Literature

From land name time to about 1200

The Norwegian settlers who set course for Iceland from the end of the 8th century brought home a rich flora of traditions and memories. A large part of these were fairy tales, ie. stories of both historical and fictional nature; an important feature was the goddess and hero songs of eddapoes. In Iceland, too, from the very beginning the difficult “sports” of the named skalds were often recognized, often killing kings and other rulers, so-called Herd poetry. All this was originally transmitted orally.

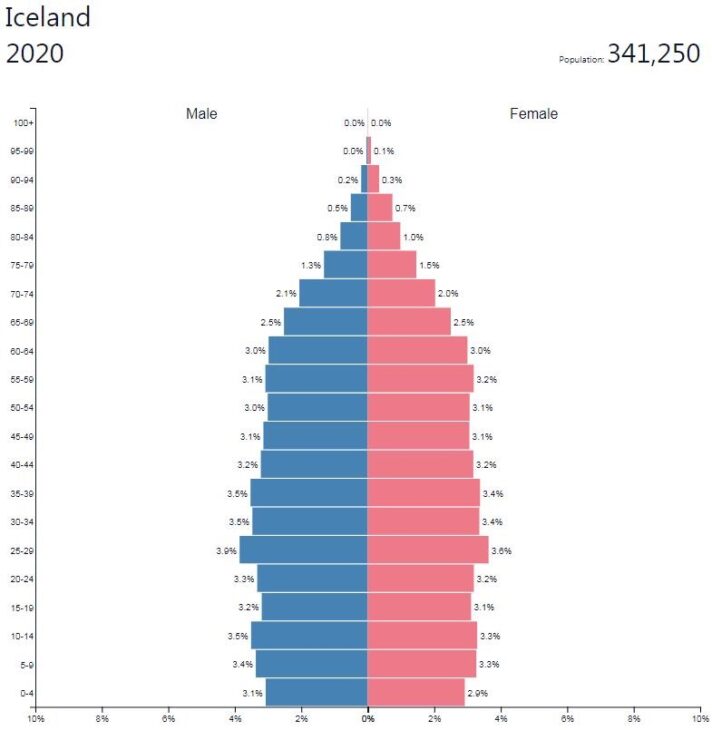

- Countryaah: Population and demographics of Iceland, including population pyramid, density map, projection, data, and distribution.

With the introduction of Christianity around the year 1000 and the contact with the Church of Europe, the writing arts developed and led to an increasingly lively authoring activity. Iceland’s first history writer was Sæmundr Sigfússon, as far as you know the first Nordic resident to receive his education in Paris. His now lost work, which was certainly written in Latin, was by all accounts a chronicle of the Norwegian kings, at the same time noting the most important events in Iceland.

Around 1100 Icelandic people began to use recordings. The so-called first grammatical thesis, which usually dates to about 1150, in itself a strangely clear-cut test of early Icelandic linguistics, mentions in particular laws, genealogical records, explanations of Christian beliefs and “the teaching that Ari Thorgilsson recorded with insightful understanding” – ie. Are Frode’s historical works. Preserved is his “Íslendingabók”, a very brief Icelandic history from the time of the country until about 1120. Possibly Are also had his hand in “Landnámabók”. There, about 400 of the most important land names (settlers) are reported, their origin, where they settled and their descendants.

1200’s

The truly great century in medieval Icelandic literature was the 13th century. Not least then, with the spread throughout the century, those who genre unique Icelandic sagas (genealogies, genealogies) were added. There were anonymous texts with highlights such as “Egill Skalla-Grímsson’s saga”, “Laxdœla saga”, “Eyrbyggja saga”, “Njal saga” and “Grettes saga”. With their realism and elements of sharp-cut dialogue, they constitute a classic epic of timeless kind. They take place essentially during the hundred years from the establishment of the Alliance 930 to 1030, the stage that is usually called the saga.

Stylistically related to the Icelandic sagas are the ancient age sagas (ancient tales), about the time before the land take. They often have a more mythical character with giants, dwarfs and fabulous animals in the scenario.

Towards the end of the 1100’s there were stories about the mission kings Olav Tryggvason and Olav Haraldsson (“Holy Olav”). A great biography of King Sverre was written by the abbot Karl Jónsson. The stage’s all-too-dark literary figure, also a politically strongly engaged stormman, was Snorre Sturlasson. With his Edda from the beginning of the 1220’s he laid the still indispensable basis for the study of Norse mythology and Icelandic poetry. Thanks to this poet’s textbook, many examples of both the anonymous eddy poetry and the names of the named skald have been preserved. But Snorre’s great work is “Heimskringla”, the chronicle of the history of the Norwegian kings and earls from the earliest times to King Sverre.

A powerful documentation of the troubled stage of the Sturlunga period is the person-grinding “Sturlunga saga” (c. 1300), where a number of different authors portray Iceland’s history during the 1100’s and 1200’s until 1262-64. A major part of the work was written by Snorre’s nephew Sturla Thórðarson, himself a participant in and witness to many of the episodes he portrays. He was also given the confidence to sign King Håkon Håkonsson’s story and thereby set the mark for the remarkable era of the Northwestern history writing.

