Literature

Slovak literature written in Latin or Czech with Slovak elements received a boost from the 17th century, with eg. the Protestant hymn book by Jiří Třanovský (1636), the Catholic “Cantus Catholici” (1655), the note-learning “Valaská škola” (‘The Heraldry School’, 1–2, written 1755, printed 1830) by Hugolín Gavlovič in verse. In parallel, a lyrical and epic folk poem emerged with the noble robber Jánošík as a popular theme.

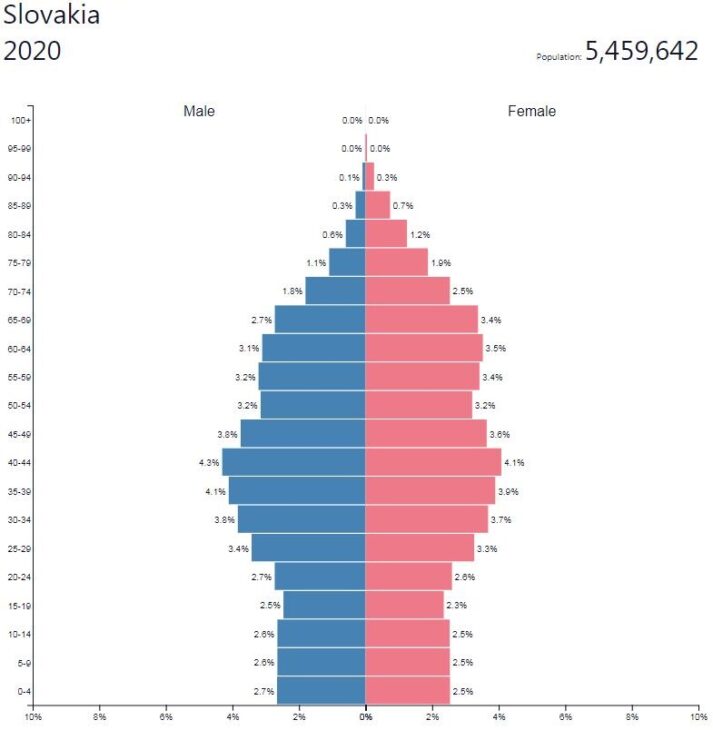

- Countryaah: Population and demographics of Slovakia, including population pyramid, density map, projection, data, and distribution.

During the Enlightenment, literature became an important factor in the awakening of the Slovak nation; Patriotism and Slavic community were the main ideas. Anton Bernolák tried in 1787 to create a Slovak written language, which was used by Ján Hollý in his classic poetry. Other Slovak writers such as Ján Kollár and PJ Šafárik wrote in Czech. From 1843, when the unified Slovak writing language was created by Lūudovít Štúr, Slovak was preferably used. Around Štúr, the Slovak romantics gathered, poets such as Ján Botto, Samo Chalupka, Janko Králū, Janko Matúška, and Andrej Sládkovič and prose writers such as Ján Kalinčiak and JM Hurban. A generation of realists then emerged with writers such as SH Vajanský and Martin Kukučín and most notably the poet PO Hviezdoslav. They portrayed the hometown, the oppression of the Slovak people and the resistance to the Hungarians. They inspired younger realistic writers such as Terézia Vansová, Elena Maróthy-Šoltésová, Lūudmila Podjavorinská, Timrava, Jozef Gregor Tajovský, Ladislav Nádaši-Jégé and Janko Jesenský.

At the beginning of the 20th century, the symbolist Ivan Krasko laid the foundation for modern Slovak poetry, and after the advent of Czechoslovakia in 1918, Slovak literature developed dynamically and multifaceted. In poetry were noted the vitalist Ján Smrek and the neo-symbolist EB Lukáč. Around the magazine DAV, the left avant-garde was gathered with poet Laco Novomeský and Ján Rob Poničan. Socialist prose was written by Fraňo Králū and Peter Jilemnický. Psychological novels by Ján Hrušovský, Gejza Vámoš and Jozef Cíger Hronský have expressionist features, while Milo Urban wrote novels with social compassion. During the 1930’s, the so-called Catholic modernism was developed by Rudolf Dilong and PG Hlbina. Slovak surrealism was represented by Rudolf Fabry, Štefan Žáry and Vladimír Reisel.

