Literature

Poetry, mainly love poems (“cantigas de amor” and “cantigas de amigo”) and satirical poems (“cantigas de escárnio e maldizer”), flourished in Portugal in the 13th century. However, much of this poetry was written in other languages: the closely related Galician, Provencal, Italian. The Spanish influence became strong for several centuries; many Portuguese writers wrote alternately in Spanish and Portuguese during the Middle Ages and during Spain’s annexation of Portugal in 1580–1640. In the 16th century, Francisco de Sá de Miranda, after a long stay in Italy, introduced canzone, sonet, ode and other verse forms, which in his poetry gave a national mark. Luís de Camões combined a deep classical education and an encyclopedic knowledge with a perfected language and wrote with “Os Lusíadas” an epic about an entire people. The Portuguese discoveries and conquests gave rise to travelogues and historical works. Portuguese poetry in the 17th century was heavily influenced by the Spanish baroque poet Góngora. In the 18th century, a prose period also for poetry, a number of literary and scientific societies and academies were formed.

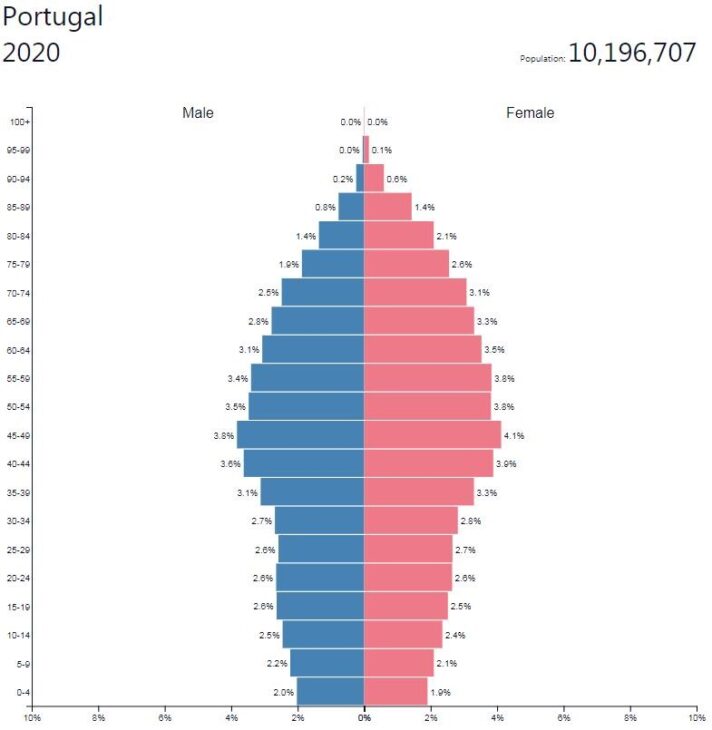

- Countryaah: Population and demographics of Portugal, including population pyramid, density map, projection, data, and distribution.

At the beginning of the 19th century, literature was renewed in Portugal through the romance, whose main representatives were João Baptista de Almeida Garrett (poetry and theater) and Alexandre Herculano (prose). Antero de Quental’s poetry is characterized by an unusually dramatic intensity. João de Deus belonged to a later generation of romantics and, with his natural freshness, came to be regarded as the foremost love lighter after Camões. António Cândido Gonçalves Crespo and António Feijó living in Sweden were influenced by the French Parnass. Camilo Castelo Branco was the great novelist of romance. His hectic life is reflected in a very extensive production. Júlio Dinis represents the transition from romance to realism with his portrayals of life in Porto and Lisbon. Realism’s breakthrough happened with José Maria Eça de Queirós. His novels on Portuguese society made him one of the foremost storytellers in Europe in the 19th century. At the beginning of the 20th century, Raul Brandão and Aquilino Ribeiro developed the realistic novel, and Miguel Torga and José Régio gave it a more psychological touch. The social, neorealistic novel, directed against the Salazar dictatorship, gained a strong position from around 1940 and several decades ahead. Its main representatives include Alves Redol, Fernando Namora, José Maria Ferreira de Castro, Joaquim Paço d’Arcos and later Urbano Tavares Rodrigues and José Cardoso Pires. Following the fall of the dictatorship in 1974, the neorealistic dominance of the prose has given way to an aesthetic diversity that has been expressed most personally by Almeida Faria, António Lobo Antunes and José Saramago (who received the Nobel Prize in literature in 1998). Poetry in Portugal during the 20th century has been very experimental and internationally oriented. In the 1910’s, Fernando Pessoa introduced new ideas from Paris in magazines such as Orpheu and Portugal Futurista. Pessoa’s rich poetic production, whose publication is still ongoing, has aroused great international interest. Also important was the magazine Presença in Porto in the 1920’s. In the 1940’s, a vital surrealist group emerged. In the 1960’s, concrete poetry flourished. Among poets after Pessoa especially Jorge de Sena should be emphasized. Also important was the magazine Presença in Porto in the 1920’s. In the 1940’s, a vital surrealist group emerged. In the 1960’s, concrete poetry flourished. Among poets after Pessoa especially Jorge de Sena should be emphasized.

