Literature

See also Ireland (Literature) and Scotland (Literature).

The Ancient English Period (to about 1100)

The emergence of a literature was favored by the narrative heritage brought by the Germanic peoples to England in the 14th century, but also by the early founding monasteries and by the bards, “scops”, who recited poems at various kings and temples. About 30,000 lines of poetry are preserved, but the only known author names are Caedmon and Cynewulf. The oldest preserved poem is from the 600’s.

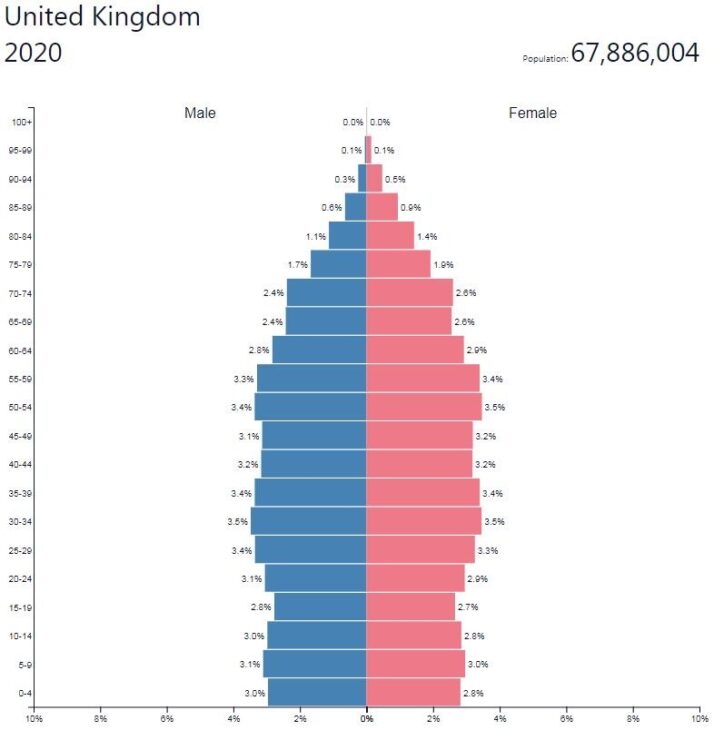

- Countryaah: Population and demographics of United Kingdom, including population pyramid, density map, projection, data, and distribution.

The heroic epic “Beowulf” is the greatest poem of the period. There and in several other poems, pagan and Christian are united. A notable group are the elegant monologues where an anonymous bald tells about his dangerous life. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle includes the powerful patriotic poem about the Battle of Maldon 991 between Anglo-Saxons and Vikings. Of particular artistic value in religious poetry are the visionary poem “The Dream of the Rood” and Cynewulf’s contemplative poems.

Prose in native language was not least cultivated at the court of Alfred the Great, where several learned works in Latin were translated. Archbishop Wulfstan belongs to York at the beginning of the 11th century, who in a famous sermon painted the horrors of the Danish ravages. Despite this, the period was rich in poetry.

The Middle English period (to about 1500)

The Norman conquest of 1066 meant that the English was forced by the French as an official language for three centuries. Literally it meant continental impulses, which led to an outstanding flowering in the latter half of the 1300’s.

As early as 1200, a chronicle in Latin written via French was translated into English verse by Layamon, and native material in the form of fairy tales and history. The Art History, was utilized. The Christian verse poetry consists of Bible paraphrases, handbooks for the devil, saint legends, etc. At most, the spiritual poetry reached the anonymous visionary poem “Pearl” (late 1300’s) and in short lyrical poems; it, like nature and love poems, is still alive. The Old English meter was increasingly replaced by rhymed verses, so as early as the 13th century romances, verse stories with French role models but genuine native character. Metric and narrative refinement show e.g. “Sir Gawainand the Green Knight ”from the latter half of the 1300’s. Then the highlight is reached with the humorous and realistic narrative genius that characterizes Geoffrey Chaucer’s “Troilus and Criseyde” and “The Canterbury Tales” (1387 onwards; “Canterbury stories” or “Canterbury tales”). This politically troubled time is reflected in the long visionary poem “Piers Plowman” (‘Peter the Plower’) with its vivid contemporary depiction and satire, including of the priesthood.

War with France and Civil War contributed to making the 15th century a literary arid period, but two important events belong to the end of the century: William Caxton introduced the printmaking art, and Thomas Malory compiled on living prose the Artur saga stories in “Le Morte d’Arthur” (‘ Artur’s death ‘).

The early Tudor era; the Elizabethan and the Post-Elizabethan period

Continental relations became more vibrant during the reign of Henry VIII (1509–47). New verse forms such as sonnet and blank verse were introduced by Thomas Wyatt and Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey.

This was the time of the English humanists with John Colet and Thomas More as central figures. Native scripts and mirrors were written by Roger Ascham and Thomas Elyot, there came new Bible translations and in the traces of the religious persecution religious writings. The increasingly significant interest in the mother tongue is reflected in Thomas Wilson’s “Art of Rhetorique” (1553) and of English history in several chronicles, of which Raphael Holinsheds became the most important through its importance to Shakespeare.

The period circa 1590 – circa 1610 was England’s first truly great cultural heyday, especially in drama. The interest of the time for antiquity was manifested through a number of translations, which probably also John Florio’s translation of Montaigne had pervasive significance for Shakespeare.

The greatest poetic work was Edmund Spencer’s extensive allegorical, patriotic epic “The Faerie Queene” (1590-96). Spenser, Shakespeare and others wrote sonnet suites, a fashion of the time, playwright Ben Jonson love poems, idols and satires. John Donne began with outspoken erotic and satirical poems in the 1590’s but gained its lasting significance through his later intense love poems and religious poems, with their subtle imagery (see Metaphysical Poetry).

Also captivating were Donna’s prose views and sermons. They were preceded by such different prose works as John Lylys in precise style written “Euphues: the Anatomy of Wit” (1578) and “Euphues and his England” (1580), Philip Sidney’s shepherd’s post “Arcadia” (published in various versions 1590 and 1593), as well as satirical transcripts and stories from everyday life and from foreign environments, a first development towards the novel, i.a. by Thomas Nashe. The period also includes Francis Bacon’s essays and philosophical works.

17th century (from about 1625)

There are marked boundaries between Karl I’s conflict-filled time, the Puritan-dominated period 1649-60 and the restoration period 1660-85 with its strong reaction to Puritanism. In poetry, the tradition from Donne was initially continued by Christian poets such as George Herbert and Henry Vaughan as well as by Andrew Marvell, who used Donne’s “metaphysical” grasp of love poetry and political poetry. Another direction, “cavalier poetry”, was spiritual life-giving.

The greatest skull of the century, John Milton, in Puritan service, but a freedom and beauty-loving man with in-depth education, wrote lyric and the mask play “Comus” (1637) in younger years, but devoted the years before and after Karl I’s execution to polemical authorship, inter alia in the grand defense of freedom of the press, “Areopagitica” (1644). His great works, the Christian epic “Paradise Lost” (1667; “The Lost Paradise”) and the biblical drama in classic form “Samson Agonistes” (1671; “Samson”), were added during the restoration period, when Milton was frozen by the ruling establishment.

A great religious prose appeared at this time: John Bunyan with “The Pilgrim’s Progress” (1-2, 1678-84; “Christian’s Journey”). A tolerant view of man and god can be found in the physician and style artist Thomas Brown’s “Religio Medici” (“A Doctor’s Religion”, 1642).

The restoration period was characterized by three particular tendencies: neoclassical taste in poetry; a more modern, simpler prose style, prominent among others. in John Dryden’s literary criticism and promoted by the newly formed Royal Society’s clarity ideal, as well as new life in the theater. In poetry, Dryden contributed with, among other things, long political satires written on five-footed, paired rhymed Jambian verse, “heroic couplets”, which became the foremost meter of neoclassical style. Extravagance characterizes Samuel Pepy’s famous and only fully published “Diary” (“Pepy’s Diary”) from the years 1660-69. His and John Evelyn’s extensive diaries provide invaluable insights into the life of the period.

