gustaf Mattsson. Under the heading “Today” he dealt with art, politics, science and current events. A writer on the boundary between science and fiction is Helen af Enehjelm, who wrote essays of cultural and literary historical essays, and Hans Ruin, who analyzed poetry, art and worldviews.

Otto Manninen had four collections of poems as a powerful lyrical work of life but mostly dealt with translations. He interpreted Greek, French, German, Norwegian and Swedish literature into Finnish. Emil Zilliacus, a string of lyricists and a fine essayist, transferred classical Greek literature to Swedish. Thomas Warburton has translated Finnish and Anglo-Saxon literature into Swedish. Lyricist Pentti Saarikoski has translated Greek classics and Joyce into Finnish. Nils-Börje Stormbom, who is also a lyricist, has translated Finnish literature into Swedish. Väinö Linna’s novels.

Many Swedish-speaking writers over the last two hundred years have come from Ostrobothnia. The Swedish Ostrobothnia Literature Association, founded in 1950, tries to manage this heritage, including through the journal Horizon, which, however, is not a provincial body, but has a clear international focus. Among Swedish sister-botanical writers are Anna Bondestam, Hans Fors, Wava Stürmer and Gösta Ågren.

Åland also has its own literature. Sally Salminen’s novel “Katrina” (1936) was a great success in its time. Valdemar Nyman has written a number of historical novels, and Anni Blomqvist depicted the life of the Åland fisherman population. Ulla-Lena Lundberg was born in Kökar, between the archipelago of Åland and Åland. Kökar has provided the environment for her first novels; later she has collected material for her books in America, Japan and Africa. With her, we see how the horizon widened for the Finnish writers in a few decades.

Literature in Finnish in the late 1900’s and early 2000’s

Following the modernist progress of Finnish literature, both lyricism and prose in the 1950’s, new literary trends emerged in the 1960’s, for the lyricism ranging from the novelty of poetry to the anarchist rebellion of Jyrki Pellinen to a conventional, petrified language, Kari Aronpuro’s structuralism and Pentti Saarikoski’s mix of austere modernism, rhetorical debauchery and political themes in eg. “Katselen Stalinin pään yli ulos” (1969; “I look out over Stalin’s head”). Väinö Kirstinä developed a Dadaist, surrealistic and concrete lyric in his poetry collections.

In the field of prose in the 1960’s, Paavo Haavikkos (the greatest name of Finnish prose and lyric modernism) and Antti Hyry’s development of the objective storytelling technique in short stories and novels could see a continuation of the absurdism that Veijo Meri launched in the 1950’s. and the ironic trait of Marja-Liisa Vartio in her tightly structured, symbolic novels, among them “Hänen olivat linnut” (1967; “The Birds Was His”), about various women’s fates.

With the 1970’s came a broad, epic narrative form in the prose, which often consisted of extensive romance suites and thematically revolved around an often nostalgic look back on a bygone rural life. As representatives of this realism and epic are mentioned Eino Säisä, who in his romance suite “Kukkivat roudan maat” (‘The fields of the flower bloom’, 1971-80) takes up precisely the post-war period in the countryside.

Social-critical novels with a working-class origin were also relevant in the 1970’s, including Hannu Salama with his extensive “Finlandia” suite (1976-83) and Alpo Ruuth with prose works on unemployment, the labor movement and emigration to Sweden. The women’s perspective was prominent in writers such as Eeva Kilpi in the erotically charged “Tamara” (1972) and Anu Kaipainen in novels about the lost Karelia or novels that unite mysticism and past themes around the women’s role.

The 1980’s in the Finnish-language prose were characterized by new form experiments and the new subjectivism of Anja Kauranen (now Snellman) in the breakthrough novel “Sonja O. kävi täällä” (“Sonja O. was here”, 1981), a surrealist narcissism at Annika Idström, Esa Sarioals deep dives into spiritual landscapes and Antti Tuuri’s tackling of Ostrobothnian identity in the novel “Pohjanmaa” (1982; “A Day in Ostrobothnia”). Matti Pulkkinen’s “Romaanihenkilön kuolema” (‘The Death of a Novel Person’, 1985) foreshadowed the breakthrough of postmodernism in the Finnish prose. Also Olli Jalonen broke in the novel “Hotelli eläville” (1983; “Hotel for the living”) with the traditional story.

Within the Finnish-language lyric in the 1970’s and 1980’s, a follow-up of past trends and a more everyday, simple form as well as a striving for natural closeness could be discerned and for the 1970’s a further development of a socially oriented poetry including a continuation in 1960 the protest songs of the century. Mention is made of names such as Ilpo Tiihonen, Sirkka Turkka and Kirsti Simonsuuri.

A new young author generation emerged in the 1990’s who developed features of postmodernism and value-nilism in their prose works, as well as avant-garde trends and a tight form awareness in lyricism. Among the lyrics are Jouni Inkala, Lauri Otonkoski and Helena Sinervo, among the proseists Raija Siekkinen with her novelistic absurdism and Juha Seppälä with her grotesque elements.

At the beginning of the 2000’s, the Finnish prose experiences a return to realism alongside the numerous language and structural games that in various forms are included in short stories and novels as well as in lyric. Sofi Oksanen has been one of the most debated prosaists in recent years with her controversial novels “Stalinin lehmät” (2003; “Stalin’s kisses”) and “Puhdistus” (“Reningen”, 2008) about Estonia during the Soviet occupation.

Finnish-Swedish literature in the late 1900’s and early 2000’s

In addition to Christer Kihlman, Ralf Nordgren and Johan Bargum with their formally conscious, socially critical works, the central figures of the Finnish prose in the 1960’s and decades ahead also included Ulla-Lena Lundberg with his rural novels from Åland, Jörn Donner’s critical genealogies (eg “Angela’s War” “, 1976, and” Angela and the Love “, 1980), the versatile Henrik Tikkanen and Märta Tikkanen with her novels on women’s liberation, among them” Men cannot be raped “(1976).

Johannes Salminen continued the Finnish-Swedish essay tradition with critical works on European culture and history. Peter Sandelin continued with his lyric impressionism, Claes Andersson with his ironically-humorous social critical lyric, Lars Huldén with his ingenious language plays, Tua Forsström with his distinct metaphorical lyric and Bo Carpelan with his multifaceted lyric modernism. In the 1980’s, a kind of criticism could be discerned in the Finnish Swedish literature against the 1960’s radicals, a demand for relevant literature that touched on the crises of the then technocratic society.