Drama and theater

Gil Vicente, a playwright in the early 16th century, was the founder of the written theater in Portugal. In the 19th century, João Baptista de Almeida Garrett became a pioneer of a national theater with historical dramas, which received many successors. Towards the end of the century, Eugénio de Castro wrote symbolic plays. Later, the authors of the magazines Orpheu (Teixeira de Pascoais and Fernando Pessoa) and Presença (José Régio and António Botto) helped to renew a theater that has solidified. Raul Brandão wrote works characterized by existential anxiety. Especially the theater that contained social criticism had to fight against the censorship of the Salazar dictatorship.

After World War II, experimental theaters, such as the Teatro-Estúdio Salitre, Pátio das Comédias and the university theaters in Coimbra and Porto, were formed. Alves Redol, Pedro Bom, Jorge de Sena and Bernardo Santareno. Of those who broke through after the 1974 revolution, Carlos Coutinho and Hélder Costa are the most significant.

Film

Portugal’s first feature film was produced in 1918, but a regular film production first began during the takeover of fascism in the 1930’s. For several decades, a domestic mix of comedy and musical predominated, but regime-friendly historical films were also produced. It was not until the 1960’s that the cultural climate became more liberal, and the Novo Cinema generation with names such as Fernando Lopes (1935–2012), António de Cunha Telles (born 1935) and Paulo Rocha (born 1935) became prominent. The situation improved further with the revolution in 1974, after which the Instituto Português de Actividades Cinematográficas was founded with the task of producing, exporting and importing films.

In the 1980’s, a number of new talents were noted, e.g. José Álvaro Morais (1943–2004), Joaquim Pinto (born 1957) and Pedro Costa (born 1959). Even before that, the original João César Monteiro (1939–2003) had made an international claim. Of Portugal’s filmmakers, however, only Manoel de Oliveira – active from 1931 and into the 2010’s – has a world reputation.

Film production in Portugal increased sharply during the 2000’s from 9-10 feature films annually to 23 feature films in 2009, part of co-production with Spain.

Art

Portugal’s art has its roots in Roman culture. However, of the Romanians’ long-standing occupation, the traces are quite few, especially in northern Portugal. Portuguese art was later influenced by Moorish culture, but today the traces of Moorish art are also rare. A Portuguese painting school grew under the Flemish influence towards the end of the 14th century. Flemish painters established themselves in Portugal and Portuguese painters resided in Flanders. During the latter part of the 1400’s, Nuno Gonçalves, a foreground figure in Portuguese painting, achieved great reputation with, among other things, impressive altarpieces. Domestic painting schools were later established in i.a. Lisbon and Viseu. Nuno Gonçalve’s foremost successor during the 16th century is the Vasco Fernandes operating in Viseu, also known as Grão-Vasco.

After Manuel I’s death and with the decline of the spice trade, Portuguese resources became scarce, and in addition, the Spanish dominion between 1580 and 1640 had a long-lasting inhibitory effect on the creation of art. With the Renaissance, Italian influence became prominent in religious painting as well. During the Baroque period, the sculpture art influenced by Italian and French masters flourished. Very original were gilded and richly carved altarpieces in wood (talhas) and illusory painted ceiling paintings even under rococo. Rome continued to attract the Portuguese artists during this time. Two famous painters, Vieira Portuense and Domingo António de Sequeira, should be mentioned, and in the art of sculpture Joaquim Machado de Castro is the most prominent name. During neoclassicism and romance, the visual arts were dominated by French-inspired naturalism. It is mainly when Portuguese art loses its original features.

With the exception of the Cubist painter Amadeo de Souza-Cardoso, Portuguese artists participated only marginally in the modernist movements during the first half of the 20th century. The young Portuguese artists often lived in Paris and were influenced, among other things. by Cézanne and by the Cubist experiments; José de Almada Negreiros is the dominant name for several decades in the modernist visual arts. One should, however, mention Maria Elena Vieira da Silva, who was active in Paris and who is regarded as the forefront of the so-called Paris school.

Portugal’s art life after 1950 has been largely influenced by the cultural isolation that the Salazar regime kept the country in until 1974. This has meant that a large part of the country’s artists have applied abroad and have built up their artistry there.