For the first time, female writers began to listen. In addition to comedy, Aphra Behn wrote a philosophical novel in an exotic setting, “Oroonoko” (c. 1688).

1700’s

The beginning of the century is called the Augustan Age, as representative writers saw themselves as heirs to the great Roman Shalomites of Augustus. But they lived in a time of party bickering and prestige war – relentlessly revealed by Jonathan Swift in “Gulliver’s Travels” (1726; “Gulliver’s Travels”) – but also of increased religious tolerance and enlightenment.

The introductory stage was marked by two phenomena: first the continuation of the neoclassical taste in poetry with Alexander Pope as the main name and as Swift in the prose sovereign satirical, and the new life for the prose through Joseph Addison’s and Richard Steeles popularly written magazines for the middle class. In addition, there was a form of prose story that, in a time of increased literacy, could reach a wider audience: the novel in a more modern sense was initiated by Swift and Daniel Defoe.

The view of time as the age of strict taste and reason is a simplified picture: Swift and others wrote unconventional verses. enthusiasm for simple country life or as melancholic self-reflection, was passed on by the next generation of poets, including Edward Young, James Thomson and Thomas Gray. The image of openness to other tastes also included the extensive criticism and publishing activities of Shakespeare.

The novel was developed in many ways. At the turn of the century, Samuel Richardson appeared with meticulous psychological analysis in the epistles “Pamela” (1–2, 1740–41) and “Clarissa” (1–7, 1747–48). Henry Fielding’s “Joseph Andrews” (1742; “Joseph Andrews and His Friends”) and “The History of Tom Jones, a Foundling” (1749; “Tom Jones or the Founding Child”) are characterized by broadly girlish narrative but above all of humanity and tolerance. In “The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman” (1–9, 1759–67; “Well-Born Mr. Tristram Shandy: His Life and Sentences”), Laurence Sterne exhibited a stunningly modern storytelling technique in consciously changing moods. For the continental contemporary, Sterne became more famous for “A Sentimental Journey” (1768; “A Sentimental Journey Through France and Italy”). International reputation also received Oliver Goldsmith’s friendly, psychologically revealing “The Vicar of Wakefield” (1766; “The Land Priest of Wakefield”). Samuel Johnson wrote the illusion-free story “Rasselas, Prince of Abyssinia” (1759), but his greatest contribution was an English lexicon and a Shakespeare edition. About Johnson deals with probably the most well-known biography of English literature, written by James Boswell, author of self-revealing diaries. Strong literary style consciousness showed historian Edward Gibbon and conservative Whig politician Edmund Burke. About Johnson deals with probably the most well-known biography of English literature, written by James Boswell, author of self-revealing diaries. Strong literary style consciousness showed historian Edward Gibbon and conservative Whig politician Edmund Burke. About Johnson deals with probably the most well-known biography of English literature, written by James Boswell, author of self-revealing diaries. Strong literary style consciousness showed historian Edward Gibbon and conservative Whig politician Edmund Burke.

Towards the end of the century, two different kinds of novels dominated: the horror novel (gothic novel), represented by a.k.a. Horace Walpole and Ann Radcliffe, and a socially critical, radical novel represented by William Godwin. The number of female writers increased significantly. Fanny Burney’s observation of society’s upper strata pointed to Jane Austen.

The romance was forbidden, among other things. through the interest in primitive or popular poetry, which was expressed in aesthetic theory formation and in the publishing of ballad collections. The enthusiasm for James Macpherson’s Ossian poetry became strongest on the continent; see ossian poetry.

Two very different lines predated the romance: the Scotsman Robert Burns, who on dialect wrote love lyric and drastically narrative hometown poems, and the deeply original William Blake, a religious visionary, who in itself united both the poet and the visual artist.

1800’s

British romance developed in the context of the French Revolution, the Napoleonic Wars and the subsequent unrest in society. Most poets were socially and politically aware. No strictly romantic school was formed. William Wordsworth’s and ST Coleridge’s collaboration in 1798 had resulted in their “Lyrical Ballads” with a program statement by Wordsworth in the second edition. Such is also found in some chapters of Coleridge’s “Biographia Literaria” (1817). Broadly common to the Romantics is their belief in the imagination’s ability to reach a true truth beyond reason, as well as their assertion of individual design and of poetry as an expression of one’s own self. Byron is difficult to capture in a romantic pattern, and what stands out most from his lavish production is instead “Don Juan” (1819-24), a sumptuous narrative and contemporary revelatory poem. The commute between high-spirited future faith and deep personal pessimism was characteristic of PB Shelley. For John Keats, a defining motif was the contrast between the enduring beauty of art and nature and the brevity of human life.

Walter Scott’s popularity as an epic bald was clouded by Byron’s. Instead, Scott’s storytelling genius got an outlet in historical novels with colorful background and bipartisan drawing, free from problem debates and psychologizing. Of a completely different kind, Jane Austen, one of the great female writers, was amused in her chilly revelation of vanity and other weaknesses.

In the same period, two phenomena were included in the prose, partly the contemporary magazines, e.g. “Edinburgh Review”, founded in 1802, partly a spiritual essay represented by Thomas de Quincey, William Hazlitt, Leigh Hunt, Charles Lamb and WS Landor. Hazlitt and Coleridge also deepened the Shakespeare criticism.

During the Victorian period, the novel developed in several directions, including in the form of social criticism in a time of deep social divisions. For the afterlife, Charles Dickens, George Eliot, WM Thackeray, Charlotte and Emily Brontë appear to be the most significant around the middle of the century. Dickens is second to none as a linguistic virtuoso and through his mind for the comic and misery of existence. Eliot wrote intelligently about the griefs and tragedies of unaffected people. Popular in the contemporary were among many others William Collins, one of the detective novel’s pioneers, and Anthony Trollope, who, with sharp but friendly observation, revealed church and political power play.

In poetry at and after the middle of the century, Matthew Arnold and AH Clough expressed their uneasiness to a time-honored spirit. The linguistically masterful but thematically superficial Alfred Tennyson reflected in “In Memoriam” (1850) the crisis of faith that, for many, had its roots in Bible criticism and the new natural science. Instead, Robert Browning excelled in subtly revealing people’s innermost motives, preferably embedded in the Italian Renaissance environment. Browning was a stranger to sentimental self-reflection. therefore as the most modern of the times. In his day, his wife Elizabeth Barrett Browning was a long time more popular. More notable female poets were Emily Brontë, best known for the novel “Wuthering Heights” (1847; “Blown”, “Storm Winds” or “Staggering Heights”), and Christina Rossetti, sister of the bald and painter DG Rossetti, one of the prerafaelites. He and AC Swinburne were among those who rose in life and poetry to Victorian standards.

The essence of the Romantic period gave way to a more social, socially critical prose. Intense criticism of irresponsibility and “mammonism” was made by the Scots Thomas Carlyle and by John Ruskin in his later, socialist phase. Most famous was Ruskin as inspiring although quite dogmatic art critic. The loner William Morris, a.k.a. poet, was one of the pioneers of organized socialism. Matthew Arnold abandoned poetry for far-sighted social criticism, e.g. in “Culture and Anarchy” (1869). JS Mill addressed women’s issues in “The Subjection of Women” (1869; “The Woman’s Subordinate Position”) and analyzed the relationships of individual-society in “On Liberty” (1859; “On Freedom”).

The last decades were marked, among other things. of continued preoccupation with religious issues, of more challenging criticism of the existing, and as an antipole of imperial patriotism. Realistic regionalism broke into idyllic. Novels about the lives of the lower classes became a significant feature.

Intense religious poetry was written by Francis Thompson and GM Hopkins, whose experiments with rhythms and word choices were unlike anything else in British poetry of the century.

Thomas Hardy, one of the great names in British poetry, began writing poetry seriously only after he had stopped writing novels after the narrow criticism of “Jude the Obscure” (1895; “Jude Fawley”). As a novelist, Hardy was a regionalist (Wessex) but primarily a pessimistic view of the destiny of man’s lot.