1300 to the Reformation

The new century led to a harvest of “post-classic” Icelandic sagas. The 13th century was otherwise a time of compilation and anthologies of older texts. Important such manuscripts are “Möðruvallabók”, “Vatnshyrna” and “Flateyjarbók”, with many Icelandic and royal sagas.

During the 1300’s, Icelandic poetry in the tradition of oath and shell poetry had largely ebbed out. However, some Christian poems provide a test of faithfulness to the ancient poetic language. “Sólarljóð” (“The Sun Song”), possibly from the 13th century, is a suggestive vision poem in the form of eddapoe poetry (ljóðaháttr), where Norse mythology peculiarly violates a strictly Christian spirit. The big plant is “Lilja”, which usually dates to the middle of the 1300’s. There is a regular drapa to God, Christ and the Virgin Mary – 100 stanzas of a rich dróttkvætt -versmått with an ingenious construction.

However, during the 1300’s a new form of profane epic poetry, rímur (ríma), emerged, which preserved much of the peculiarities of the northern poem in language and style, for example. kennings. The subjects of these elaborate songs were gladly taken from the peculiar world of the ancient age sagas. The rhymes became popular and, with their strict formal requirements, had a significant part in the unique continuity of Icelandic poetry from ancient to present.

From the Reformation to 1800

In 1550, Iceland’s last Catholic bishop, Jón Arason, decapitated, who had fiercely opposed the Reformation ordered from Denmark. An important literary task now became the Bible translation, which with the New Testament (1540) became the first ever preserved printed Icelandic book; the whole work was in 1584.

Religious poetry reached a climax with Hallgrímur Pétursson’s “Passion Psalms” (“Passion Psalms”), in which he meditates for fifty psalms on the sufferings and salvation of Christ. With this work, first printed in 1666 and then in over sixty editions and many translations, he appears as one of the Nordic countries’ foremost poet poets. A time-honored document is Priest Jón Magnusson’s “Píslarsaltari” (“History of Suffering”), which was first published today. It is an eerie testimony of persecution mania in the witches’ era, written with a monomaniacal intensity that has been compared to Strindberg’s.

Around 1600, interest in the saga era came to life throughout the Nordic region. Old Icelandic manuscripts were collected, interpreted and processed. Arngrímur Jónsson, with his writings in Latin on ancient Iceland, reached out to the European scientific world. An excellent significance for the Northern study became the official Árni Magnússon, professor in Copenhagen. With his devoted search for Icelandic manuscripts, he created the collection called the Arnamagnæanska. It has long been a center for research in Northern literature.

A naturalist and poet from the epoch of enlightenment and utilism was Eggert Ólafsson. His best-known poem, “Búnadarbálkur” (“Agricultural bar”), is a tribute in physiocratic spirit to the Icelandic ideal farmer. As well as an employee, Ólafsson traveled around the country and then wrote in Danish “Reise igienem Island” (1772), which in its versatility is reminiscent of Linnaeus’ Swedish travelogues.

From 1800 until the First World War

At the beginning of the 19th century, in the circle of Icelandic intellectuals in Copenhagen, the impression was made of the romantic flow on the continent as well as of the political freedom movements of the time. Now a more unified and determined struggle for national independence began, led by historian and politician Jón Sigurðsson. Around the journal Fjölnir (from 1835) gathered young Icelanders who dreamed of a national revival, a new heyday in the spirit of the fathers. Among them, naturalist Jónas Hallgrímsson was the leading bald, one of Iceland’s largest. He made a sharp settlement with the long-held hegemony of the rhymes. Against the background of their traditional rigidity, his own poetry of nature and love emerged with a whole new immediacy. His older contemporary, Bjarni Thorarensen, poured his fatherland poems into the forms of ancient Edda poetry.

With his public life portrayals, Jón Thoroddsen became the pioneer of the Icelandic novel. His work, which reveals the influence of Scott and Dickens, has its strength in environmental depiction and colorful bifurcations. During the latter part of the 19th century Matthías Jochumsson achieved a position as one of Iceland’s poeta laureatus. Among his many memorial poems and hymns are the Icelandic national anthem, “O God of our Land”.

A representative of the social-critical prose of the late 19th century was Gestur Pálsson, who posed problems during debate in Brandes’ spirit and hostages to abuse of power and hypocrisy. Compassion with the small and oppressed also characterizes Einar Kvaran’s stories.

Among many writers with deep roots in Icelandic public life are Guðmundur Friðjónsson. During his entire life as a farmer, he wrote a number of poetry collections and prose works and participated extensively in contemporary literary debate.

A lyricist of the same generation was Thorsteinn Erlingsson, whose poetry along with nature and love poems contain radical attacks on worldly and spiritual authority. Emigrant Stephan G. Stephansson, during a tiring existence as farmers in the United States and Canada, made weighty efforts with lucid thought poetry.