During the communist years of 1948–89, the literature was characterized by political adaptation. After 1956, several writers tried to liberate themselves from the restrictions in the 1960’s. Among Stalinism’s foremost critics are Dominik Tatarka and Ladislav Mňačko. The poets include Miroslav Válek and Milan Rúfus, and by the prose writers Vladimír Mináč, Alfonz Bednár and by later writers Vincent Šikula, Rudolf Sloboda, Ladislav Ballek, Dušan Mitana and Peter Jaroš. Karel Pecka had a publishing ban until 1989, but today is considered one of the foremost depictions of Eastern European everyday life, especially in the novel “Gallerian” (written 1976). A popular genre in the early 2000’s is fantasy with writers such as Juraj Červenák and Dušan Fabian.

Of the children’s book authors, Klára Jarunková, Lūubomír Feldek and Krista Bendová are the most central.

Drama and theater

Slovak theater was developed by amateurs during the 19th century and is associated with Ján Chalupka’s comedies. It was not until 1920 that a professional stage, the Slovak National Theater, was opened in Bratislava, and in 1924 the East Slovak theater was added to Košice. The profile of the National Theater was mainly formed by Ján Borodáč. There, among other things, realist Jozef Gregor Tajovský’s folk plays and Ivan Stodola’s comedies and later Július Barč-Ivans and Štefan Králik’s psychological dramas. Anti-fascism characterized many playwrights such as Peter Zvon and directors such as Andrej Bagar and avant-garde artist Ján Jamnický.

After 1945, new theaters were opened and in the 1960’s several small scenes were also opened. Among the playwrights are Leopold Lahola, Peter Karvaš, Ivan Bukovčan and later Ján Solovič and Igor Rusnák. From the 1980’s, satire became important with names such as Lūubomír Feldek, Milan Lasica, Július Satinský, Ján Filip, Milan Markovič and Stanislav Štepka from the naivist Radošinateatré. Luba Lesná and Milan Richter include contemporary dramatists. In 2007, a new theater building was opened in Bratislava for the Slovak National Theater.

Film

The first Slovak film, “Jánošík”, was made in 1921 by Jaroslav Siakel (1896–1997) with US funding, but Slovak film production remained sporadic during the 1920’s and 1930’s. Only with the nationalization of the film industry after the Second World War and the establishment of the Hummingbird Studios in Bratislava, conditions were created for continuous Slovak film production, although most Slovak film workers moved to the better resources in Prague. Among others, Elmar Klos (1910–93) and Ján Kadár (1918–79), who made the Oscar-winning “The shop on the main street” (1965), began their courses in Slovakia.

Štefan Uhers (1930–93) “Sinko v sieti” (1963) broke out of the social realism and laid the foundation for a new, experimental film wave of young film workers. Dušan Hanák (born 1938) and Juraj Jakubisko (born 1938; “The Gycklarna”, 1971) were among those who followed in his tracks. During the 1970’s, the film was kept in political lapses, but the decade after that, Uher, Hanák and Martin Hollý (1931–2004; “Signum Laudis”, 1980) re-asserted thematically bold, formally suggestive works. After the division of Czechoslovakia, Hanák in particular has played a role in the democratic construction of the country.

Among new names is Martin Šulík (born 1962) with films such as “Cigán” (2011; English title “Gypsy”).

Slovakia produces about four feature films a year.