Alternative movements and action groups also made their mark on the literature. Martin Enckell created nuanced expressive poems in the 1980’s. In the 1990’s, Peter Mickwitz emerged with a distinctly intellectual, image-saturated lyric. In the early 1990’s, interesting proseists also appeared with various personal expressions, including Susanne Ringell, Pirkko Lindberg, who came out with prose works in the late 1980’s, and Monika Fagerholm, who creates a multifaceted, subtextually reflective prose in novels such as “Wonderful Women at Water” (1994), “The American Girl” (2005) and “The Glitter Scene” (2009). Kjell Westö, who debuted as a lyricist, gradually began to profile himself as a proseist with epic traits, which resulted in the family novel “Drakarna across Helsinki” (1996) and “Where we once went” (2006). Thomas Wulff has experimented with the forms of expression in poems and prose works, Fredrik Lång has been linguistically innovative in his prose. Lars Sund emerged as an epic prosaist with a historically profiled theme in “Colorado Avenue” (1991), the first part of a trilogy about an Ostrobothnian village. In the 2000’s, Robert Åsbacka appears with a structurally interesting prose, not least in the novel “The Organ Builder” (2008). In her prose, Merete Mazzarella has continued to discuss both small life, private life and tackled universal issues. Agneta Enckell continues to create suggestive form-lyric lyric and Sanna Tahvanainen a fiercely unconventional view of women in her prose about bleak women’s fate, while Eva-Stina Byggmästar has conducted refined, syntactic experiments in her playfully associative poetry collections. Hannele Mikaela Taivassalo, who made his prose debut in 2007 with a novel about breaking shackles, “Five Knives Had Andrej Krapl”, is both absurd, mythical and metaliterary. In the Finnish-Swedish prose, but also in the lyric in the 2000’s, it can be said that the form experiments became important, as did a diverse view of existential and social issues.

Children’s and youth literature

In Finnish children’s and youth literature, the fairytale has always taken a strong position. Through Zacharias Topelius, children’s literature was established as an independent genre. His “Reading for Children” (1-8, 1865-96) contained a characteristic mix of fairy tales, poems and plays with a direct and close appeal to the children. Anni Swan also wrote mainly stories (1–6, 1901–23) but also youth novels. Nanny Hammarström’s animal stories as well as Viola Renvall’s and Yrjö Kokko’s lyrical children’s stories are other examples. Tove Jansson takes on a special position with her nine Moomin books, picture books and cartoon series (the debut book “The Small Role and the Great Flood” came in 1945). Mumindalen’s contrasts between order and chaos with the secure mother as the central point fascinate both adults and children. The story has retained its position – two recent examples are Irmelin Sandman Lilius, who created the mythical world of Tulavall (Mrs. Sola trilogy 1967–71), and Kaarina Helakisa, who puts a feminist perspective in, for example. “Olena and Vassuska” (‘Olena and Vassuska’, 1979). Leena Krohn is another popular art saga writer. In the 1960’s, realism gained momentum, and the everyday lives of children and adolescents are portrayed, for example, by Bo Carpelan (“The Arch”, 1968), Marita Lindquist (eg, The Malena Books 1964-75) and Margareta Keskitalo (“Tabut”, 1970). The picture book reached a strong position in the 1980’s and 1990’s, thanks to new artists such as Kaarina Kaila, Hannu Taina and Kristiina Louhi.

Drama and theater

The theater as an institution came to Finland relatively late, but the dramatic action nevertheless has traditions, which can be traced back to rites within the hunting culture, shamanistic rituals, pagan wedding and funeral ceremonies, bear hunting rites and village games. In the Finnish-Ugric peoples bear rites, the participants performed dances and drama games to appease the animal. Weddings and ceremonial crying at funerals were part of the women’s tradition. These early forms of acting can be perceived as a kind of herbal theater. The pagan rites were mixed with medieval Christianity, and one example of traditions with this background is the procession games at the “whole festivals” in Ritvala, which continued well into the 19th century. From that time on, there is information about clear theatrical performances.

In addition to the folk tradition, the school system continued to have significance for theater activities. The Swedish great power was about developing the teaching system, where dramatic elements were common at this time. At Turku Academy there was a lively student life, and the dramatic literature sprang up early in the university circles. Performances were performed in Swedish but also in Latin and Finnish. Jakob Chronander’s Swedish-language student comedy “Surge” was erected at the promotion in 1647 and represented a dramatic structure and tradition with roots in the Middle Ages. However, this flowering became short-lived. Strict cleanliness and great sacrifices destroyed the incipient tradition.

1700’s

In the 1760’s, the traveling theater companies also began touring in Finland, often with a very solid repertoire. Their visit extended over time to the cities around the country. The companies were Swedish, German Baltic and with time also Russian. Visiting theatrical performances was an established pleasure, and the performing arts enjoyed great popularity. This century of the ambulatory theater became an important incentive for the creation of a domestic professional theater.

1800’s

The ties to Sweden remained during the 19th century. Swedish theater groups continued to perform, as theater companies that moved in the Swedish country towns often extended their tours to the capital of Finland. During the 1810’s and 1830’s, theater premises were built in Turku, Viborg and Helsinki. At the same time, the local amateur theater became a more appreciated pleasure, and by the middle of the century there was quite a general public spectacle in Finnish, for example. “The Tasker Player” (1845), by Pietari Hannikainen. He also wrote other plays, e.g. “Anttonius Putrunius” or “Antto Puuronen” (1859), a reworking of Ludvig Holberg’s play “Erasmus Montanus”. Zacharias Topelius and Runeberg also wrote several plays.

In 1860 the country’s first modern theater, the New Theater in Helsinki (from 1887, the Swedish Theater) was opened. There, the Finnish performing arts were born, more specifically with Aleksis Kivi’s play “Lea” (1869). The first permanent Finnish-language theater ensemble was the Suomalainen Teatteri, the Finnish Theater, founded in 1872. It arose in close connection with the emergence of the nationality ideology and the creation of a national identity, which also marked the beginning of a development towards a democratic society. During the latter part of the 19th century, therefore, the theater also received a role in the service of public education. Folklore education associations, sobriety, workers’ and youth associations as well as the voluntary fire brigade all conducted active theater activities. The popular amateur theater tradition made a decisive contribution to the development of a dense network of professional theaters in the country and to the theater being able to play an important role in cultural activities and social life. Most theaters have their roots in the lively amateur theater business.

1900’s and 2000’s

Kaarlo Bergbom, the first director of the Finnish Theater (from 1902 Finnish National Theater, Suomen Kansallisteateri), strived to make the dramatic literature classics available in Finnish. The classics (Shakespeare, Molière, Goethe, Schiller), international modern drama and new domestic realistic dramas formed the body of the repertoire. The collaboration with the domestic playwright Aleksis Kivi and Minna Canth resulted in a rich national drama that is still being performed today.

At the theater, a realistic-naturalistic style of play prevailed; The importance of different fashion directions for the Finnish theater has been small. However, in works authored by Eino Kalima, who led the Finnish National Theater in 1917–50, a quest for a new psychological credibility could be discerned. To this also contributed the impression of Konstantin Stanislavsky and of the French innovators in the theater. Stanislavsky’s teachings formed the methodical framework for professional theater teaching that began in the 1940’s. They have remained strong and vigorous in the Finnish theater tradition.