Empire patriotism (jingoism) was represented in poetry by e.g. WE Henley and by Rudyard Kipling in his swinging soldier songs from India, “Barrack-Room Ballads” (1892; “Soldier songs and other poems”). Less time-bound are his more serious poems and prose works, especially the novels. Another of the popular writers of the time, RL Stevenson, as well as Kipling, produced himself as a proseist for both youth and adults and as a poet.

Relentless criticism of Victorian values delivered Samuel Butler in “The Way of All Flesh” (posthumous publisher 1903; “The Path of All Mortals”) and in the witty allegorical story “Erewhon” (ie, “nowhere”, 1872; “The Land of Nowhere”). During the 1890’s, “The Naughty Nineties”, Oscar Wilde and the aesthetic circle around him, primarily the writer and illustrator Aubrey Beardsley, stood in opposition to the establishment.

About the lives of the lower classes, productive George Gissing wrote, for example. in “The Nether World” (1889), Arthur Morrison in “A Child of the Jago” (1896; “One Street Child”), Israel Zangwill in “Children of the Ghetto: A Study of a Peculiar People” (1892; ” Ghetton’s children ”) and the Irish-born George Moore with“ Esther Waters ”(1894), the truly French-inspired naturalist before 1900.

After 1900

Two great foreign writers, both naturalized British, completed and began their romance around the turn of the century: Henry James and Joseph Conrad. James’s sophisticated novels about his contemporary show a strong awareness of a rapidly changing civilization, while Conrad’s work is permeated by a critique of civilization with strong moral force, especially in the long-running novel “Heart of Darkness” (1902; “The Heart of Darkness”) and in the novel ” Nostromo ”(1904) with their fresh criticism of Western imperialism.

The period up to the 1920’s in British novel art meant a development towards greater variety and complexity both in terms of technology and content. At the same time as writers such as Arnold Bennett and John Galsworthy continued to produce novels in the traditional realistic style, influenced by, among other things. Zola and Turgenjev, a new formal consciousness was developed, in part thanks to the influence of Henry James’s novels and his “Art of Fiction” (1884). Inspired not only by James but also by Bergson’s psychology and the art of post-impressionists, Virginia Woolf wrote novels such as “Mrs. Dalloway” (1925), where with a subtle inner monologue technique and a poetic language sought to describe the self’s experience of the present.

The First World War left its mark, but not in the form of major war novels, but in a more subtle way. Already in the work of Virginia Woolf and her contemporary EM Forster, there was a clear undertone of despair, which had its origin in the liberal western man’s sense of powerlessness in the face of the tendencies of modern civilization. This became even more evident in writers such as Aldous Huxley and Evelyn Waugh, in whose novels the total cynicism is very close. A completely opposite reaction was encountered at DH Lawrence, which in opposition to oppressive conventions and inspired by, among other things. Opposites such as Tolstoy and Nietzsche sought to find and shape a whole new sense of life.

Common to all the innovators in the novel was partly a new time consciousness, where time was seen as a continuous flow within the individual’s consciousness, and partly a new view of the human psyche and its complexity, to some extent influenced by psychoanalysts such as Freud and Jung, but also by others. novelist like Proust. The emphasis of the new novel was increasingly on the relationships of the individual individuals and on their inability to truly communicate. Their consciousness flow was often portrayed in the form of various variations of the inner monologue.

The increased political awareness that the 1930’s events brought to Europe led to dystopias such as Huxley’s “Brave New World” (1932; “You Great New World”) and George Orwell’s “Nineteen Eighty-Four” (1949; “1984”).) – as well as his political satire “Animal Farm” (1945; “The Animal Farm”) – was created and won international reputation. The experiences of the war years, especially the bombings of London, were portrayed memorably in novels and short stories by Elizabeth Bowen. The desire to experiment with the novel form remained in Samuel Beckett’s monologue novels, e.g. “Murphy” (1938), and in Lawrence Durrell’s “The Alexandria Quartet” (1957-60; “The Alexandria Quartet”), an attempt to apply Einstein’s theory of relativity to the design of human relationships.

The number and variety of female writers who won a position during the post-war period is impressive. There, for example, Iris Murdoch with his morally philosophically substantiated novels, Muriel Spark with his coolly ironic intrigue, Nobel Laureate Doris Lessing with his strong political and feminist commitment, who received both a formal and content striking expression in “The Golden Notebook” (1962; “The Fifth Truth”), Jean Rhys with his suggestive modern version of Jane Eyre in “Wide Sargasso Sea” (1966; “The First Wife”) and Margaret Drabble with her analyzes of the condition in England of today.

In post-war novelists, there is a marked tendency to use imagination and allegory, not only as in JRR Tolkien’s novels, but also as William Golding did in “Lord of the Flies” (1954; “Lord of the Flies”), where in the form of the adventure story he created a frightening allegory about the rise of political evil. Graham Green’s depictions of environments and situations that later came to be at the center of politics and a clear return to realism, e.g. in Alan Sillitoes and David Storey’s novels in the working environment, belongs to the transition to the 1960’s. The university environment has also been portrayed in a series of comic-satirical novels from Kingsley Ami’s “Lucky Jim” (1954; “Happy Jim”) to David Lodge’s “Nice Work” (1988; “Nice job”).

From the 1960’s onwards, many writers devoted themselves to form experiments. One of the most noted writers of the decade was John Fowles, who in “The French Lieutenant’s Woman” (1969; “The French Lieutenant’s Woman”) combined the Victorian novel’s narrative technique with a structurally inspired view of the novel as an art product. Two other authors of the period were the hugely prolific language virtuoso Anthony Burgess and AS Byatt (Margaret Drabble’s older sister) who renewed the university novel in “Possession” (1990; “The Occupied”).

British literature has long had the ability to absorb writers from different parts of the former empire. From the 1970’s, however, it has become customary to speak of various national English-language literatures, and writers from different parts of the former empire no longer have to be established in London (or New York) before they can become internationally recognized. At the same time, there has been a marked tendency in recent decades that more and more of the writers who break through in the UK have a cosmopolitan background and are often descended from some former Commonwealth country. Nestor in this category is the Nobel laureate VS Naipaul (born in Trinidad of Indian parents but educated in Oxford), as in a series of strange novels with the action set in different parts of the world – the Caribbean, Africa, Great Britain – has dealt with the postcolonial identity problem, such as in the autobiographically inspired masterpiece “The Enigma of Arrival” (1987; “The Riddle of Arrival”).

Another well-known example is Salman Rushdie, born in Bombay and educated in Cambridge, who, with his linguistically and substantively novel art, has portrayed India’s liberation from British dominion in “Midnight’s Children” (1981; “The Midnight Children”) and the complicated cultural meeting between East and West in “The Satanic Verses” (1988; “The Satanic Verses”), whose supposedly pagan nature caused him to incur a death sentence by Iran’s then supreme leader, Ayatolla Khomeini. Other cosmopolitans include Hong Kong-born Timothy Mo, Kazuo Ishiguro, who was born in Japan, Caryl Phillips, who hails from the Caribbean, India-born Vikram Seth, Nigerian Ben Okri and Hanif Kureishi, who have Pakistani blemishes.

Even writers who cannot be included in what Mo calls the “Anglo-exotic” hem have made a significant contribution to the British novel’s technical and thematic renewal in recent decades. These include Peter Ackroyd’s gothic horror novel “Hawksmoor” (1985), Martin Ami’s settlement with Thatcherepoken’s money fixation in “Money” (1984; “Money”), Julian Barnes’s essayed reflections on the novel art in “Flaubert’s Parrot” (1984; “Flaubert’s parrot”)., Ian McEwan’s attack on modern society’s hostility in “The Child in Time” (1987; “The Time and the Child”), Graham Swift’s intricate play with the family romance in “Waterland” (1983; “Wetlands”) and the premature Angela Carter kaleidoscopically diverse “Nights at the Circus” (1984; “Circus evenings”).