One bald of the large format was the colorful lawyer Einar Benediktsson. His poetry is characterized by bold antitheses and suggestive imagery. They give the far-sighted view of the white travels and not least the visions of a great Icelandic future.

To reach a larger readership, some Icelandic writers started writing in the language of the Union country of Denmark: Gunnar Gunnarsson, Guðmundur Kamban and Jóhann Sigurjónsson. They were all born in the 1880’s and debuted in Danish over the years around the outbreak of the First World War. Gunnarsson, with his powerful storytelling art, gained a large audience, not least in Germany. Sigurjónsson’s luck throw was the play “Bjærg-Ejvind og his Wife” (see Drama and theater below). The younger Kristmann Guðmundsson won a position with short stories and novels in Norwegian, before returning to his native country and native language in 1938, as well as his compatriot Gunnarsson.

Mellankrigstiden

At the time of the end of the First World War, Icelandic poetry emerged with new subjects and forms. The ice was broken by Stefán Sigurðsson from Hvítadal, but a wider register showed Davíð Stefánsson in his smooth excuse. Tómas Guðmundsson’s is characterized by light touch and impressionistic style. In the 1930’s, Jóhannes Jónasson from Kötlum joined the radical socialist falcon around the magazine Rauðir penn (red pennas) and wrote flaming revolutionary poetry.

A key figure in the 20th century prose poetry was Thórbergur Thórðarson. In his original association of radicalism and personal bizarre, he became a guide to a more liberated prose art. Among the younger ones who made an impression was Halldór Laxness, who with rich artistic exchange played out Icelandic tradition towards international civilization and modern ideologies. His long career in writing went from social criticism to an ever deeper acceptance of Icelandic heritage – an effort that was rewarded with the 1955 Nobel Prize. A storyteller of more traditional incision was Guðmundur Hagalín, who portrayed core people and originals from his hometown of the West Fjords.

Republic

The proclamation of Iceland as a republic in 1944 also provided a powerful stimulus for literature. The end of the war brought a number of new international contacts and impulses. But the continued presence of the US armed forces in Iceland, in the name of NATO, for decades remained a moment of irritation often expressed in the poem. The rapid depopulation of the sparsely populated area was also a social problem that was dealt with in the prose of the time.

Guðmundur Daníelsson aroused interest with compelling public life depictions from his hometown in Hekla’s neighborhood. A nice stylist with nuanced character drawing was Ólafur Jóhann Sigurðsson. In a trilogy, Indrei G. Thorsteinsson gave a penetrating picture of 1930’s depression in Iceland. Notable female writers include Jakobína Sigurðardóttir, who has an accurate psychology of everyday life, and Svava Jakobsdóttir, who has written short stories and novels with an emphasis on female experiences.

An internationally oriented modernist is Thor Vilhjálmsson, a meticulous style artist who likes to have his stories played out in southern European environments. A lush, absurd technique, with realism and surrealism combined, has been developed by Guðbergur Bergsson.

The renewal has been noticeable, not least in the lyric, where the contrast with traditional Icelandic versatility is most noticeable. However, Snorri Hjartarson’s finely tuned reflection poetry is marked less by refraction with the old than by refinement on an older foundation. Steinn Steinarr is the leading poet of the stage. His scarce and often bitterly aphoristic poems have elements of mysticism and developed into a subtle play of form and color.

A poem of a more or less modernist nature, related to, among other things, Swedish 1940’s and other related directions – what in Iceland has been called “atomic poetry” – have many high-class practitioners: Jón Jónsson from Vör, Einar Bragi Sigurðsson, Jón Óskar Ásmundsson, Hannes Sigfússon, Hannes Pétursson, Thorsteinn Jónsson frá Hamri.

The late 20th century offers a picture of great vitality. Vésteinn Luðvíksson, Pétur Gunnarsson and the slightly younger Einar Már Guðmundsson and Einar Kárason have appeared mainly as proseists. Among many new female poets, for example, Steinunn Sigurðardóttir and Frida Sigurðardóttir clearly have their own profiles. All of these writers are intensely concerned with processing their own generation’s experiences, but with great stylistic ingenuity, in many places with a “magical realism” of unmistakable Icelandic brand.

A major breakthrough, even internationally, in the 1990’s, Vigdís Grímsdóttir received her imaginative and multifaceted novels, eg. “The Girl in the Forest” (1992; “The Girl in the Forest”). Even after the turn of the millennium, Icelandic literature is characterized by great versatility with names such as the poet Sjón, the author of poetry Arnaldur Indriðason and the savvy stylist Gyrðir Elíasson, who was awarded the Nordic Council Literature Prize 2011.

Children’s and youth literature

Few books for children were published in Iceland before the 20th century. In the years 1907–08, childhood memories were published by Sigurbjörn Sveinsson, and somewhat later by Jón Sveinsson; childhood memories were a popular genre in Icelandic children’s literature. Otherwise, there were most short stories and stories. The first children’s novel came in the 1930’s (by Gunnar M. Magnuss).