After World War II, modern Anglo-American and French drama captured a position on Finnish scenes, which meant a break with traditional behavior. Absurdism in the 1950’s represented a revolt against the naturalistic theater. Brecht’s drama was an important impetus during the 1960’s. The political theater in the 1960’s and 1970’s was, above all, the directors’ forum. Impressions were obtained from Peter Stein’s Schaubühne in Berlin and Giorgio Strehler’s Piccolo Teatro in Milan. The directors Ralf Långbacka and Kalle Holmberg are among the innovators of the performing arts.

The theater group activities developed during the 1960’s and 1970’s as a revolt against the institutional theater’s repertoire policy, working methods and audience. The emergence of politically engaged theater groups with democratic and flexible organization and few staff members has meant a whole new approach to theater, a new socially critical repertoire and a new way of playing. The groups have had a renewed impact on the entire Finnish theater world and represent different theatrical views and theater cultures; Among them are children’s theaters, dance theaters, puppet theaters and Swedish-language theaters.

Typical for modern Finnish theater is the presence of different styles and performance methods. The institutional theaters, which enjoy great financial support, operate in modern, technically well-equipped buildings. The groups have often sought out from the traditional theater buildings. The director’s art has been developed in the direction of physical theater (director Jouko Turkka) as well as visuality and cross-artistic performances.

The women have traditionally held a strong position within the Finnish theater. Maria Jotuni’s and Hella Wuolijoki’s works, together with Minna Canth’s plays, have formed a classic framework for the domestic repertoire. Female directors also have artistic authority in the Finnish theater.

The social involvement in the Finnish theater has not slowed down over the years. Domestic newly written drama continues to dominate theaters’ repertoire. The Swedish-speaking theater has also held its positions at about ten theaters. One of its leading smaller groups has been Theater Viirus. Even the strong tradition of amateur theater remains alive, nowadays mostly in the form of locally anchored summer games. For a while, Turkka was a typical provocative phenomenon in the Finnish-language theater. In 2007, the young director and playwright Kristian Smeds (born 1970) aroused national sensation with his unmasked stage version of Väinö Linna’s war classic “Unknown Soldier”. He and the director Heidi Räsänen are some of a long line of young and well-trained performing artists,

Finnish theater in Sweden

Through immigration, the strong Finnish amateur theater tradition during the 20th century has been transferred to Sweden. A large number of Finnish-speaking and several Finnish-Swedish amateur groups have been formed. Some of them have been further developed into free professional theater groups that play mainly in Finnish but also in Swedish.

However, the professional Finnish theater in Sweden has long been made up of guest plays from Finland. During the 1970’s, among other things, Vivica Bandler (director of the Stockholm City Theater 1969–79) several well-known Finnish-speaking and Finnish-Swedish guest plays. During the 1970’s, and especially in the 1980’s, the Swedish National Theater sent Finnish-language children’s and adult performances on tours throughout the country with, among other things. Finnish associations, schools and theater associations. In the years 1989–97, the Finnish Riks, a Finnish-language ensemble toured in the Swedish National Theater, toured.

In 2002, Uusi Teatteri was founded, which runs children’s and youth theater in Finnish and collaborates with Theater Västmanland and Riksteatern.

Film

Lumière showed film in Helsinki in 1896, but the first feature film made in Finland, “The Maple Burners”, first came in 1907 and it took until the 1920’s before there was a continuous film production. This was largely due to the censorship and restrictions on Finnish film production by the Russian authorities, especially during the 1917 revolution. After independence, Erkki Karu (1887-1935) formed the first significant film company, Suomi-Filmi (1919-65), fetish movies. In general, the production is characterized from the start by the fact that the films are based on domestic drama, for example. “Karus Byns Shoemaker” (1923) by Aleksis Kivi.

The 1930’s is referred to as the golden era in the history of Finnish film. Karu’s successor as CEO of Suomi-Filmi, Risto Orko (1899–2001), produced popular comedies and Dutch melodramas. His “Inspector at Siltala” (1934) was a love story in a manor environment and became the first Finnish film to be seen by more than 1 million cinema visitors. Valentin Vaala (1909–76) should be mentioned as director of elegant comedies. The very talented Nyrki Tapiovaara (1911-40) directed only a few films, including “The Stolen Death” (1938), before falling in the winter war.

During the war, the audience’s need for movie entertainment was immense. Comedies and (pseudo) historical costume films were produced despite a lack of raw materials. So e.g. directed the legendary production manager of the country’s other major film company Suomen Filmiteollisuus, Toivo Juhani Särkkä (1890–1975), the great success of the “Vagabond roller” (1941) with the entire people’s love couple Ansa Ikonen (1913–89) and Tauno Palo (1908–82) in starring.

The post-war period was reflected in “problem films”. Teuvo Tulio (1912–2000) became famous for passionate love scenes and for the visual strength of his films. The 1950’s were characterized by a certain lack of identity. Of the serious efforts, however, can be mentioned “The White Reindeer” (1952) by photographer Erik Blomberg and the unbeatable audience success “Unknown Soldier” (1955) by Edvin Laine, already a director’s nest.

The economic crisis that hit the film industry in the late 1950’s forced new thinking. Thematically, the 1960’s wrestling year resulted in a wave of realistic documentary-style films, such as “A Cot Under the Back” (1966) by Mikko Niskanen (1929-90) and “A Worker’s Diary” (1967) by Risto Jarva. These films were expressions of the new era, such as “Sixtynine” (1969) and “Women Pictures” (1970) directed by Jörn Donner. However, the audience failed and the annual feature film production dropped to one third, from 29 films in 1955 to 9 in 1965. That year, Suomi-Filmi also went bankrupt. The demands for support for domestic film production led, among other things. to the founding of the Finnish Film Foundation 1970.

Of the directors who made their debut in the 1970’s, Rauni Mollberg is one of the more prominent, among others. the hearty “The Earth is a Sinful Song” (1973) and the new recording of Lina’s “Unknown Soldier” (1985). However, the internationally best known and award-winning directors are the brothers Aki Kaurismäki and Mika Kaurismäki. For a long time, they have emerged as tongues for a minimalist and sometimes absurdist film story about outsiders and losers in society’s margins, including “Hamlet Goes Business” (1987), “Cloud on Operation” (1996) and “The Man from Le Havre” (2011) by Aki and “Helsinki Napoli All Night Long” (1987) and “Honey Baby” (2004) by Mika. Action director Renny Harlinhas also become internationally known but then for the Hollywood career he embarked on after the English-language action movie “Born American” (1986) with, among other things. “Die Hard 2” (1990) and “5 Days of War” (2011).