McEwan, above all, has continued to consolidate his position as one of Britain’s leading writers in the early 2000’s. Among the writers who have made a name in the last few decades are Pat Barker, who in the 1990’s published his so-called so-called pacifist trilogy, Jeanette Winterson who has cultivated a deeply personal fantastic, Kate Atkinson who in novels and novels demonstrated great ability as well as the savvy stylist Alan Hollinghurst who gave an intriguing portrait of Thatchereran in “The Line of Beauty” (2004; “The Line of Beauty”). A slightly younger generation belongs to Zadie Smith, whose debut novel “White Teeth” (2000; “White Teeth”) is both a comical and thought-provoking portrayal of today’s multicultural Britain.

In the English-language poetry, something of a revolution took place in the 1910’s, both technically and motivationally. In opposition to the emotionlessness and lack of precision in the expression in the earlier poetry, the imaginers with TS Hulme at the forefront began to demand a clearer, more concrete and precise imagery and a rhythmically freer verse. The result was some excellent card poems. Inspired by the newly awakened interest in John Donnes and the poetry of the “metaphysical” poets with its spirituality and intellectual complexity but also of the linguistic virtuosity and love of the French symbolists in the metropolitan motifs, continued TS Eliot, the leading figure of British modernism, a trend towards a new poetry. linguistic and formal complexity and a very special irony, which is based on rapid changes in style and perspective.

1930’s poetry marked a significant shift in position due to its strongly ideological orientation. The depression, unemployment and the rise of fascism on the continent under Hitler and Franco led to a clear direction to the left. The poetry now written by leading poets such as WH Auden, Louis MacNeice, Stephen Spender and Cecil Day-Lewis was generally modernist in form but strongly socially critical to the content. A reaction to this dry and clinically descriptive poetry came in the 1940’s with Dylan Thomas and the poets of the so-called New Apocalypse, who with his image-rich and violent language were clearly influenced by, among other things. the French surrealists. A return to a more restrained tone, often combined with a traditional bound form, came in the 1950’s with “The Movement”, whose leading poet was Philip Larkin. He criticized modernism and reconnected with the indigenous tradition, initiated by poets such as Thomas Hardy, Edward Thomas and Robert Graves, who lived somewhat further in the shadow of modernism. After Larkin’s death in 1985, Ted Hughes, known for his intense depictions of nature’s beauty and cruelty, also emerged as the husband of the recently deceased Sylvia Plath, as the leading British poet, honored with the mission aspoet laureate, hoof poet. One notable poet who is also connected to older poets such as Blake and Housman is Geoffrey Hill, whose formidable poetry often originated from violent and tragic events in English and European history.

In recent decades, London’s previously self-evident position as the capital of British poetry has weakened. It is hardly an exaggeration to say that alongside Britain’s most respected poets, Ted Hughes has come from Northern Ireland, notably the Nobel laureate Seamus Heaney and his slightly younger colleague Paul Muldoon, who, despite their domicile heritage in the Irish tradition, also in British poetry publishing and literary debate, not least as successful holders of the post of Professor of Poetry at Oxford. Several other poets with a regional connection have won an esteemed position: so Welsh RS Thomas and Tony Harrison, as well as Ted Hughes, a native of Yorkshire, have greatly contributed to the renewal of the poetic language. Even in Scotland there is a lively poetic tradition,

Poets with a regional background are also a significant feature of the generations after Heaney and Muldoon. These include Scots Don Paterson, Kathleen Jamie and Carol Ann Duffy, who in 2009 were named new poet laureate. From Yorkshire comes Simon Armitage. All write in both standard English and their respective dialects.

In conclusion, in recent decades, British poetry has been in close contact with the English-language literary tradition, but also with the poetry written in the former colonies and Commonwealth countries. Many of the most important works of the last few decades have been written by writers who are based on the masterpieces of classical English or European tradition but interpret them in the light of their own experiences.

Drama and theater

The drama was developed in the Middle Ages from the church liturgy: the worship could be illustrated with small scenes performed in Latin. From here, the step was taken to pieces in English with motifs from the Bible or saints legends and erected in the open, including. on moving wagons. Often the slope was behind this activity on special weekends. From e.g. Chester and York feel different suites of different kinds (see miracle and mystery games). Characteristic is that the biblical motifs were mixed with burlesque scenes with allusions to contemporary conditions. This also applied to the late medieval morality plays with their personalized virtues and vices, where man is placed between good and evil powers (see Envar). The comic tradition was continued in the early twudist era’s lust for play by primarily Nicholas Udall. Classics such as Plautus and Seneca were erected or imitated at the universities and colleges. The first tragedy in blank verse, “The Tragedy of Gorboduc” (1561) by Thomas Norton and Thomas Sackville, was played, among others. at the court of Elizabeth I.

From about 1580 the theater life in London got a boost. The court organized the conduct, and nobles procured prestigious troops. The whole cultural life also blossomed after the victory over the Spanish Armada in 1588. But the theater was also pulled with some loads. Pest epidemics caused disruption, the court exercised censorship and the Puritans in the city council drove the theater people out into suburbs with mixed reputation. Most theaters were placed on Bankside on the southern shore of the Thames. Earlier, they had played at the surrounding inn. In 1576 the first regular theater was built. It was followed towards the end of the century by the most famous: Globe Theater, Rose Theater and Swan Theater. The most important troops were Lord Admiral’s Men, played plays by Christopher Marlowe, and Lord Chamberlain’s Men, the latter of Jacob I established as The King’s Men. It was Shakespeare’s part of the Globe Theater. Much knowledge of theater life provides Philip Henslowe’s diaries. They played without much props but with lavish costumes on a protruding stage under the open sky. The women’s roles were performed by young boys. A few years around the turn of the 1600’s, the adult troops received competition from child actors.

The playwrights of the time had a domestic tradition to build on. They were inspired by motifs of English and Roman history, other classical writers as well as Italian novels and comedies from the Renaissance. The Italian contemporary environment also played a major role in more or less distorted form. Comedies, tragedies and chronicles were performed. The blank verse was completed by Marlowe and above all Shakespeare. Ben Jonson cultivated his special comedy of humor.

Jacob I’s first year (from 1603) was characterized by social, economic and religious problems, and the spirit of the time left traces in the drama: intrigue, fraud, studied revenge and depravation became common motives. They had not been missing from Shakespeare, who was active until about 1610, but the tone became even darker and often cynical. Among a significant number of playwrights, John Webster emerged as perhaps the greatest with his skeptical, tragic outlook on life. At the same time, however, comedies were still played.

In 1642, the Puritans closed the public theaters. When theater life resumed under Karl II, it took place under completely different forms and conditions. Already, the shakespeare group had acquired an indoor scene. This now became the rule with a large range of scenic effects. Now women were also allowed to act as actors. Two troops with royal privileges were quickly established. French influence and the reaction of the court and the higher classes to the moral of the Cromwell became decisive for the drama of the Restoration, partly in the form of a French classical, heroic, rhetorical tragedy with John Dryden as the leading name, and partly of spiritual intrigue and moral comedy (restoration comedy).), who wished to reflect the manners of the higher classes, preferably in relief against the clumsiness of the countrymen. The foremost among several practitioners were William Wycherley and William Congreve. A woman, Aphra Behn, also appeared.

In the 18th century, the courage of the light comedy continued in various forms, usually more morally chastened. It was given a special form in John Gay’s “The Beggar’s Opera” (1728; “The Beggar’s Opera”) and in the novelist Henry Fielding’s political satires for the stage, which was subject to the censorship of the time. Later, comedies were written by Oliver Goldsmith and Richard Brinsley Sheridan, e.g. “The School for Scandal” (1780; “The School of Scandal”). Noteworthy for the period is also George Lillo’s bourgeois tragedy “The London Merchant: or, The History of George Barnwell” (1731), which became style-forming on the continent. Famous actor David Garrick gave Shakespeare a real renaissance. It continued during the romance with star actors such as Sarah Siddons, Fanny Kemble and Edmund Kean.