Among today’s foremost writers for children and adolescents are Guðrun Helgadóttir, whose “Ástarsaga frá fjöllorna” (1981; “The Story of Flumbra”), with pictures by Brian Pilkington, has been translated into several languages. Kristín Steinsdóttir’s picture book “Engill í vesturbænum” (2002; “The Angel in the Staircase”) was also a great success and was awarded the Nordic Children’s Book Prize in 2003.

Drama and theater

Safe tests of Icelandic drama can be found first at the cathedral school in Skálholt during the latter part of the 18th century, and then in the modest form of the school drama, most with an educational purpose. In the 19th century, the growing Reykjavík took the lead, when, under the auspices of the upper secondary school, plays were given by Molière and Holberg. A decisive effort was made by the versatile artist Sigurður Guðmundsson (1833–74)), which gave Shakespeare a place in Icelandic performing arts. He himself wrote many plays and inspired his countrymen to take up subjects from Icelandic folklore, such as Shakespeare translator Matthías Jochumsson’s “Útilegumennirnir” (“The outlaws”, 1862; revised version under the title “Skugga-Sveinn”, 1898) and Indrei Einarsson’s The New Year’s Night ”(‘New Year’s Night’, 1871). An international breakthrough for Icelandic drama was Jóhann Sigurjónsson’s “Fjalla-Eyvindur” (1912; publisher in Danish 1911, “Bjærg-Ejvind and his wife”), which was filmed in 1918 under the direction of Victor Sjöström. Guðmundur Kamban also wrote plays in the national spirit, but also examined the modern judiciary, among other things. in “We Murderers” (1920; in Danish).

Reykjavik’s theater company has had its own stage since 1897, and in 1950 the Thjóðleikhúsið (National Theater) was completed. A four-year state theater school was established in 1975, and in 1989 a new functional city theater was opened in Reykjavík. Outside the capital, in Akureyri, there is a professional theater ensemble. The exchange with foreign directors and ensembles has long been lively and mutual. There are about sixty amateur theater groups in the country, and the larger theaters often tour the country. Icelandic theater now has an annual audience frequency of about 400,000 spectators. The main attraction is the domestic repertoire with Laxness in the center. Among later playwrights is Agnar Thordarson (born 1917) and especially Jökull Jakobsson (1933–78). Domestic drama continues to claim its central place alongside the foreign repertoire at the major theaters and new dramas are constantly emerging. Vigdís Grímsdóttir has also played abroad.

Film

Co-productions with other countries in the filmization of famous fairy tales or modern literary works, such as the Swedish-Icelandic “Salka Valka” (1954) based on Laxness’s novel, dominate the Icelandic film history. The start of Icelandic television in 1966 and especially the formation of the Icelandic Film Fund in 1979 created the conditions for a continuous film production.

The link to domestic literature and the myth tradition has remained strong, while the lack of film education in the country has contributed to many international influences. The latter is illustrated by Hrafn Gunnlaugsson’s Viking sagas, Sweden-trained Hrafn Gunnlaugsson (1984) and “The White Viking” (1991). Other well-known directors who broke through in the 1980’s are Ágúst Guðmundsson (born 1947; “Land and Sons”, 1980), Thorsteinn Jónsson (born 1946; “… and then they become great”, 1981) and Ari Kristinsson (born 1951; “Passport for Me”, 1997).

Since the early 1990’s, Friðrik Thór Friðriksson has been Iceland’s most significant producer and director, among others. with the Oscar-nominated “Children of Nature” (1991), “Devil’s Island” (1996), “Angels of the Universe” (2000) and “Mamma Gógó” (2010).

Internationally more notable names in recent years are the actor and director Baltasar Kormakúr (born 1966), who has done, among other things. “101 Reykjavik” (2000), a 2006 filmization of Arnaldur Indriðason’s best-selling crime novel “Glasbruket” (2000) and American “Contraband” (2012), director Dagur Kári (born 1973) with “Nói Albinói” (2003), “Dark Horse “(2005) and” The Good Heart “(2009), and director Baldvin Zophoníasson (born 1978) with the festival-acclaimed” Jitters “(2010) and” Life in a Fishbowl “(2014).

Art

THE MIDDLE AGES

Compared to literature, medieval art in Iceland is of little scope. It consists mainly of wood carving art and book painting, but according to written sources, there were also murals in some of the now lost medieval churches. At the beginning of the Middle Ages, the Icelandic woodcarving art stood at a very high level and was related to that developed in the Norwegian stave church architecture during the 11th and 11th centuries. It manifested itself in ornaments with roots in the Viking Age art and images carved or carved in wooden planks. Such planks have been preserved in a relatively large number from both church and profane buildings and are now stored at the National Museum (Thjóðminjasafn Íslands) in Reykjavík. Notable include the planks from Flatatunga and Bjarnastadahlíd whose carvings show parts of a large and Byzantine-inspired representation of the ultimate judgment. Also famous is the Romanesque church door from Valthjófsstaður with a carved representation of the legend of the knight who received a lion to accompany.