Around the turn of the millennium, modern big city comedies, romantic melodramas and crime movies with action elements attracted the audience to the cinemas. Pirjo Honkasalo (born 1947), who previously made a number of well-known documentaries, directed the tragicomic family chronicle “The Fire Extinguisher” in 1998. Other audience magnets were the romantic melodrama “A Decent Tragedy” (1998) by Kaisa Rastimo (born 1961) and more comedy-acclaimed films, such as Lenka Hellstedt’s (born 1968) filming 2001 of Kata Kärkkinen’s debut novel “Minä & Morrison” (1999). Popular for both romantic melodies and comedies is Aku Louhimies (born 1968), including “Levottomat” (2000), “Frozen Land” (2005) and “Vuosaari” (2012). Even Dome Karukoski (born 1976) has achieved success with i.a. “Forbidden Fruit” (2009) and “Lapland Odyssey” (2010). Among the more action-oriented directors is Aleksi Mäkelä (born 1969), with eg. “Häijyt” (1999) and “Naughty Boys” (2003), and Timo Vuorensola (born 1979) with the alternatively financed “Iron Sky” (2012).

In 2017 came another new recording of “Unknown Soldier”, again a great audience success, this time directed by Aku Louhimies (born 1968).

Art

THE MIDDLE AGES

The entire medieval art stock is of ecclesiastical origin. It consists of over 800 wooden sculptures from mainly southwestern Finland and al secco paintings in some 40 of the total 75 medieval stone churches along the south and west coasts as well as in Tavastland and Åland. Most of the material comes from the end of the Middle Ages; for the painting especially from 1470-1520. Pure Romanesque style is not represented; among the sculpture, however, the Madonna of Korpo Church, now in the Finnish National Museum in Helsinki, occupies a special position through its dating to about 1200 and stylish connection to, among other things. The Wrap Lumina from Gotland. Of the paintings, the oldest are in Åland, in the churches in Jomala, Lemland and Sund. They date to the 1280’s. Paintings from the 1300’s are rare and fragmentary. From the middle of the 13th century, the stock of wood sculptures is increasing. It was a long time of imports, first from southern Sweden and Gotland, later also from Uppland. In the 1300’s, works from Danzig, Hamburg and especially Lübeck dominated. From the 1440’s, altar cabinets were also imported from Antwerp (located in Vånå, Tavastland) and Brussels. It is difficult to determine what is import and what may be of domestic origin. The old theory of a Lundo master, effective about 1325–50, must be carefully re-examined in the light of what we know today.

The most significant import work is the Barbara altar by Meister Francke (formerly in the church in Kaland, now in the Finnish National Museum), carried out around 1410. How and when the cabinet ended up in the small church is unknown. Another significant work is that according to an old assignment 1429 with engraved brass plates decorated St. Henry’s kenotaph in Nousi’s church, ordered by Bishop Magnus II Tavast in Turku, apparently in Flanders. In addition to the cover plate with Sankt Henrik, it includes 12 plates with motifs from the saint’s life and legend.

Stylistically, the lime painting during the 1400’s is fragmented and irregular but interesting through an obvious popular primitivism of various kinds: one in Southwest Finland – among other things. in the churches of Nousis, Korpo and St. Marie – another in mainly eastern Uusimaa. From 1470, Finland’s church painting entered its richest phase, when it educated in Uppland and through its ornamentation to the Tierp school, Petrus Henriksson Pictor began his long and school-forming activities in Southwest Finland with a series of paintings in Kaland’s church. He and his workshop have also performed significant painting suites in Sagu, Letala, Pargas, Tövsala and S: t Karins. This painting is constructed according to a strict theological program. From 1500 to 10 the churches in Ingå, Sjundeå and Espoo have interesting but fragmentary paintings of a more primitive type. The highlight of the epoch is the painting suites from 1510-22 in Lojo and Hattula churches. Hattula has the most motifs of all churches in Finland – 180. – while Lojo with its 172 motifs has the largest painted wall surface. The last medieval embellishments include the vault paintings in the Romano Franciscan Church and the paintings covering the monotonous church in Kumlinge (Åland). It is now clear that around 1514 Lars Snickare from Stockholm made both primitive and renaissance inspired paintings in Rimito church.

Renaissance and Baroque

The Reformation and Gustav Vasa’s withdrawal of the properties of the church and monastery became a harder blow to the culture than in Sweden. For a long time, the royal power also remained the sole commissioner of the arts. This can be noted in the first preserved profane paintings, murals from around 1530 in the concierge’s chamber at Turku Castle, which with example in German graphics depict, among other things. a love couple and a battalion scene. A unique result of an individual’s interest and patronage is the painting suite made around 1560 – remarkable even with Scandinavian dimensions – that the priest Jacob Geet had painted in Storkyro 1300’s church in Ostrobothnia. The paintings fill in three rows all the walls of the church. They form a suite similar to those in Hattula and Lojo but have a more modern visual world through their graphic models from the 1540’s and 1550’s. The transition to the Baroque took place during the time of the great power, when the high nobility became the main commissioner of church decoration. Especially Henrik Klasson Fleming made known for donations of pulpits, including to Turku Cathedral and the churches in Naantali, Tövsala and Virmo. Of the poorly preserved painting in wooden churches, Pyhemaa’s paintings from 1667 can be mentioned, made by Christian Wilbrandt. Lars Gallenius performed paintings as well as church paintings (the Corvette of Torneå church in 1688). Among the graves, they take over Henrik Klasson Fleming and his wife in Virmo church (1632) and over Åke Tott and his wife Christina Brahe in Turku cathedral (1678) a place for themselves in the Baroque of Finland.

One of the more significant portrait painters in Finland at the end of the 1600’s was Diedrich Möllerum, who was probably born and died in Sweden but during the 1680’s and 1690’s performed portraits and epitaphs in Finland. An early contribution also as a landscape painter was made by the German Jochim Langh, who in the castle of Villnäs in the early 1660’s carried out an extensive decoration suite on the order of the admiral and the Council of Ministers Herman Fleming. The castle church, now the parish church in Mietois, erected in 1653 and one of Finland’s few stone churches from the 17th century, can also exhibit a Baroque interior unique to Finland, among others. gentry platform.

1700’s: Late Baroque, Rococo and Gustavian style.