One of the artists who left the country and who is also the one that has received the greatest international attention is the figurative painter Paula Rego, active in the UK since 1952. Others in the painting tradition from about the same period that have been significant are José de Guimarães, Álvaro Lapa and Angelo de Sousa and Lourdes Castro and René Bertholo who are based on painting but also worked with different assembly techniques. More purely conceptual artists from the 1960’s and 1970’s that influenced the country’s art life are Helena Almeida and Fernando Calhau.

Another of the country’s most internationally prominent artists is Julião Sarmento, who works with both painting and installations. Sarmento made his breakthrough during the emotionally charged neo-expressionist wave of the 1980’s. The same generation also includes installation artist Pedro Cabrita Reis; photo artists Jorge Molder, Paulo Nozolino and Daniel Blaufuks, as well as multimaterial artist and former dancer João Penalva. To some extent, Penalva also forms a bridge between the emotional art of the 1980’s and the more situational installations of the 1990’s.

Other artists who had their breakthrough in the 1990’s are Rui Chafes, Angela Ferreira, Miguel Palma, Rui Toscano and the French-born Joana Vasconcelos. In the early 2000’s, a number of artists have also emerged who have the film as the main or recurring medium, such as Vasco Araújo, Alexandre Estrela, Filipa César, João Onofre, Pedro Paiva, João Maria Gusmão and João Tabarra. In this context, mention can also be made of Maria Lusitano (Santos), who was occasionally active in Sweden. Another important person in the video art is Pedro Costa, who is, however, better known for his feature films.

Architecture

The Roman presence in Portugal has left behind important building memories such as the floor mosaics in Conímbriga as well as the aqueduct and the temple in Évora. Only a few architectural elements have been preserved from the Moorish period. in rebuilt mosques. Since the Moors were finally expelled from Portugal, the Romanesque building style was spread with influences from, among other things. Burgundy and Languedoc across the country, best represented in the cathedrals of Coimbra, Lisbon, Braga and Porto. The Cistercian Monastery of Alcobaça, founded in 1147, is the country’s earliest example of Gothic. Gothic in Portugal reached a climax in the convent of Santa Maria da Vitória in Batalha, founded about 1387 in memory of the 1385 victory over the Castilians.

The new wealth that arose since the Portuguese seafarers opened the sea route to the Far East allowed the construction of magnificent works. Also, contacts with distant cultures in Asia, Africa and South America came to characterize Portugal’s architecture during the 1400’s and 1500’s. An abundantly rich decoration style, Emanuel style, characterized by imaginative ornaments in the form of, among other things. algae, coral, rope and cobwebs, emerged during Manuel I’s reign of 1495–1521. The most prominent examples of this style include the monastery Mosteiro dos Jerónimos (c. 1502–72) and the fortress tower Torre de Belém (1515–21) in Lisbon and the Church of the Knights of Christ in Tomar.

The Emanuel style was gradually replaced by a more restrained style, with influences from the Italian Renaissance. Architectural architecture in Portugal was dominated by Baroque architects from Italy and Germany; One example is the monastery facility in Mafra (1717-30), erected by the German Johann Friedrich Ludwig. During both the Renaissance and Baroque, colorful and patterned tiles, azulejos, were often used to cover the walls of churches and castles.

During the 19th century, as a background to the new bourgeois society, classical and historical styles were developed in the architecture of Portugal, first a new manual style and a somewhat later Romanesque style. In Porto, England was linked to England as a model for New Palladianism, with the stock exchange (1842) by Thomaz Augusto Soller as an example. The architecture of modern Portugal was formed in a southern region around Lisbon and a northern, more progressive, region with Porto as the center. Porto School developed a rationalist architecture. An architectural congress in 1948 marked with political undertones a focus on international modernism. During the 1950’s, inspiration was drawn from Italian neorealism and contemporary Scandinavian architecture; The Church of Penamacor (1951) by Nuno Teotónio Pereira is an example.

Music

Classical music

In the medieval church, the Mozarabic song, similar to the Spanish one, was used until it was replaced by the Gregorian. The profane song is represented, among other things. of the Spanish-Portuguese-Galician cantigas. During the Renaissance, Portugal was influenced by the Dutch polyphony, initially represented by, inter alia, Damião de Gois (1502–74) and António Carreira (born ca 1520, died ca 1597).

Polyphony flourished from the beginning of the 17th century, with organist Manuel Rodrigues Cielho (born about 1555, died in 1633). Cantatas and operas were composed under Italian influence during the 18th century by a.k.a. Francisco António de Almeida (1702–52) and André da Costa. Italian Domenico Scarlatti was active at the Portuguese court in 1720–29 and had a great influence on Portugal’s music life. Carlos de Seixa’s (1704–42) composed harpsichord in rococo style.