Architecture

With the cities and mining, German building culture came to medieval Slovakia. The strangest Gothic building is the Cathedral of St. Elisabeth in Košice, begun about 1390. Also noteworthy is the Church of Jacob in Levoča, also from the 1300’s, with rich decor. A very early example of Renaissance architecture is the Bardejov City Hall from the beginning of the 16th century. The University church in Trnava, in the Baroque style, was erected in the 1630’s by Italian builders.

In the Carpathians, there has been in the present a rich wooden architecture. Suggestive examples are a number of wooden churches from the 18th century, e.g. in Ladomírová and Lukov-Venécia. Characteristic of the 18th century is otherwise the baroqueization of churches and cities. The classicist ideals of the late 18th and early 19th centuries were widely applied, also in the countryside, to the estate of Hungarian landowners.

Until 1918, Slovakia’s architectural history was closely associated with Hungary. In the early 1900’s, Dušan Jurkovič sought to reconcile modern ideals with indigenous tradition. A pioneer of modernism was Emil Belluš. The post-war building program was reconstruction and industrialization. After independence, the construction of i.a. office buildings in international postmodern style, but efforts are also being made to preserve and renovate 20th century modernism buildings.

Music

The Slovak folk music is in its entirety closely related to the music of neighboring countries and other Slavic peoples and stylistically influenced by Western European music. A significant part is based on vocal forms. Most of the song is unanimous, but multi-part song occurs. Most of the folk music is dance music, also the usual songs, with melodies and accents that closely follow the text.

Several stylistic strata are expected: age-old magical and ritual music with short recitative stanzas and small intervals; farmers’ music built around the quarters as the dominant interval; the shepherds’ free rhythmic melodies; the “new style” with harmonious four-line bias, often in syncopated rhythm and with repetition of the first phrase a quarter higher; as well as the 20th century style with widespread multi-partisanship, larger ensembles, emotive execution and conscious revival of older styles. Popular instruments are the bagpipe (gajdy), two-line accordion (heligonka), shepherd’s flutes (fujara, dvojačka) and violin. Small ensembles are common, with violin, viola and bass or with strings, clarinet, chopping board (cimbál) and base. During the 20th century, the Blue Chapel also gained great popularity along with large folklore ensembles, with instrumental music, song and dance. An old repertoire of ring dances was replaced from the 18th century onwards by a large number of pair dances in even or varying tempo.

Liturgical manuscripts, the oldest from the 8th century, testify to a rich church music. In the cities, art music was cultivated in close proximity to Central European music life; as early as 1350 there are tracks by professional musicians in cities such as Bardejov and Banská Stiavnic. Several major composers were active in Slovakia. Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven and Liszt. Significant native composers during the Viennese classical era was the violinist and organist Anton Zimmermann (born about 1741, died 1781) and pianist and pedagogue Franz Paul Rigler (born about 1747, died 1796), and the Bohemia-born and in Slovakia acting Jiří Družecký (1745-1819).

During the flourishing of the romantic style of the 1820’s, music was divided; while the nobility raved about Hungarian styles, the urban population preferred other German music. From the middle of the 19th century, a national romantic style became dominant. Ján Levoslav Bella (1843–1936), Mikuláš Schneider-Trnavský (1881–1958) and Viliam Figuš-Bystrý (1875–1937). During the 20th century, classical and romantic styles continued to dominate, among other things. through composers such as Alexander Moyzes (1906–84), Ján Cikker and Eugen Suchoň.

A professional public life of music grew after 1918. In Bratislava, a school for higher music education was opened in 1919, an opera was founded in 1920 and a philharmonic orchestra in 1949. Folk music, which was institutionalized as early as the end of the 19th century, was placed in the nation’s center by cultural politics after 1948. Composers were encouraged to use folk music in their works, a state folklore ensemble was formed in 1949 and a large number of amateur folk music ensembles emerged.

Jazz and other American forms of music were counteracted as bourgeois decadent but still gained some popularity, especially in the cities.