The many wars undermined the development opportunities for the arts; in particular, the first half of the century is very much a white spot in art historical terms. Style historically, rococo is also very poorly represented, while the Bedouin Stavian style or the new antiquity is somewhat better represented. The church and a now burgeoning bourgeoisie again – especially in Ostrobothnia – gave decoration painters a chance, and in the increasing number of mansions in Uusimaa and Southwest Finland, even the counterfeiters were commissioned. One who worked successfully for both of these groups, along with the small circle of teachers and priests at the Turku Academy, was the Stockholm-born Margareta Capsia, known as Finland’s first female artist. Of her altarpieces, “Communion” from Pedersöre, in 1725 (now in the Finnish National Museum) has become most famous. Of the older Ostrobothnian church jewelery, Johan N. Backman was active in the 1750’s and 1760’s. His most extensive decoration can be found in Kronoby church. For 70 years, Mikael Toppelius developed tremendous productivity in 35 churches. With him, Baroque models from Rubens and Merian are mixed with frames in rococo. With his activities, the Ostrobothnian church painting culminates and ceases. Emanuel Granberg, who was often confused with Toppelius, was only active during the 1770’s and 1780’s. Profant decoration painting is mainly represented by Jackarby farm (Borgå parish) sals decoration (now in the Finnish National Museum) from about 1760. Of the portrait painters from the middle of the century, Isak Wacklin from Oulu is unique; he was a time student of Pilo in Copenhagen and during a trip to the UK took the impression of painting there. If his famous works are few, in return over 130 portraits of Nils Schillmark are preserved. He was born in Sweden but came to Finland in 1773, where he was active in Helsinki and Sveaborg but also in the Lovisa region of Uusimaa. As a still-life painter he became a pioneer in Finland. Already in the 1760’s, the art and cultural life of the fortress Sveaborg, built in 1748, had gained momentum through efforts by, among other things. Augustin and Carl August Ehrenswaard and Elias Martin.

1809-1917

Even after 1809, Stockholm was a popular educational destination for Finnish artists. This also applied to the three foreground figures that began the 19th century art. The sculptor Eric Cainberg was brought back to Finland in 1813 to perform six reliefs for the banquet hall in the new house for the Turku Academy. These depict Kalevala motifs and historical motifs, at the same time as influences from the artist’s Rome stay were evident. Turk-born Alexander Lauréus traveled to Stockholm in 1802 to study painting and stayed there. Gustaf Wilhelm Finnberg also came to Stockholm in 1806, but he returned to Turku and painted altarpieces and portraits there until the great fire in Turku in 1827 deprived him of his living possibilities and forced him back to Stockholm. He has rightly been called “the grandfather of Finnish art” when a pupil to him, Robert Wilhelm Ekman, called his “father”. Ekman traveled to Sweden as well as Lauréus twenty years before, but returned to Finland in 1845. For twenty years he became a supported producer of altarpieces, public life portraits and portrait paintings. After 1866, his idealism gave way to other styles. Among his many pupils were also Ferdinand von Wright, the youngest of the three brothers who became known for his animal pictures.

Werner Holmberg’s cometary career in Düsseldorf from 1853 brought with one punch Finland’s landscape painting up to then European level, and for a long time ahead, Düsseldorf would also become a popular educational destination for Finnish artists as well. At the same time, they also had a much needed contact with like-minded people from the other Nordic countries. Among the artists who specialize in landscape painting are Hjalmar Munsterhjelm and Berndt Lindholm, of whom the latter, however, was early grasped by the news of Parisian art. The most promising of figure and genre painters among Finland’s Dusseldorf people was Ålander Karl Emanuel Jansson. Among the Finnish artists who moved from Düsseldorf to Paris were Fanny Churberg.

Although the Finnish Art Association was founded in 1846 and started a drawing school in 1848 and in 1849 took over an older private school in Turku, educational opportunities for sculptors were lacking. Cainberg’s predecessor had to wait for imitation. Instead, a pioneer of modern sculpture became the Swedish Carl Eneas Sjöstrand, who for 40 years trained two generations of sculptors. After studying in Rome and Paris, Walter Runeberg established himself as the leading monument sculptor in Finland from the 1870’s. Painters such as Albert Edelfelt studied for Sjöstrand, but he came to Paris via Antwerp, which thus became a “capital of art” for Finnish artists under 40 years. In the future, the art in Finland would also follow the current European style trends, but not without resistance from home. Realism in Paris soon rose to naturalism. Axel Gallen-Kallela achieved his first success in this style, which aroused much discussion at home in Finland. Helena Schjerfbeck also underwent a period of realism and was awarded the “Convalescent” (1888) medal at the World Exhibition in Paris 1889. A highlight of naturalism was Eero Järnefelt’s painting “Sved”, also called “Trelar under the money” (1893). Also for sculpture, the 1880’s meant a period of brilliance: Walter Runeberg’s eclectic classicism was now replaced by realism. He had his strongest competitor in Johannes Takanen, but most clearly the realism is represented by Robert Stigell, who was strongly influenced by French sculpture. The symbolism of the 1890’s received a surprisingly rapid response from the younger ones, among other things. Magnus Enckell’s moody and Ellen Thesleff’s dreamed-up figure studies. More important, however, became the connection to national motifs such as “Kalevala”. Although Edelfelt led the way with “Christ and Magdalene” (1890), it was Gallen-Kallela who in the 1890’s created the foremost synthesis of naturalism, symbolism and Kalevala motifs. It became his most enduring effort. Gallen-Kallela’s pupil in graphics Hugo Simberg is the foremost representative of the second generation of symbolism. Within the sculpture, Ville Vallgren in Paris achieved international success with strongly Rodin-inspired sculptures. Emil Wikström stood for the increasingly patriotic national line. At the World Exhibition in Paris in 1900 the Finnish artists achieved success, but the political events in their homeland, where not even the impressionism was accepted, appeared to be strongly inhibiting the development of art in the following decade. A Munch exhibition in 1909 in Helsinki became a source of inspiration for the artists, and many of the younger ones staying in France performed cautious experiments in new styles, for example. Valle Rosenberg, Alvar Cawén and Marcus Collin. Widespread art criticism began to emerge and new art salons were added, such as Gösta Stenmans and Sven Strindbergs, where in 1914 works by the group Der Blaue Reiter were shown, among others. some abstract Kandinsky works. Artists such as Juho Mäkelä and Tyko Sallinen belonged to Stenman’s often highly debated “stable”. For the first time now, two artist groups also appeared in Finland; partly one who, at his third exhibition in 1914, took the name Septem, and another who at his second exhibition in 1917 called himself the November group (fi. Marraskuun ryhmä). The polarity and rivalry between the groups has been exaggerated in the past, but there were significant differences in style; Septem represented a French, partly neo-Impressionist style, while the guiding principle for the November group was expressiveness. The leader of the latter group was the already legendary Sallinen. At the Baltic Exhibition in Malmö in 1914, Finland’s art again received a positive response even in strong Northern European competition.