The book painting is younger and had its heyday during the 1300’s. However, from the time around 1200, there are two illuminated manuscripts by Physiologus. The images in them are characterized by influences from England, and that style orientation continued for the following centuries. Among the illuminated manuscripts from the 1300’s are mainly the Board, which contains an Icelandic translation of the Old Testament, and the Flatöboken (Flateyarbók), which is a collection manuscript of kings, poems and annals.

A special category belongs to the so-called Icelandic sketchbook from the 1400’s. It is unique in the Nordic countries but adheres to European manuscripts with cartoon images of various kinds. It comprises 21 parchment leaves that are covered with drawings, many of which are made from considerably older models.

20th century outdoor painting and symbolism

Icelandic visual art was resurrected in the early 1900’s, when artists trained in Copenhagen in the 1890’s returned to Iceland to devote themselves to free art creation there. The three pioneers, the sculptor Einar Jónsson and the painters Thórarinn B. Thorláksson and Ásgrímur Jónsson, took the impression of romantic naturalism, which was well in tune with the national feeling of the time in Iceland. However, Einar Jónsson left naturalism for symbolism early on and created an idea art based on theosophy. The two mentioned painters devoted themselves to outdoor painting with the Icelandic nature as motif, and with Ásgrímur Jónsson as the foremost pioneer, the landscape became increasingly important in Icelandic visual art. The painters Jóhannes Sveinsson Kjarval and Jón Stefánsson introduced a non-naturalistic concept of art in Icelandic landscape art. Of them, Kjarval was the original landscape interpreter; in his magnificent paintings he created a synthesis of deep natural experience and impressions of both symbolism and modernism.

Modernism

As a student of Matisse and an interpreter of Cézanne’s art, Jón Stefánsson became the main representative of a modernist conception of art in the maturing Icelandic visual art during the 1920’s. He came to exert a strong influence on both the contemporary and the next generation of Icelandic artists. A radical feature was Finnur Jónsson’s cubist and non-figurative works from his studies in the 1920’s in Germany. His experiment, however, did not directly follow in Iceland, and 1930’s art came to be characterized by low-level expressionism and Late Cubism. The sculptor Ásmundur Sveinsson appeared with monumental sculptures of working men and women, and the painters derived motifs from people’s everyday lives. The sculptor Sigurjón Ólafsson and the painter Svavar Guðnason participated in the activities of radical artists in Denmark before and during the Second World War. Sigurjón Ólafsson took the impression of surrealism and participated in, among other things. in the Linien international exhibition in 1937, while Svavar Guðnason was active in magazine Helhesten and contributed to the development of an abstract expressionist visual art. Guðnason’s exhibition in Reykjavík in 1945 paved the way for new impulses in Icelandic art and resulted in the formation of the September group, whose exhibitions became a forum for the radical and non-performing arts that emerged around 1950. The concrete art gained a strong position in the 1950’s. with Thorvaldur Skúlason as the main representative. A more lyrical expressionism was expressed by Nina Tryggvadóttir,

In the 1960’s, a new generation of artists emerged who reacted to the dominance of abstract art. The now internationally known artist Erró, who left the country as early as the 1950’s, took the impetus from surrealism into the creation of a figurative art. Other artists in the younger generation got in touch with and were influenced by, among other things. Fluxus, neodada and pop art. In 1965 the SÚM group was founded and four years later the SÚM gallery, which became something of a stepping stone for controversial and politically radical art. the concept artist Sigurður Guðmundsson, the minimalist Kristján Guðmundsson and the sculptor and performance artist Magnús Pálsson. In 1978, the Living Art Museum was founded which, in addition to being an art collection, has continued the role of the SÚM gallery as a forum for experimental art in Iceland.

The group SÚM also included Hreinn Friðfinnsson, who is still one of Iceland’s leading concept artists in the early 2000’s with his work in various techniques such as photography, drawing, sculpture, installation and text. In a similar way, Ragnar Kjartansson works, which mixes visual arts, theater and music in performance performances that last for a long time. Katrín Sigurðardóttir creates sculptural installations where the spectator himself becomes part of the work, while the painting tradition is continued by Eggert Pétursson with his extremely detailed oil paintings of plants from the Icelandic fauna.

Architecture

The oldest preserved buildings in Iceland date from the Danish monopoly trade in the 18th century. These are simple, prefabricated single-story wooden houses imported to Iceland where they are erected at various trading venues. From the 18th century also a number of public buildings of natural stone, erected according to the drawings of Danish court builders. Among them is the dwelling house on Vidö (1752–55) by Nicolai Eigtved and Holar Cathedral (1757–63) by Laurids de Thurah.

Through Iceland’s increased political independence from Denmark in the 19th century, Reykjavík was increasingly given the role of the country’s administrative center. In Reykjavík, public buildings were erected by Danish architects, e.g. Latin School (1844-46) by Jørgen Hansen Koch and LA Winstrup’s remodeling of the cathedral (1847-48); both late-classist buildings that made their mark on the city. The construction of the Everything House (1880–81), a neo-Renaissance building in natural stone by Ferdinand Meldahl, led to a significant increase in stone house construction in the 1880’s and 1990’s. At the same time, wooden house construction experienced its heyday, especially around the turn of the century. A new building material, corrugated sheet metal, began to be used and came to give the Icelandic wooden architecture a special character.