During classicalism operas were played by João de Sousa Carvalho (1745–98) throughout Europe. Luís de Freitas Branco (1890–1955) was an eclectic innovator with some influence from Impressionism. Twilight technology and serialism were used by Álvaro Cassuto (born 1938) and Jorge Peixinho (1940–95); Felipe Pires has worked among other things. with electro-acoustic music.

Folk and popular music

Work songs occur in Portugal in connection with, among other things. plowing, fishing and house building. At festivities such as Pentecost, Thirteen Day and Harvest Festivals, lyrical songs can be performed, usually in four-line copla form, with texts that deal with different aspects of life. Other singing styles are lullabies, despedidas (farewells) and saudas (longings), as well as ballads with roots in the medieval knight’s post.

Common folk instruments are the guitar-like violas (usually five-stringed), violão (six-stringed), viola de arame and cavaquinho (small four-stringed, the origin of the ukulele) as well as accordions, violins, drums such as tambores and adufes, sackpipe gaita and fiddle rebec.

The song style fado is believed to have emerged in Lisbon during the 19th century; it is accompanied by viola and so-called Portuguese guitar. Singer Amália Rodrigues was the one who made fado internationally famous in the mid-1950’s, and she is still Portugal’s best-known artist. A new generation of fado musicians, such as the singers Mísia (really Susana Maria Alfonso de Aguiar, born 1955), Camané (really Carlos Manuel Moutinho Paiva dos Santos, born 1967), Cristina Branco (born 1972), Mariza (really Marisa dos Reis Nunes, born 1973) and Mafalda Arnauth (born 1974)), has revitalized the fadon and introduced it to a new audience. The group Madredeus with singer Teresa Salgueiro (born 1969) combines fado with other traditional and modern folk music and received an international breakthrough through her participation in Wim Wender’s film “Lisbon Story” in 1994.

However, popular music in Portugal is not just fado. The indigenous rock music broke through in the 1980’s with, among other things, Jorge Palma (born 1950) and Rui Veloso (born 1957) as well as groups such as Xutos & Pontapés and Mão Morta. Later heavy metal was introduced, with groups such as Moonspell and electronica, where e.g. the group Buraka Like Sistema mixes techno with African rhythms.

The immigration from the former colonies in Africa has brought with it music traditions mixed with the Portuguese, such as in the music of Lura (actually Maria de Lurdes Assunção Pina, born 1975) and Sara Tavares (born 1978), both originating in Cape Verde. The music styles kizomba and kuduro from Angola have also become popular in Portugal.

Dance

In northern Portugal, folk dances are powerful with high hopes, in the south the movements become softer. Of high age are cane dances and morisca. Fandango is available in many types. In the Algarve there is the polka-like corridinho, while the dance chamarrita is typical of the Azores. A popular and popular folk dance today is the lively virus. Portugal has two major dance ensembles: the Gulbenkian Ballet (founded in 1965), focused on contemporary dance art by contemporary choreographers, and the National Ballet (founded in 1977), which is linked to the São Carlos opera.

folk culture

The Portuguese traditional culture is obviously a provincial part of the Iberian peninsula and, like the Spanish, has its roots in ancient Iberian and Roman; influences from the Germanic migration and the Moorish medieval (windowless houses, women in veil) are also evident. However, Portugal has turned its face to the Atlantic, while mountains and sparsely populated have made the eastern border with Spain an equally distinct back, over which the cultural impulses have been rather insignificant. Shipping contributed both to better economy and to more intensive relations with Western Europe and Africa, which later also left traces in the population, as the Portuguese were unusually positive to racially mixed marriages.

The settlement, which in the south was characterized by the dominance of large goods and in the north by self-sufficient small farms, consisted in the northeast of elongated, narrow villages along the valley sides and in the north-west and central Portugal of both single farms and small and large villages. In the south, the dense cluster villages of the uncultivated agricultural workers were often laid on the hills around the parcels’ farms, a system considered to go back to Roman tradition. The houses are often built of limestone, in the mountain areas on two floors with the animals in the lower. In the south, the dwelling houses are lower and the farm buildings are gathered into a closed square. The old-fashioned elements include pillars (sometimes in dampers or braids), the fishermen’s pile buildings and the shepherd vaults. On the coast, a prominent boatbuilding has been developed.

In the case of folklore, one can note the internationally famous fados (see fado), the local markets, often at the same time religious (saint) celebrations, celebrations, and the more regional, large folk festivals, romarias. Faith in evil eyes with the resulting use of amulets has come into our own time. Folk-poetry has never attracted any greater interest from a literary or literary perspective, and the country’s folk tales are among the poorest documented and least known in Europe. Folklore studies and documentation are conducted by the Instituto português de artes e tradições populares in Santiago do Cacém; in Lisbon there is a Museu de arte popular and in Porto a Museu de ethnologia. See also the Music section (above).