Finland’s independence period

It was significant enough in the spring of 1918, when the civil war was raging in Finland, that Sallinen painted his most famous painting, “Hihuliter”, but thus his innovative power was over. The November group and Septem dissolved quickly, and the young artist’s leading artist instead became the self-taught sculptor Wäinö Aaltonen, who largely came to dominate the interwar period. In addition to this, also appeared a number of other monumental sculptors, which in particular made the 1930’s a trait of “tragicomic monument rage”. These included Yrjö Liipola, Felix Nylund, Viktor Jansson, Gunnar Finne and the animal specialist Jussi Mäntynen. The political and spiritual climate in Finland during the interwar period became increasingly nationalist, and the artists’ opportunities for form experiments were severely limited. Early on, Turku emerged as a breathing hole where Edwin Lydén was a central figure with early contacts with Klee and Kurt Schwitters and experiments in cubism, expressionism and futurism. From this period can be mentioned Wäinö Aaltonen’s collage self-portrait done in 1924. Lydén disciple Otto Mäkilä was Finland’s first surrealist, and he had international contacts. As the only Finnish he participated in the Nordic surrealist exhibition in Lund in 1937. In addition to Turku, Viborg was at that time a city from which many progressive artists came. One of these was Olli Miettinen, who during a study trip to Paris in 1931 painted cubist still life. Even more radical was Birger J. Carlstedt’s experiment with abstract art. A painter, who, like many other Finnish artists, had to go abroad through the course to be accepted in his home country, was Yrjö Saarinen who with his strong color expressionism fit better in Norway and Sweden at the end of the 1930’s. A unique development in itself at this time represents Schjerfbeck’s increasingly changed style.

After World War II, Finland’s art was again in a starting position; Reconnection to expressionism (Aimo Kanerva) and surrealism (Carlstedt, Mäkilä, Ole Kandelin) was followed by a quest for more radical new orientation, where the formation of the Prisma group in 1956 aimed to counter a narrow nationalization of art. Prism held 20 exhibitions in Scandinavia and Germany until 1970. Among the members are Sigrid Schauman, who debuted as early as 1901 but who has long been an influential critic. Now she painted landscapes and nude studies in a light flickering color play that tended toward abstract expressionism. Other members were Ragnar Ekelund, Gösta Diehl and Sam Vanni (until 1941 Besprosvanni). About 1960, the art of Finland linked again to the modern international style development, inspired by the exhibition ARS 61 in Helsinki and by the Biennals from 1960. Informalism made a rapid victory and redeemed many artists into a personal style, such as Reidar Särestöniemi. In the 1960’s, the group of Martians (fi. Maaliskuulaiset) exhibited their works. In the group, the sculptors also played prominent roles. For the sculpture, the wrestling took place with the old one between 1960, when the Mannerheim monument in Helsinki was completed by Aimo Tukiainen, and in 1962, when Eila Hiltunen was allowed to perform the Sibelius monument. Experimental artists include Laila Pullinen and Harry Kivijärvi, who abandoned the realism of a more abstract monumental style. The wood is the favorite material for the low-key lyricist Kain Tapper and the more big-voiced lumberjack designer Mauno Hartman. Difficult visionary is Carl-Gustaf Lilius, a cartoonist,

New Surrealism and pop art greatly influenced Finland’s art during the extremely pluralistic 1960’s, when a number of graphic artists such as Simo Hannula and Pentti Kaskipuro broadened the art field. Under the impression of the events of the time (the Vietnam War, the crushing of the Prague Spring) there was a lot of dedicated art. Heikki W. Virolainen newly designed well-known Kalevala characters. The culmination of freedom was reached in 1969 when Harro Koskinen from Turku was prosecuted for some paraphrases on crucifix and national arms. Kimmo Kaivanto, first prominent informalist, then engaged realist, exhibits great breadth as a graphic artist, painter and sculptor. The period also brought a boost to constructivism, where predecessors such as Carlstedt and Lars-Gunnar Nordström received well-deserved restoration. Vanni soon switched to kinetic means of expression (movement elements in the works). Experimental art gained a vital forum in the Dimensio group with, among other things, Osmo Valtonen. In the 1970’s, realism – even with social connection – was sometimes popular. New movements, such as conceptual and concept art, got practitioners in Finland through the group Harvesters (Finnish Elonkorjaajat) with JO Mallander and Olli Lyytikäinen as the main figures.

Since the end of the 20th century, art in Finland has been strongly linked to the ever-changing international art scene. A major trend in the 1980’s was the expressive painting, with Marjatta Tapiola (born 1951) and Marianna Uutinen (born 1961) as leading representatives.

Among artists in the 2000’s who work with photography and video art are Ulla Jokisalo (born 1955), Jyrki Parantainen (born 1962), Elina Brotherus (born 1972) and Eija-Liisa Ahtila (born 1959).

Since 1993, the annual Mänttä visual arts festival has been organized, focusing on contemporary Finnish art.

Crafts

The Finnish craftsmanship showed a strong style retardation in ancient times. Only a few objects have been preserved from the Vasatiden, mainly church inventory. In profane environments, chairs were rare even in the 17th century; Among baroque furniture of domestic manufacture – a large part was imported from Sweden – there are some simplified Hamburg-type cabinets. Under Karl XIIMany of the country’s mansions were destroyed during the war, and with them their homes. After a period of recovery, in the latter half of the 18th century, some flourishing occurred, but still with the support of Swedish imports. National features were therefore not lacking, among other things. under rococo, they had a preference for painted furniture in vibrant colors. After the divorce from Sweden in 1809, the Russian influence came to dominate with heavy, compact empire furniture in mahogany or birch; they were bought extensively directly from Saint Petersburg. An example of this import is the furniture in Fredrika and Johan Ludvig Runeberg’s home in Porvoo, a wedding gift by Fredrika’s parents in 1831.

Of the other branches of the arts and crafts, textile art has the oldest ancestry. Thus, to Duke Johan’s magnificent court posture at Turku Castle in 1566–73, there was also a weave jelly, which subsequently benefited Finnish rye and double-weave art.

However, it was not until the 20th century that Finnish form culture became fully applicable. For the ceramics, AW Finch’s efforts at the company Iris in Porvoo 1897–1902 and his teaching at the Central School of Arts and Crafts 1902–30 played an important role, as did later Arabia’s studio for ceramic experiments and free artistic creation with names such as Birger Kaipiainen, Friedl Holzer-Kjellberg, Toini Muona and Kyllikki Salmenhaara. In the art of furniture, Alvar Aalto, with its curved wooden furniture, has given the country international reputation, as have Ilmari Tapiovaara, Antti Nurmesniemi and Yrjö Kukkapuro. In the art of glass, Gunnel Nyman, Kaj Franck, Timo Sarpaneva and Tapio Wirkkala, the latter three also working in other areas, had special significance, within the textile arts ryya artists such as Uhra Simberg-Ehrström and Kirsti Ilvessalo and Dora Jung with compositions in linen damask. One of the foremost contemporary textile artists is Kirsti Rantanen. From around the 1960’s to the 1980’s, companies such as Marimekko and Vuokko reached world renown with their printed fabrics for fashion and interior design. As a whole, the modern Finnish craftsmanship is characterized by strict form will and shallow exclusivity – a happy symbiosis between bark bread and diamonds, which makes it unique in the world.