No domestic architectural activity came into existence until the early 1900’s. In 1904, the first Icelandic architect, Rögnvaldur Ólafsson, was hired as Iceland’s newly-established Home Rule’s building consultant. Ólafsson, who was educated in Copenhagen, had taken the impression of Danish architecture from the so-called Nyroptiden and sought to create an individual architecture with roots in Nordic tradition. At the same time, he advocated a new building material, the concrete. Ólafsson was succeeded by Guðjón Samúelsson, Iceland’s first graduated architect, educated in Copenhagen. Samúelsson was superintendent 1919-50 and as such came to have great influence. His building works, e.g. the university (1940) and the national theater (1950), both in Reykjavík, are characterized by an effort to create a national style in keeping with Iceland’s building traditions and nature.

Sigurður Guðmundsson, initially a representative of the neoclassicalism of the 1920’s, later became advocates of functionalism, together with, among other things. Gunnlaugur Halldórsson. Halldórsson sought to adapt the ideas of functionalism to Icelandic conditions and succeeded in creating a consistent and uncompromising architecture.

Just before the financial crisis struck in 2008, several high-rise buildings and bank offices, mainly Reykjavík, were erected in a postmodern style that feels strange in the older buildings. In connection with the crisis, several construction projects were halted. In 2011, Reykjavik’s new concert hall and conference center Harpa, inaugurated by Henning Larsen, was inaugurated in collaboration with the Icelandic architectural firm Batteríið.

Today’s Icelandic architecture is characterized by diversity but also by a lack of domestic tradition, which can possibly be explained by the fact that Iceland’s architects now seek their education in many different countries instead of, as in the past, almost exclusively in Denmark.

Music

The poverty and isolation of Icelanders has resulted in an instrument-poor music history. The dance was banned by the Danes in the late 17th century. Besides church songs (the first hymnal with melodies printed 1589, an voluminous gradualbok 19 editions published in 1594 to 1779) were grown tvísöngur for two parallel feed on male voices quint distance and rimur, intonated hero poems the chance of the geste type.

Classical music

For the millennium anniversary of Iceland’s colonization in 1874, Matthías Jóchumsson wrote the national song “Ó Guð vors lands”, composed by the Leipzig-trained Sveinbjörn Sveinbjörnsson (1847-1927), who was the first composer to devote himself to art music. The arrival of the cathedral organ in Reykjavík in 1840 opened the country to foreign impulses. Páll Ísólfsson (1893–1974), pupil of Max Reger and assistant to Karl Straube in Leipzig, is regarded as the foremost cathedral organist, after his return celebrated for an cantat for the millennium anniversary of Alltingets millennium in 1930, later head of the music school and radio head of music.

Jón Leifs studied in Leipzig and lived in Germany until 1943, when he returned to Iceland via Sweden. In 1945 he founded the composer association Tónskáldafélag Íslands and in 1948 the copyright office STEF. During his lifetime, his quest to create an Icelandic identity in music was derided and only in 1991, in connection with the premiere of the dance drama “Baldr” (1943-48), his original tone language gained general recognition. Although not well known abroad, Leifs is today regarded as Iceland’s national composer.

Icelanders heard symphony music for the first time in 1926 at the Hamburg Philharmonic’s guest play under Jón Leif’s leadership. In 1950, Iceland Symphony Orchestra was founded, preceded by salon orchestras in Reykjavík and Akureyri. Several composers have been recruited from the symphony orchestra, such as German-born trumpeter Páll Pampichler Pálsson (born 1928) and Austrian hornist Herbert Hriberschek Ágústsson (born 1926).

The Conservatory of Music in Reykjavík was founded in 1930, and later a number of music schools have been established. Since 1947, a growing number of Icelandic musicians and composers have educated themselves in the USA, Germany and the Netherlands, and have found a home market that, despite the small population and the limited opportunities to be performed, published and recorded, is surprisingly diverse.

In 1941 the first Icelandic opera (“Á áögögum” by Sigurður Thórðarson) was given, in 1974 the first opera (“Thrymskviði” by Jón Ásgeirsson). Atli Heimir Sveinsson has had great successes including the opera “The Silk Drum” (1982), the musical “The Land of My Father” (1985) and the TV opera “Vikivaki” (1990). In 1979, the internationally acclaimed Icelandic opera was formed in Reykjavík.

An older Hindemith-Bartók-oriented composer generation is represented by Karl O. Runólfsson, Jón Thórarinsson, Jón Nordal and Magnús Blöndal Jóhansson, a more radical middle generation of, in addition to Sveinsson, the versatile Thorkell Sigurbjörnsson and his cousin Leifur Thórarinsson (1934–98). Among younger composers are Thorsteinn Hauksson (born 1949) with electronic music as a specialty, Karólína Eiríksdóttir (born 1951) with the opera “Someone I’ve Seen” for Vadstena Academy 1988, choir leader, theater composer and Leifs researchers Hjalmar H. Ragnarsson (born 1952) and Áskell Másson (born 1953) with concerts and an opera.