In the 1960’s a vibrant popular music emerged with folk music forms, songs, rock, jazz, bossa nova and various genre mixes. After the velvet revolution in 1989, folk music continued to be encouraged as a national expression, and a number of new styles have become popular, such as American rock, grunge and hip hop, British pop and musicals.

Estimated Slovak artists include organist and symphony rocker Marián Varga (born 1947) with the band Prúdy (founded 1962), rock musicians Dežo Ursiny (1947–95), Peter Nagy (born 1959) and Richard Müller (born 1961), groups such as Tublatanka, Modus and Elán and alternative rock groups such as Bez ladu a skadou, DESmod and IMT Smile. Mention can also be made of pop singer Jana Kirschnerová (born 1978), Peha group with singer Katarína Knechtová (born 1981), thrash metal group Majster Kat and hip hop group Kontrafakt. However, Slovak popular music has been difficult to reach outside the country.

Dance

Most folk dances in Slovakia are pair dances. The older ones consist of jump dances (odzemok) and spin dances (krútivé tance). From the second half of the 19th century, polka, waltz and csardas were spread. During the latter part of the 20th century, dance life was dominated by modern European and American social dances. Ballet ensembles were founded at the National Theater in Bratislava in 1920 and in Košice in 1947. During the post-war period, several dance scenes were created in various locations in Slovakia, as well as three professional folklore ensembles and a large number of amateur groups. Among the leading ensembles in the early 2000’s, apart from the National Theater, Balet Bratislava.

folk culture

The culture of the people of Slovakia occupies a special position among the West Slavs, including by the fact that the Slavs lived for a thousand years within the Hungarian state formation and that during this time a Slovak ethnicity crystallized which in several respects distinguished them from their Slavic neighbors. This, as well as the fact that the Slovaks were a poor and child-rich mountain people isolated in the Carpathian valleys, has contributed to the preservation of a relatively diverse folk culture. Based on popular culture, dialects and minorities (Germans, Hungarians, Carpathians, Jews and others), the country can be divided into a western and an eastern part, the lowland to the south and the mountain area. These cultural areas are oriented towards different sources of impulse. Since the Middle Ages, there was a migration of Carpathian shepherd culture from the east, which prevailed in the high-level dairy farming, in the tissues and in the national costume. Western influence is evident in the buildings (row houses, surrounding farms), in the church customs and in the crafts (eg glass painting, blueprints, embroidery and embroidery). The lowland folk culture shows close kinship with Hungary (home decor, costumes, dances and above all folk music).

As far back as the 20th century, Slovakia was a prominent agricultural land with dominant livestock management, forestry and significant rural crafts. The country’s limited resources have contributed to large emigration and widespread labor migration to neighboring countries. The Slovaks were well-known for their ambulatory craftsmen (wire and tin workers, glassmasters, basket makers, etc.) and farm traders (with sales of, for example, spices, household goods, medicinal plants and textiles), which have not only crossed large parts of Europe since the 1600’s. but also western Asia. The countryside had well-developed local organizations, which, in addition to regulated industries, were also responsible for shaping social life. In folklore, stories with historical motives about Turks, robbers and historical figures can be mentioned,

Sports

The most prominent sports in the country are ice hockey and football. Slovakia took the World Cup gold in ice hockey in 2002 and has had a number of successful players in the NHL. Among the most prominent are Peter Št’astný (born 1956), Miroslav Šatan (born 1974), Zdeno Chára (born 1977) and Marián Hossa (born 1979). Slovak players also contributed to great success for Czechoslovakia, including six World Cup golds 1947–85.

In football, Czechoslovakia took the World Cup silver in 1962 and the European gold in 1976, both times with a significant element of Slovak players.

Other Slovak sports stars include figure skater Ondrej Nepela (1951–89) and pedestrian Jozef Pribilinec (born 1960). After independence, the country has also had remarkable success in canoe slalom. In the Tatra Mountains there are excellent conditions for practicing winter sports.