Architecture

Prehistoric and Middle Ages

The oldest types of housing in Finland are the open hearth and the roof that gathers heat from a log fire. In historical times these were still used as temporary housing. From the time of the migration, the knot timbre spread from east and southeast to Finland. The smokehouse or smokehouse of logs came into use during the early Middle Ages. More advanced forms of construction, e.g. timber-framed courtyards, loft sheds and two-room homes, also existed in the Middle Ages, although they were not common among the common people until the 18th century. About 75 stone churches from the Middle Ages are preserved. The first ones were built in the 13th century. They were built in shell wall technology of more or less irregular, chipped boulders. With the exception of Turku Cathedral and Hattula Church (1400’s), bricks were only used for arching and finer details. Gotlandic influence can be traced in some bipartisan Åland churches with natural stone arches. Late medieval churches in the country’s southern parts have decorated bricks that reveal a connection with architecture south of the Baltic Sea. With the walled churches as patterns, in the 15th century a wooden church architecture was developed, which in the western parts of the country until the 18th century continued the medieval long church’s traditional traditions with pillars, wooden arches and Gothic spiers. During the Middle Ages several large castles were built. In the latter part of the 13th century, Tavastehus and Turku were built as camp castles with ring walls and towers. During the earlier part of the 1400’s, the building condition of the German Knights Order also affected the castle architecture. In Turku Castle, arches were made according to patterns from the order architecture. In the 1470’s, a wall was erected around the city of Viborg.

The Vasatid and Carolinian times

As Duke of Finland, Johan III introducedin the 1560’s renaissance ideas in architecture and in housing condition through its reconstruction of Turku Castle. During the Vasatiden new fortification facilities were built in Viborg, Turku and Tavastehus. roundabouts intended for cannons. The Renaissance’s teachings in urban building art influenced the city plans that were compiled during the early part of the 17th century for both newly constructed and older cities. Distinctive features were street grids in grid designs, regular site installations, blocks and plots, as well as a quest for the symmetry of the ideal city plans. In practice, the cities that were then built became much less regular than the ideal. The building materials in the cities were almost exclusively wood. The mansions were mostly erected in wood and therefore have not been preserved, but the hallmark of them must have been the parish floor plan and the manor roof, sometimes even the French Renaissance castles dividing the building into lengths and pavilions. Two stone castles from the time of the Great Power have been preserved, Villnäs near Turku and Sarvlax east of Helsinki in Uusimaa. Only a few stone churches were erected during this time. In the Carolinian era, wooden cross churches began to be built. The clock stacks used Renaissance forms such as curved roofs and onion domes. Both the Church of the Cross and the Renaissance Pile were widely spread during the 18th century, and they are found in local varieties. The clock stacks used Renaissance forms such as curved roofs and onion domes. Both the Church of the Cross and the Renaissance Pile were widely spread during the 18th century, and they are found in local varieties. The clock stacks used Renaissance forms such as curved roofs and onion domes. Both the Church of the Cross and the Renaissance Pile were widely spread during the 18th century, and they are found in local varieties.

Freedom and Gustavian times

Following the peace in Nystad, a new border fortress, the city of Fredrikshamn, was erected, which is erected according to the plan of fortification for pattern cities as an octagonal radial city surrounded by earthen walls. The year 1748 was started under the leadership of Augustin Ehrenswaard, extensive fortification work in Helsinki and at the eastern border. The depot fortress Sveaborg, with its irregular defense works, is an original application of the principles of classical fortification doctrine. Ehrensvärd’s plans included a number of site facilities, of which Stora Borggården on Vargö (1751–53) was completed. Characteristic are the bright plaster surfaces and the banded rustic as well as the black painted iron plate on the mansard roof or the low saddle roof. Among other things, Through Carl Wijnblad’s pattern drawings, the style spread to mansions, mills and rectangles as well as to the town halls and courtyards. In most cases, bricks and plaster were replaced by logs and vertical board linings and the roof plate by boards. The main buildings of the former Gustavian classicism are the former court house (1780–87) in old Vaasa by CF Adelcrantz (now Korsholm church) and Svartå mill in western Uusimaa (CF Schröder and Erik Palmstedt, 1792). The late Stavian neo-antiquity is represented by Jacob Rijf’s churches in Ostrobothnia and LJ Desprez’s pantheon-like church (1788–95) in Tavastehus. In the south-western part of the country, which belonged to Russia (Viborgska government), classical Greek Orthodox churches were built. Fortress construction, where Alexander Suvorov was active in the 1790’s, also had a prominent position here. the court house (1780–87) in old Vaasa by CF Adelcrantz (present Korsholm church) and Svartå mill in western Nyland (CF Schröder and Erik Palmstedt, 1792). The late Stavian neo-antiquity is represented by Jacob Rijf’s churches in Ostrobothnia and LJ Desprez’s pantheonical church (1788–95) in Tavastehus. In the south-western part of the country, which belonged to Russia (Viborgska government), classical Greek Orthodox churches were built. Fortress construction, where Alexander Suvorov was active in the 1790’s, also had a prominent position here. the court house (1780–87) in old Vaasa by CF Adelcrantz (present Korsholm church) and Svartå mill in western Nyland (CF Schröder and Erik Palmstedt, 1792). The late Stavian neo-antiquity is represented by Jacob Rijf’s churches in Ostrobothnia and LJ Desprez’s pantheon-like church (1788–95) in Tavastehus. In the south-western part of the country, which belonged to Russia (Viborgska government), classical Greek Orthodox churches were built. Fortress construction, where Alexander Suvorov was active in the 1790’s, also had a prominent position here. In the south-western part of the country, which belonged to Russia (Viborgska government), classical Greek Orthodox churches were built. Fortress construction, where Alexander Suvorov was active in the 1790’s, also had a prominent position here. In the south-western part of the country, which belonged to Russia (Viborgska government), classical Greek Orthodox churches were built. Fortress construction, where Alexander Suvorov was active in the 1790’s, also had a prominent position here.

Empire

In 1811, Finland was given its own building management, the Office of the Curator, with Charles Bassi as its head. CL Engel was entrusted with the architectural management of Helsinki’s redevelopment to the capital according to a city plan by JA Ehrenström. Engel’s main work is the Senate Square in Helsinki (1818–52) with surrounding buildings. English’s neo-classical style is a variation of the empiricism of St. Petersburg, and most public buildings are of plastered bricks and yellow painted. As head of the Office of the Deputy Governor after Bassi, Engel, with the help of his assistants (AF Granstedt, Jean Wik and AW Arppe), was able to influence the architecture throughout the country. Engel designed city plans including for cities that need to be rebuilt after devastating fires (Oulu, Turku, Tavastehus). He created a city type that was characterized by wide streets laid out in grid pattern, fire alleys and sparsely built plots with one-story wooden houses and plantings. The churches of the district office were characterized by the central church tradition. They were often made of wood with considerable dimensions, e.g. Kerimäki (AF Granstedt). The anonymous architecture of the countryside was also influenced by neoclassicalism.