Most of the 19th century, for the sake of drama, became a rather insignificant period. Several of the great poets, e.g. Byron, Shelley, Browning and Tennyson wrote difficult-to-play verse dramas. Most flourished bourgeois melodrama, represented by DW Jerrold. Refreshing witty satire over Victorian values gave WS Gilbert in his and Arthur Sullivan’s operettas, the so-called Savoy Operas, eg. “HMS Pinafore” (1878). Well-made plays with discussion of time problems were written by HA Jones and the yet-to-be played Arthur Wing Pinero, but they lacked spirit and real commitment and were overpowered by George Bernard Shaw, who debuted in the 1890’s. This decade also includes Oscar Wilde’s witty and satirical comedies. For the latter part of the century are the great actors Ellen Terry and Henry Irving,

The 1900’s and 2000’s

The leading British playwright at the beginning of the last century was George Bernard Shaw, who dominated the London scenes with his discussion plays, combining a spiritual dialogue in Wilde’s sequel with a social criticism inspired by Ibsen’s plays. Social problems were also at the center of eg. Galsworthy’s more traditional drama. The Scottish-born JM Barrie gained popularity with “Peter Pan” (1904) and a couple of spiritual comedies. The turn of the century also meant a radical rebirth of the Irish drama; see Ireland (Drama and Theater).

TS Eliot contributed to a renewal of the ritual religious drama with “Murder in the Cathedral” (1935; “The Murder in the Cathedral”). His later attempts to combine religious issues with salon comedy, which in “The Family Reunion” (1939; “The Family Meeting”) had some success but did not lead to any success except possibly in Christopher Fry’s plays (eg “The Lady’s Not for Burning ”, 1949).

It was not until the late 1950’s that a renewal of the theater began, which can be compared to the revolution that had taken place within the novel and poetry at the turn of the century. It began when Samuel Beckett’s “Waiting for Godot” had its London premiere in the fall of 1955 and was followed by John Osborne’s “Look back in anger” (“See you in anger”) set up in 1956 at the Royal Court Theater, one of the theaters mainly associated with this renewal.

Becket’s “Godot” completely broke with the West End Theater conventions by presenting a couple of trifles as protagonists. With its multifaceted dialogue, the play embodies an existential problem at the same time as it gives room for a comic, which goes back to the music hall tradition.

Osborne, who represented angry young men, broke the tradition of “Look back in indicates” by portraying helpless middle-class young people who fiercely attack each other, their relatives and society in a language that shocked audiences with their gravity.

Symptoms of a creative renewal included Joan Littlewood’s experimental Theater Workshop, where Brendan Behan’s “The Quare Fellow” (1959; “The Dead Man”) and Shelagh Delaney’s “A Taste of Honey” (1958; “A Scent of Honey”) were set up.

Another innovator within the theater at this time was Arnold Wesker, who in a trilogy initiated with “Chicken Soup with Barley” (1958; “Chicken Soup with Barley Grain”) portrayed workers and their environment in a way that brought true respect and sympathy. Harold Pinter, East End Jew like Wesker, wrote more in Beckett’s absurd spirit and created in “The Birthday Party” (1958; “The Birthday Party”) and “The Homecoming” (1965; “Homecoming”) plays filled with threats and misunderstandings.

Among pregnant younger theatrical profiles is Tom Stoppard, who struck in 1966 with the original “Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead”, a comedy in which the action in “Hamlet” is seen from Hamlet’s undercutting perspective, which gives rise to both great comic and existential insight. The following year, Alan Ayckbourn, who made a successful debut with a long line of comedies, debuted with an increasingly serious undertone.

In the 1970’s and 1980’s, a number of socially critical plays, which attacked the capitalist system, were produced by writers such as Edward Bond, David Hare and Caryll Churchill. The most significant British playwright during this time, however, was Northern Irishman Brian Friel, who in plays such as “Translations” (1981) and “Dancing at Lughnasa” (1990) highlights and questions the inherited prejudices that lie behind Ireland’s conflict-ridden contemporary history.

An overview of British contemporary drama would be incomplete if it also did not include the drama written specifically for television, not only by writers such as Pinter and Stoppard, but by TV media specialists such as Alan Bennett with “An Englishman Abroad” (1985) and Dennis Potter, who with “Pennies from Heaven” (1978) and “The Singing Detective” (1986) created original works.

The influential Royal Shakespeare Company for many years left London in the 1990’s and established itself in Stratford-upon-Avon. Prior to that, it had educated a long line of brilliant directors, of whom the versatile Trevor Nunn may have been most successful, at Shakespeare as well as in the modern musical world.

What was new in the British turn of the century theater was otherwise the aggressive political trend of some young playwrights who came to be called “in-year-face”, based on a raw and dark view of society and an attack filled with attack. Most notably, it was expressed by Sarah Kane (“Blasted”, 1997) and Mark Ravenhill (“Shopping and fucking”, 1995). Kane’s suicide prematurely became a symbol of a completely illusionless generation. In return for a slightly different and perhaps brighter view of society, the more traditional playwright Simon Stephens replied. British political drama has lived on in different forms through older names such as David Hare, Alan Bennet and Caryl Churchill.

During the first year of the 21st century, the commercial theater in the West End has undergone a structural transformation through change of ownership, which has reinforced the dominance of musicals. The more artistic theater is concentrated on the flagship National Theater and on the Royal Court, which continues its focus on new dramas, as well as a smaller number of “Off-WE” scenes, of which Donmar Warehouse can be mentioned. A growing interest in foreign drama has been noticed in recent years. The fundamental vitality and pace of work in British theater remains, as does its sense of tradition. One expression of the latter is the re-creation, certainly through American initiatives, of Shakespeare’s The Globe, roughly at the historic site on Bankside where the original once lay. There, both tourists and Britons in a carefully restored environment can experience high-level theater,

Film

Britain’s first contribution to the film as art was the Brighton School, operating from 1897 with James Williamson (1855–1933) and George Albert Smith (1864–1959) as well-known representatives. Both developed the cutting technique in a way that influenced other filmmakers, e.g. in films such as Williamson’s “Attack on a Chinese Mission Station” (1900) and Smith’s “Mary Jane’s Mishap” (1902). Another early classic was Cecil Hepworth’s “Rescued by Rover” (1905). However, the early British silent film faded in competition from mainly France, Italy and the United States.

The most important artistic name in British film during the silent film era was Alfred Hitchcock, who directed the British feature film’s first masterpiece “The Lodger” (1926), a dense thriller that showcased the typical ingredients that later made Hitchcock one of history’s most esteemed and rewritten filmmakers. It was also Hitchcock who, with “Blackmail” (1929), developed the sound film aesthetic.

An important British film tradition in the 1930’s was the documentary film, led by the socialist Scotsman John Grierson, who wanted to change society with the help of socially engaged films. Grierson himself made his debut with “Drifters” (1929), a film about fishermen in East Anglia, and with financial support from the British Post Office he mentored a number of talented documentary filmmakers, eg. Edgar Anstey (1907–87) and Arthur Elton (1906–73) with “Housing Problems” (1935) and Harry Watt (1906–87) and Basil Wright (1907–87) with “Night Mail” (1936). The British feature film during the 1930’s was largely dominated by Alexander Korda’s productions, eg. “The Women Around the King” (1933).

One of the great times of the British film came during the Second World War. Both documentary and feature films were mobilized in the nation’s struggle. The documentary influence was evident in war film classics such as Noel Coward’s and David Lean’s “The Sea Is Our Destiny” (1942). The British propaganda film during the war culminated with Laurence Olivier’s symbolic victory vision in Shakespeare’s “Henrik V” (1945). An extremely fruitful artistic collaboration took shape during the war between Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger. led to the grand ballet film “The Red Shoes” (1948).

After competing out of Hollywood both abroad and in the domestic market in the late 1940’s, the British film in the 1950’s and 1960’s was characterized by new trends. The so-called Ealing comedy named after Michael Balcon’s company, with films such as Alexander Mackendrick’s “Ladykillers” (1955), flourished in the early 1950’s. In the wake of the rising welfare state, however, demands were made for a film art that portrayed the working class and the conditions of the youth. The so-called sink realism, akin to the young men’s dreams and novels during the period, obeyed the demands of films such as Karel Reisz’s “Saturday Night and Sunday Morning” (1960) and Tony Richardson’s “A Scent of Honey” (1961).