The choral song is widespread; The main choirs include the Polyfón Choir, led by Ingólfur Guðbrandsson (1923–2009), and the Hamrahlið Choir, led by Thorgerdur Ingólfsdóttir (born 1943).

Several foreign musicians have contributed to the renewal of music, such as the flutists Manuela Wiesler from Austria and Robert Aitken from Canada. American violinist Paul Zukofsky has founded the Icelandic Youth Orchestra, and Russian pianist Vladimir Ashkenazy started the 1968 Reykjavík Art Festival.

Since 1981, Myrkir Music Days has been organized by the composer association.

popular

Iceland’s rich folk tradition is still very much alive among the Icelandic population. Particularly strong is the tradition of epic poems, rhymes, performed by male vocalists. The Danish-Icelandic singer Engel Lund (1900–96) made a great contribution from the 1930’s to the recording and preservation of Icelandic folk songs. After the Second World War, several dance orchestras and jazz bands performed internationally, but like the rest of the world, jazz was increasingly suppressed by rock music in the late 1950’s.

A number of indigenous rock groups appeared in the 1960’s and 1970’s without attracting much attention outside the country. One of Iceland’s most famous musicians, drummer Pétur Östlund, was active in several jazz and pop groups in the 1960’s before moving to Sweden in 1971. Singer Bubbi Morthens (born 1956) became popular with the mix of rock, blues and reggae from the late 1970’s, and the 1980’s punk scene was lively with bands such as Theyr and Purrkur Pillnikk.

In the 1980’s, the jazz rock group Mezzoforte also had some success internationally and several groups within the indie rock scene began to be noted, including Sugarcubes with singer Björk. When Björk began a solo career in the 1990’s with albums such as “Debut” (1993), with influences from rock, world music and modern dance music, the greatest export success of Icelandic music of all time was created. Her distinctive voice and visual appearance have contributed to her position as one of the most original artists in today’s globalized music industry. With Björk’s popularity, the outside world caught the eye of Icelandic rock music. An international breakthrough around 2000 got the group Sígur Róswith his orchestral post rock on an album such as “Ágætis beginning” (1999). In their wake, several groups from Reykjavik’s vital music scene emerged in the early 2000’s, for example. mum, Amiina and Rökkurró and singer Hafdís Huld (born 1979).

Within today’s music scene is also noticed the group Bang Gang, which mixes melodic pop with electronica, while house and techno have influenced the group GusGus, whose singer Emíliana Torrini (born 1977) has also had a successful solo career.

Jazz singer Ragnheiður Gröndal (born 1984) is one of Iceland’s most popular artists and represented the country at the Eurovision Song Contest 2008. Within the hard rock group, the Mínus group has had international success. Ólafur Arnalds (born 1986) combines electronic and acoustic music in his compositions that approach classical music. Composer Jóhann Jóhannsson (1969–2018) was also successful with his genre-transcending music; an international career as a film music composer resulted in two Oscar nominations.

Dance

The earliest description of Icelandic dance dates from “Descriptio Islandiæ” (c. 1590), which is, however, fragmentary and partly contradictory. There the chorea and saltatio dances are separated, of which the former danced in pairs on the spot and the latter was a slow ring dance. Probably the Icelandic folk dance has vikivakikinship with French medieval dance branle, a ring dance that can be performed with two steps to the left and one to the right. Just as the bran is believed to have come from Greece to France sometime in the 1000’s, vikivakin may have come to Iceland from Greece and southern Europe, where remains of dances reminiscent of vikivaki have been found. Common to all Iceland dance types, besides great freedom in dance steps, was a vocalist and that you could dance as often as you could. From the 21st century, local dance parties, vigils or slides were organized, which were banned in the late 17th century by the church and the world authorities, who considered them too immoral.

At the beginning of the 19th century, the Icelandic dances were largely extinct, but they were revived in the 20th century. through the dance researcher Sigríður Valgeirsdóttir, who also established Reykjavík folk dance. In 1973, Iceland’s first professional ballet ensemble, the Icelandic dance flock, was formed at the Icelandic National Theater. The first Icelandic ballet created for the group was “Úr borgarlífinu” (1976; “From the City Life”) with choreography, scenography and costume by Unnur Guðjónsdóttir for music by Thorkell Sigurbjörnsson. Katrin Hall (born 1964, 1996) was named Ballet Manager). Since then, the emphasis in its repertoire has been on contemporary dance. Iceland’s most well-known dancer of all time is Helgi Tómasson, who since 1985 is the artistic director of the San Francisco Ballet. Since 2002, the Reykjavík Dance Festival is organized annually with a focus on modern dance and choreography.

folk culture

Ever since the land name, Iceland’s settlement has been along coasts and fjords and on a few islands. The hinterland was long uninhabited. The distances between the farms could be kilometers long. Villages have never existed. At the beginning of the 20th century, when 80% of the population lived in the countryside, there was a vibrant folk culture with roots in the Viking era. Most Icelanders were farmers with sheep farming as the main industry.