The latter part of the 19th century

The business area of the Office of the Deputy (from 1865 the Supreme Board of Public Buildings) grew with the need for institutional buildings such as schools, prisons, town halls etc. EB Lohrmann introduced an ascetic arch style in the state architecture and in the church architecture became the long church, often in brick and with Roman or Gothic details. prevailing type. The Old Testament Chiewitz applied light wood structures, cast iron structures and bricks in industrial buildings and churches. For the new Vasa, Carl Axel Setterberg drew the city plan, public buildings and private housing. Setterberg’s court and churches in Vaasa and Chiewitz Riddarhus (1860–62) in Helsinki are examples of the medieval inspired style of eclecticism. Already in the 1880’s, architecture became noticeably more standardized. In state institution buildings, uniformity and type thinking increased. For schools, a special type was prepared, the cell prison was introduced about 1870 and the railway administration divided the type drawings for the station houses into different classes. The larger hospitals were built according to the pavilion system. The most important municipal building was the City Hall, preferably with a luxurious banquet hall and parade stairs, eg. in Vaasa (Magnus Isaeus, 1878) and in Tampere (Georg Schreck, 1890). The first malls were built in Helsinki and Turku (G. Nyström, 1889 and 1891, respectively). The industrial buildings were influenced by the international industrial architecture and were sometimes designed by foreign experts. Larger facilities were built in brick, e.g. the rapids area’s factories in Tampere, the paper mill in Nokia, Verla wood grinding and Sinebrychoff’s brewery in Helsinki.

The continental metropolitan architecture gained a foothold, especially in the capital. Residential houses in 3–5 floors with shops at ground level began to characterize entire blocks and street streets. Around 1890 it became common to plan special apartments for business offices, banks and insurance companies. In the 1870’s, the facade details were usually made with brick masonry and plaster. The decor became richer in the 1880’s, and stucco ornaments became commonplace. The design language was usually a free application of the Renaissance, either classically or with elements of medieval style elements. In order to achieve greater freedom in the design of retail premises, bank expeditions, restaurants and similar spaces, iron structures began to be used in the multi-storey buildings as well. For larger institutional buildings, appliances for central heating and air exchange were installed.

The foremost architects of the 1870’s and 1880’s were Frans Sjöström and Theodor Höijer. Sjöström was more classic than Höijer, but both were influenced by currents that wanted to reconcile medieval features with the rich ornament of the Renaissance. Towards the end of the 1880’s, a criticism of the former eclectic flow arose, and they began to demand a strictly classifying form as well as more pure applications of historical styles. Gustaf Nyström and Sebastian Gripenberg, senior director of the Supreme Board of Public Buildings, were representatives of the movement. Ständerhuset (1890) and the National Archives (1886–90) are two examples of Nyström’s classicism. The design language was intended to fit the new buildings into the cityscape created by Engel. The architecture of the large public buildings is characterized by iron structures, which by e.g. Höijer in the Ateneum (1885–87) was used to dissolve the closed effect by means of arcades and columns. The rationalist Nyström’s iron constructions realize the classic tectonics of architecture or fulfill completely practical purposes. Despite advances in construction technology, the inexpensive timber remained the most popular building material. Changing styles and the increased industrial treatment of the construction work contributed to a changed street image. Wood was also used to erect larger public buildings, such as churches, schools and fire stations. Changing styles and the increased industrial treatment of the construction work contributed to a changed street image. Wood was also used to erect larger public buildings, such as churches, schools and fire stations. Changing styles and the increased industrial treatment of the construction work contributed to a changed street image. Wood was also used to erect larger public buildings, such as churches, schools and fire stations.

1900’s and 2000’s

The renewal process around 1900 began in Finland as well as in other countries in protest of the classical tradition. The international Art Nouveau style received a strong national interpretation. However, the hallmarks of national romance, asymmetry and expressive forms in stone and timber construction, were often innovations that could not be attributed to a true national tradition. The classical ornament was replaced with bears, squirrels and conifers carved in stone; great emphasis was placed on the craft. Main moments from this time are Tampere Cathedral (Lars Sonck, 1906) and the artist villa Hvitträsk (Herman Gesellius, Armas Lindgren and Eliel Saarinen, 1903).

National romance had a cool but short flowering 1897-1905. Increasing criticism, which got its culmination in Sigurd Frosterus and Gustaf Strengell’s famous pamphlet from 1904, forced the romantics back into discrete forms and symmetry. In the shadow of national romance, there was an internationally embraced rationalism with Selim A. Lindqvist as the main representative. The Saarinen station house in Helsinki (1904-14) can be seen as a happy synthesis of the contradictory endeavors of the entire Art Nouveau period.

Around 1920, the time was ripe for a return to classical forms in the sign of Scandinavian classicism. The new generation with Alvar Aalto, Erik Bryggman, Pauli Blomstedt and Hilding Ekelund at the forefront made strong impressions, especially of the Swedish architect Gunnar Asplund. The most Finnish work during the 1920’s is Kottby Garden City in Helsinki (Martti Välikangas 1920–25). There, the true indigenous tradition is found in the rectilinearness of the city plan, in the timber construction and board lining of the buildings, as well as in color. The area reflects the social consciousness that can be seen as a result of the civil war of 1917-18. Its monumental counterpart is the Parliament House designed by JS Sirén (1924–31).

In the form of functionalism, international modernism was given a more powerful “heroic” interpretation than in the other Nordic countries. Alvar Aalto’s sanatorium in Pemar (1929–32) opened the way to international recognition. Asplund was again the guide, but the Finnish architects were also in direct contact with continental pioneers such as Le Corbusier and Walter Gropius. Functionalism had a short flowering, but also broke through in traditional assignments such as churches, for example. Blomstedt Church in Kannonkoski (1938). Towards the end of the 1930’s, the architecture began to have more national features and softened up with, among other things. richer use of wood as material.

This voluntary return to traditional building methods proved to be an unconscious preparation for the simple architecture of the 1940’s, the war decade. The main emphasis was now placed on wooden houses, which were also partly designed by prominent architects. The 1940’s can be seen as a necessary respite, an antithesis to functionalism. When a return to functionalism occurred in the early 1950’s, architecture was able to show greater wealth and local connection than was the case during the 1930’s. Most striking was Aalto’s architecture in red brick and a richly articulated design world. The most well-known example from this period is the small municipal building in Säynätsalo from 1952. Aalto’s humanism received as an antipole an internationally embedded rationalism with Viljo Revell as the main representative.