The youth revolt, in turn, got one of its prime expressions in Lindsay Anderson’s “If…” (1968), a fantasy film about a violent revolt at a British private school. However, many of the leading personalities of the 1960’s, as the top talent in the British film industry always tended to do, continued their careers in Hollywood. One who remained in the UK was the Trotskyist director Ken Loach, who with a number of well-known documentaries and, above all, the supremely realistic feature film “Kes – falken” (1969) laid the foundation for a periodically successful career. Another influential film artist in the 1970’s was Ken Russell, as with visually grandiose, but according to several observers baroque artworks, e.g. the cruel Aldous Huxley filmization “The Devils – the Devils” (1971) and the musical “Tommy” (1975), created extensive critical debate.

In the 1980’s, the British film experienced yet another heyday, with both major audience successes, such as Hugh Hudsons (born 1936) “The Moment of Triumph” (1981) and Richard Attenborough’s “Gandhi” (1982), and artistic success with films by. Terence Davies (born 1945), Stephen Frears, Peter Greenaway and Derek Jarman. Worth mentioning are also the British filmmakers who during the period achieved great success in the American film industry, for example. Nicholas Roeg, John Boorman, Alan Parker, Adrian Lyne and brothers Ridley Scott and Tony Scott. However, after the state film subsidy ceased in the mid-1980’s, the British film industry was more or less thinning away. Most of today’s film productions are largely financed by British or foreign broadcasters.

However, with these TV-financed, internationally low-budget films, the British had success in the 1990’s, both in purely economic terms and in terms of critical prestige. Neil Jordan’s film “The Crying Game” (1992), a suggestive thriller with homoerotic motifs, became an unexpected audience success in the United States. Similarly, Danny Boyle’s fantasy-rich thriller “Trainspotting” (1996) and Peter Cattaneos (born 1964)) “All or Nothing” (1997), a film that skilfully blended the tradition of Ealingkomedin with the countertop realism, huge financial successes compared to the relatively modest investments. The Shakespeare Films, a UK-acclaimed genre, experienced a tangible renaissance with films created by director and actor Kenneth Branagh, for example. “Henrik V” (1989) and “Very essence for nothing” (1993).

During the 1990’s, British film production gradually increased in scope, from 46 films in 1991 to 116 films in 1997. Measures taken to stimulate film production, including tax relief, promises good for the future; however, distribution continues to be the major problem for British film.

In 2000, direct government support for film production returned in the form of the establishment of the UK Film Council. Through this support and by being able to distribute their films in three stages – cinema, DVD, TV viewing – British film production has been able to continue.

The films during the 2000’s largely borrowed their expression from the political protests of the 1980’s. For example, a tough and form-proof social realism characterizes Mike Leigh’s “Vera Drake” (2004), a poignant film about a woman who performs illegal abortions, while the more imaginative and modernist influenced in the 1980’s flume culture is expressed in Danny Boyle’s “Slumdog Millionaire” (2008). Another feature of the 21st century is lavish films about historical figures in the style of Shekhar Kapurs (born 1945) “Elizabeth – The Golden Age” (2007), the sequel to the director’s previous success “Elizabeth” (1998), or Stephen Frears “The Queen ”(2006), with an acclaimed actor performance by Helen Mirrenin the role of the current queen. Another successful royal-related film was Tom Hooper’s (born 1972) “The King’s Speach” (2010), in which Colin Firth was awarded the Oscars for his portrayal of the staggering King Georg VI.

The British animation studio Aardman Animations has reached world reputation with its clay animation since the 1990’s.

Through several artistic successes in the domestic market, British film culture has gradually been strengthened, which in turn has led to increased state investment in film. In 2010, 79 feature films were produced in the UK with domestic funding.

Photography

Many of the pioneering photo-technical inventions have been made by Britons, but the British photo industry has still had a stubborn existence internationally. Success has been significantly greater on the pictorial level. Photographers such as David Octavius Hill, Henry Peach Robinson, Oscar Gustav Rejlander and Julia Margaret Cameron were active in the mid-1800’s and have gained world-renown in artistic photography.

The Royal Photographic Society (founded in 1853 by Roger Fenton) worked early on to get photography recognized as an artistic means of expression. Many of the artistically oriented members formed the break-out group The Linked Ring in 1892. The London Salon (first opened in 1910) was for many years the most important international photo exhibition, and the impressionistic pictorial style called pictorialism, whose cradle stood at the turn of the century, was long cherished in Britain. The style was reflected in the yearbook “Photograms of the Year”, and over time British exhibition photography came to appear increasingly conservative.

Picture magazines such as Illustrated and Picture Post started in the 1930’s and provided space for a vital reportage photography with photographers such as Bert Hardy, Kurt Hutton and Bill Brandt. During the 1960’s, the British daily newspapers’ Sunday annexes came to serve as a platform for a younger and more radical photography generation with, among other things, Don McCullin and Philip Jones Griffiths as important profiles. Cecil Beaton and David Bailey are well-known in fashion photography. In addition, both are, like Antony Armstrong-Jones, highly regarded portraits.

Art

The visual arts in England begin in the religious book painting that, after an Irish model, developed in Northumberland in the 6th century. Later around the great cathedrals arose print and illustrator studios, scriptories, in York, Saint Albans, Winchester and Canterbury. Characteristic of the miniature painting during the 13th and 1300’s is a fabulous storytelling delight that blends folk life depictions, babwyneries, into the church texts.

Henry VIII ‘s church reform in 1534 and the dissolution of the monasteries in 1536 meant that the church art ceased for a long time in England. Up to the flowering period of landscape art in the 18th century, the secularized visual art was dominated by the portrait painting, with two immigrant artists, Hans Holbein dy and Anthonis van Dyck, as the lively name. The German-born Holbein, who was also well acquainted with Italian and French contemporary art, spent two periods in England (1526-28 and 1532 until his death in 1543) and became the official court painter of Henry VIII.. Holbein’s meticulous and detailed, sober yet elegant and brilliant portrait art became the first highlight of the painting in England. He also performed portrait miniatures, a genre that with great imagination was further developed by Nicholas Hilliard in finely tuned portrayals of royalty and members of the nobility during the time of Elizabeth I and Jacob I.

A distinctive, manneristic portrait painting was practiced by native English painters, while Jacob I’s painting, Anna of Denmark, promoted the visual arts at the theater in Inigo Jones masques, the court’s dance and song performances. But it was not until 1532, when Karl I convinced the 33-year-old Flemish-born van Dyck to settle in England, the visual arts there gained their next period of brilliance. He had performed extremely elegant depictions of the nobility of Genoa; now he refined his imagery further in his often slightly melancholic, distinguished English portraits. Here are also the first examples of the landscape as a mood-creating resonance ground for the portrait of the great landowners.

The 18th century is the great century of English-born portrait painters. Academic Joshua Reynolds finds a classifying tendency, with quotations by Michelangelo and Rafael, alongside an interest in Rembrandt’s passionate painting, while his contemporary Thomas Gainsborough is more independent of the great continental style. Gainsborough’s portraits are distinguished by their natural charm, while the cultivated land occupies a prominent place in some of his images of the country estate. He also performed atmospheric saturated landscapes dating back to Dutch painting.

A British specialty is the sporting picture, as well as the often genre-specific group portrait, the conversation piece. Highly anecdotal, often solidly moralizing, is William Hogarth, whose picture suits were multiplied and spread throughout Europe in the form of copper engravings. Sober observation of animals and people in symbiotic cohabitation is expressed in George Stubbs’ pictures of horses and dogs, of hunting and sports among the landlords. Also among the portrait painters is Alan Ramsay, Scotland’s first prominent visual artist.

Of importance to the development of European art became the theory and practice of landscape painting in S., not least in the watercolor art, which in the 18th century was represented by Alexander and Robert Cozens, Francis Towne, John Crome and Thomas Girtin, later by John Constable, William Turner and Richard Parkes Bonington. The transparency of the watercolor airily reflected the distinctive character of the landscape, while William Blake’s gothic watercolors gave the character to humanity. His religious art influenced Samuel Palmer, who in the 1820’s in his landscape watercolors elicited a mysterious nature ecstasy. The British landscape painting with Constable’s lyrical portrayal of reality and Turner’s almost abstract visions of fog, light and colors also gained influence on the French painting art during late Romanticism.