In the early Middle Ages, timber houses were sometimes imported from Norway. After the forests were felled, the economy weakened and contacts with the outside world deteriorated during the 1300’s, all houses were built of stone and peat and a minimum of wood. A peat yard consisted of several parallel house bodies. Larger farms had wooden gables. From one of the gables once led into the courtyard with cross connection to the rooms. Often, the farm was built with the cowshed. Sometimes this was under the house to get heat from the animals. Several peat houses were still inhabited during the Second World War. Subsequently, the self-sufficient farmer community quickly dissolved and was replaced by an industrial community. At the beginning of the 1990’s, only 10% of the population lived in rural areas.

In Glaumbær in northern Iceland and in a few more places there are old peat farms, which are now museums. They provide a good insight into the traditional material peasant culture with its richly decorated horn and driftwood articles and its textile art. Folk culture can be studied mainly in the National Museum in Reykjavík and in the open-air museum outside the capital.

Torvgården’s most important room was the “bathhouse” (bath room), which was usually located inside the kitchen. At feasts there were embroideries with scenes from the life of Christ or medieval knight novels. The beds stood along the walls, covered with woven robes and duvets. The bedding was kept in place by “bed boards”. They were usually, like most other wooden objects, ornamented with acanthus loops and a headdress, a Gothic lettering unique to Iceland. Painted objects and furniture were rare. In the bathhouse, the farm people gathered for an evening vigil (summer evening) to listen to high readings from fairy tales, genealogies and poems as well as to oral stories. The Icelandic folk tales were collected in the middle of the 19th century by mainly Jón Árnason.

Of the older domestic annual celebration, mention is made of the extensive celebration of the “first summer day” on a Thursday in the latter part of April, the most important celebration day after the Christmas celebration. They ate and drank well, including special summer day bread, and gave each other summer gifts (known since the 16th century), while the youth gathered for sports competitions and games.

People’s blessings, mainly about the outlaws, the illegals, and the magicians, are also told today in many Icelandic homes. Old folklore is still viable and can affect everyday life and official decisions. Many Icelanders have respect for boulders and other natural formations, where it is believed that the people of hollow (see hollow) lived. Even in the 1980’s, it has happened that newly built roads were forced to give way to such giant stones.

Sports

Iceland’s national sport is the ancient Nordic wrestling glimpse dating back to the Viking era. It is practiced extensively in Iceland and now international championships are also organized.

Handball and football are the most popular ball sports. Iceland’s men’s Olympic handball silver 2008 is seen as the greatest sporting success in the country’s history. Iceland has also taken two Olympic medals in athletics and one in judo. Famous sports profiles include football player Eiður Guðjohnsen (born 1978) and handball player Ólafur Stefánsson (born 1973).

Strength athletes are also popular and Icelandic athletes have been successful both in strength lifting and in more stunted competitions as “the world’s strongest man”.

Riding on Icelandic horses is a popular form of recreation, as is mountain and ice climbing as well as swimming.

Iceland’s national sports organization The Sports and Olympic Association of Iceland was formed in 1912 and merged in 1997 with the country’s Olympic committee (formed in 1921).

Archeology’s testimony of colonization

The oldest traces of settlement in Iceland are mainly settlements and tombs, but some silver treasures have also been found. Visible remnants at town and commercial sites mainly derive from the Middle Ages. Pre-Christian temples, so-called gods of God, are mentioned in medieval literature but have not been able to be archaeologically laid. In addition to the usual methods, so-called te chronology can be used for timings in Iceland, ie. dating using ash finds from various time-bound volcanic eruptions.

There is no evidence that Irish hermits, “papar”, lived in Iceland before the Norse people. Early carbon-14 dates from archaeological investigations have been interpreted as settlements may have existed as early as the 600–700’s, but most archaeologists have not accepted such an early date. Settlements from the 8th century and later seem to largely support the written sources that place the Nordic colonization to the later part of this century (compare Hvítárholt, Reykjavík and Stöng).

The settlement of the Viking Age consisted mainly of individual farms, similar to those in Norway and other Norwegians colonized areas. The dwelling houses were long houses with walls of peat and roof supported by poles in two rows, with wide raised “stools” along the walls and a fireplace in the middle aisle. Fähus was either housed in the longhouse or separately built. Other houses served as workshops, saunas, etc. After the Viking era, the farmhouses were increasingly built together to provide better protection against wind and cold.

The basis for the colonizers’ economy was livestock farming and fishing, but grain cultivation also occurred. Forging and other crafts were often carried out at the farms; human activities went hard for the birch forest found on the island. The tombs were skeletal tombs, usually under flat ground and sometimes richly equipped. Among the gifts and treasure finds are many items from the British Isles. Physical-anthropological studies have shown that the Nordic population was early mixed with elements from it.