The inclination for satire in British art was further conveyed from Hogarth’s depictions of James Gillray’s and Thomas Rowlandson’s satirical images. A socially critical tendency is also found in much of the 19th century genre paintings with carefully rendered costumes and interiors. The artist group Prerafaelites went back to the Italian quattrocento painting to find an original, ethically sustainable expression. Influenced by John Ruskin, they tried to create realistic religious images and medieval scenes with meticulous modes of expression. The group included Ford Madox Brown, Holman Hunt and John Everett Millais. William Morris sought to realize a socialist dream of fine art for all and ingenious craftsmanship instead of industrious industrial products.

At the turn of the 1900’s, the beauty cult of the Prerafaelites became decadent aesthetic, exemplified by the elegant line play in Aubrey Beardsley’s illustrations. Talented book artists were Arthur Rackham and William Nicholson, while Kate Greenaway and Beatrix Potter created a prominence for the English children’s book.

The visual arts in Britain followed in the 20th century without much independence the continent’s innovation in its tracks. However, a distinctive religious painting meets Stanley Spencer, and the immigrant German painter Frank Auerbach occupies his own position with his very pastosa painting. After World War II, Britain’s most prominent painter was the dramatic Francis Bacon, while Ben Nicholson’s abstract images are characterized by a delicate beauty. Significant sculptors were Henry Moore and Barbara Hepworth, while pop artists Richard Hamilton, Peter Blake and, in particular, David Hockney had a certain influence on the painting’s return to the object-centered and depicting circa 1960. The British sense of the landscape as cultural phenomena and bearers of state of mind lies behind Richard Longs land art, geometric figures (often stonework) in nature.

The sculptor Richard Wilson had his first solo exhibition in London in 1976 and during the 1980’s made his big breakthrough. Today, he is a world name known for his spectacular site-specific works where play with spatial illusions plays a big role. During the 1980’s, the duo Gilbert & George also came to an advanced position in contemporary art, partly with performance works and partly with astonishing photo-based works in clear colors, sometimes with homoerotic elements.

At the end of the 1980’s, a new generation of artists emerged that would dominate in the 1990’s: Young British Artists revitalized the British art scene through a series of controversial works that are still being debated. Some of the top names are Damien Hirst, Gillian Wearing and Tracey Emin. Characteristic of these artists is the combination of entrepreneurship and rebel attitude. Several of them have achieved some kind of rock star status.

The prestigious Turner Prize has become one of the most regarded awards for contemporary art but also the subject of recurring controversy. In 2010, the award was given to Susan Philipsz from Scotland, which was the first time she went to an audio artist. Philipsz’s art is centered around folk songs, and in the installation “Lowlands Away” she sings different versions of a Scottish lament from the 16th century. On the whole, the Scottish art scene has attracted great interest internationally in recent decades. The Edinburgh-born artist Peter Doig, with his figurative painting, has become one of the most highly regarded names in contemporary art.

Crafts

In the old British art of furniture, it was put practical and comfortable before the fashionable. Great demands were also placed on the quality of the material and the craftsmanship. Characteristic was the attraction to Gothic, a style that was never really abandoned; e.g. 18th-century Chip Valley furniture is largely based on Gothic motifs. The interest in the material meant that certain types of wood were favored, which greatly affected the design of the furniture and also formed the basis for a period breakdown; The period from the mid-17th century to about 1730 is thus called the walnut period, the later part of the 18th century satin tree period. And when other furniture was gilded in other countries, the British instead took advantage of the natural wood’s structure and effect. The propensity to let the need control the development led to the launch of new furniture types; inter alia is the bookcase and the writing office British innovations. Another expression of the focus on the functional was the combination furniture, which, however, sometimes appeared more sensible than useful.

Its climax reached the national British style of furniture during the second half of the 18th century, through Chippendale and above all through Robert Adam, whose refined classicism was passed on by Hepplewhite and Sheraton. The style spread through pattern books and became of decisive importance for the art of furniture on the continent and in the Nordic countries. The same high level held other branches of the arts, and here too the British stood to a large extent as a rewarding party. This was especially true in the field of technology; in the glass art, George Ravenscroft introduced the crystal glass in the 1670’s, and a century later Wedgwood’s flintgoods began their victory train across Europe.

See also Edwardian style, Georgian style, Jacob I’s style, Stuart style and Tudor style.

Modern crafts

Around 1860, a revival of the arts and crafts started in the United Kingdom, updated after the London Exhibition in 1851, when the critics were upset over the ugliness and poor quality of the machine-made goods. William Morris became the central figure in a new movement which, with inspiration in the Middle Ages, propagated for good craftsmanship, genuine materials and authentic form. His work and ideas were further developed by the Arts and Crafts Movement, whose ideals strongly influenced the European contemporary world.

Modernism got no expression in British design, with the exception of Omega Workshops, founded in 1913 by Roger Fry and formed a branch of the Bloomsbury Group. Significant in contemporary ceramics was Bernard Leach, who in 1920 founded a workshop in Saint Ives in Cornwall, where he collaborated with Shoji Hamada. Within the typography, Eric Gill, Stanley Morison and the German-born Jan Tschichold.

In 1943 Gordon Russell started “Utility Furniture”, a social furniture project, simple designed furniture with good quality at low prices. The exhibition “Festival of Britain” (1951) introduced modern British design on a larger scale, and with the 1960’s pop fashionthis gained a brief world reputation. A Scandinavian embossed, everyday design broke through with Terence Conran’s Habitat stores on a broad front during the 1970’s. Kenneth Grange and David Mellor are among the leading industrial designers of the time. During the 1980’s, some furniture designers attracted international attention, including Jasper Morrison with minimalist furniture and Ron Arad and Danny Lane with brutalist chair sculptures in sheet metal and jagged glass. Designers today include Ross Lovegrove, who gives high-tech industrial design a sensual and organic design language.

Architecture

From the Roman period of the United Kingdom, numerous remnants of plants and buildings remain, including of Hadrian’s Wall and of Baths in Bath. The street networks in many cities also have Roman ancestry. The oldest churches (600-100’s) belong to the Anglo-Saxon architecture: a basically Romanesque building style, consisting of small buildings in roughly cut stone with narrow, arched doors and windows. Characteristic features are band patterns and towers with coupled, round arched openings. More than 400 churches with masonry from this period are preserved, among others. in Bradford-on-Avon, Brixworth and Earls Barton. There is also a wooden church, the stake church in Greensted. A more advanced Romanesque architecture was introduced from the 1070’s by the Norman conquerors, who erected a large number of magnificent church buildings. Among the most prominent are the cathedrals of Ely, Norwich, Peterborough and Durham; the latter the most uniform of them all. The Norman style is characterized by powerful pillars, richly profiled round arched openings and massive walls. Already there are many of the typical features of the British cathedrals: elongated buildings with long cows, the crisscross and the fairly unoccupied west facade. Another important type of buildings were the bailouts. The first one in stone was the White Tower in London. Colchester and Rochester. Another important type of buildings were the bailouts. The first one in stone was the White Tower in London. Colchester and Rochester. Another important type of buildings were the bailouts. The first one in stone was the White Tower in London. Colchester and Rochester.

In 1175, the French Gothic was introduced when a new choir was erected at the Cathedral in Canterbury. Ten years later, in the Cathedral in Wells, a more English young Gothic, early English, appeared with a horizontal structure, low sitting arches and high, simple pointed arch windows. The High Gothic (c. 1250–1375) is called in the United Kingdom decorated style. Arches, windows and sculptural details during this period became an increasingly richer, more decorative design. The final phase of the Gothic, perpendicular style, is a distinctive English style, which appeared from about 1330 to the beginning of the 16th century. The most uniform buildings of this time are King’s College Chapel in Cambridge and Bath Abbey, but many cathedrals were also built at the same time. The buildings consisted of thin skeleton structures with a considerable height endeavor, large windows and very rich arch forms: net arches, solar arches and, at the beginning of the 16th century, arches with suspended end stones, so-called pendants.

After the Reformation, the kings and aristocracy took over the role of the foremost builders. Many large castle facilities – i.a. Longleat House (1572), Hardwick Hall (1591) and Audley End (1603) – now erected in Elizabethan style; a renaissance characterized by lingering medieval features. In the 1610’s, Inigo Jones introduced an Italian renaissance in Palladio’s tradition, and for a few hundred years a strict classicism came to dominate Britain’s architecture. Baroque features can be found in the late 17th century leading architect Christopher Wren, with Saint Paul’s Cathedral in London as the most famous building. In his aftermath, John Vanbrugh and Nicholas Hawksmoor appeared.

The period 1714-1830 is known as Georgian style. Typical of this are site formations, squares, surrounded by so-called terrace-houses(townhouse type house) in a restrained classicism. Many such formations are found in London and other cities. In some cases, entire neighborhoods were built in the style, the best known in Bath (1720’s) and Edinburgh (1767). With the romance of the middle of the 18th century, interest in the Middle Ages, the Orient and China flourished. Its main expression was this in the so-called English park, where small exotic buildings of different styles were blown up. In Britain, however, the gothic had never really died out; also Wren, Hawksmoor and other leading architects used Gothic forms in various contexts. In the years 1753-76, the leading socialite Horace Walpole had “Gothized” his home of Strawberry Hill, and towards the end of the century, architects like James Wyatt and John Nash built in both gothic and other styles.

The period 1837–1901 is called Victorian style and is especially associated with all new styles that came into use during the expansive late 19th century. Many churches – especially in neo-Gothics – were built, as were public buildings such as schools, museums and administration rooms. International significance for the housing architecture gained some directions that drew its inspiration from older indigenous architecture: the Arts and Crafts Movement, which was based on popular building art with roots in the Middle Ages and which emphasized the craftsmanship and genuine materials, and the Queen Anne Revival, which built on the early 1700’s century’s brick architecture.

In the field of “engineering architecture”, Britain was a pioneer. The world’s first major iron bridge, Ironbridge, was built in 1776–79; railway stations were built from the 1830’s and the glass and cast iron building Crystal Palace was created for the London exhibition in 1851. In 1890 the Forth Bridge (see the Forth bridges) was opened outside Edinburgh, one of the “seven wonders” of industrialism. Also included in the architecture of industrialism were grand factory buildings and entire industrial societies, for example. the New Lanark design community south of Glasgow, founded in 1785 (see Robert Owen).

During the first decades of the 20th century, the classicist tradition re-emerged, especially in the large-scale buildings of the city for commercial use. In the more small-scale housing development, the popular building tradition was an important source of inspiration. Early functionalism played a very hidden role; only after the Second World War was a modernist architecture built to a greater extent. Buildings such as the Royal Festival Hall in London and the new Cathedral in Coventry were erected in flooded areas. New towns were built around London and other major cities, and in London’s metropolitan area, high-rise buildings began to grow. City renovations and demolitions have had a relatively limited scope; Instead, public pressure has led to investment in building maintenance and upgrading of old city centers. The structural changes during the post-war period created major problems for port and industrial areas, and in the 1980’s several very extensive renewal projects were started, mainly with postmodernist architecture, but also where older buildings and facilities were sought. The best known of these projects is the London Docklands.

LANDSCAPE-GARDENING

Britain’s earliest known gardens came with Roman-era villas. During the Middle Ages, with the monasteries as a holding point, there was a lively exchange of seeds and plants inside and outside the country. Important influences came from the rich Islamic garden culture in southern Italy and from Sicily, conquered by the Normans. Britain’s gardens during the first half of the 16th century differed from contemporary ones by the amount of grassy areas, grants painted wooden ornaments and built-up hills. Particles with intricate hedge patterns were built adjacent to buildings to be viewed from above.

Even in the 1600’s, English garden art was heavily influenced by foreign models, first French Baroque and later, through William III, Dutch style with small, tufted garden rooms. In the 18th century, Britain took a leading position in European garden art through the development of the landscape park (see English park). Influential theorists were the poets Alexander Pope and William Shenstone. Wealthy amateurs, during lively exchanges of thought, created idealized landscapes with scattered structures. A special variant was ferme ornée, idealized farm (see picture Liselund). The landscape style was developed formally by Lancelot (“Capability”) Brown. One reaction to his many parks, characterized by sweeping grasslands, scattered tree groves and winding streams, was the picturesque, which sought a lost impression. This also shows the increasing appreciation of the beauty of the wild landscape at the end of the 18th century. Gradually, a return to formal style took place. Humphry Repton let terraces mediate the transition between buildings and landscape parks.

During the first half of the 19th century, the New Renaissance and New Baroque became popular styles by the leading architects Charles Barry and William Nesfield. These gardens were well suited to expose the floral splendor made possible by improved greenhouse technology and long-distance plant transport. The gardenesque style, entirely focused on showy floral arrangements, was developed by JC Loudon, who also spread the garden interest to wider peoples. The fight for finer flower compositions was led by William Robinson, influenced by the Arts and Crafts movement’s quest for authenticity. The style was perfected by Gertrude Jekyll and Edwin Lutyens. It lived for a long time in the UK, represented by Russell Page. Modernist style features were introduced in the 1930’s by a.k.a. Christoffer Tunnard and Geoffrey Jellicoe.

Music

The oldest known music in Britain is the songs of the Celtic bards. Remains of this tradition remained in Wales well into modern times. Literary and iconographic sources as well as finds of musical instruments give glimpses of the music’s life in the early Middle Ages. Among other things, remnants of lyres and harps have been found, and descriptions and depictions of the large organ with 400 barrels, which about 950 were built in Winchester Cathedral, testify to a skilled craftsmanship.

Multi-part church music is preserved from about 1000 in the Worcester Tropics, while profane music in the form of dances and a cannon was found in sources from the 13th century. Some later sources report a troubadour tradition similar to that found on the continent. A popular song form, carol, was at first a unanimous dance song with chorus fringes, but appeared from about 1400 more and more frequently in multi-part sets. Through the so-called Old Hall manuscript (c. 1420), the names of several English composers active in the latter part of the 1300’s are known. John Dunstable is the foremost English composer of the early 15th century. Several finds of his music in manuscripts on the continent show that English music spread on the continent during the centennial war.

In the 16th century, the transition to Protestantism led to a depletion of music. In the latter part of the century a recovery was made by composers such as Thomas Tallis, Thomas Morley and William Byrd. Among other things, new forms of church music were developed such as anthems with lyrics in English. The “Musica transalpina” published in 1588 with English imitations of the Italian madrigal form gained wide spread, and Thomas Weelkes and John Wilbye continued this form as a special English tradition. Solo songs for lutakompanjanang received, among other things. through editions of John Dowland’s music many practitioners.

For social use, especially among men, a type of cannon song, catch, was developed, which was practiced well into the 19th century. Collections for piano instruments such as The Fitzwilliam Virginal Book (c. 1620) also testify to highly driven playing skills among amateurs. Many stage directions at Shakespeare show the important role music played in the theater arts. The strong influence that Puritan forces had in Britain in the 17th century led to a decline in church music and hampered the rise of domestic music drama.

After the restoration in 1660, the musical elements of the spectacle increased rapidly, and from 1672 public concert forms began to be established in London. The most important composer of the late 17th century was Henry Purcell with a large production of church music and stage music. His only opera, “Dido and Aeneas” (1689), is one of the masterpieces of the era. With Handel ‘s arrival in London in 1710, the Italian opera form gained a foothold in Britain as public entertainment. Around 1725, it received competition from a domestic, more popular and comic opera, ballad opera, with John Gay’s “The Beggar’s Opera” being the first of this kind. Handel responded by developing a special British oratorical form; “Messiah” (1742) became his greatest success among the 17 oratories he composed in 1733–51. Contemporary with Handel was among other things. William Boyce and Thomas Arne. The latter’s two song collections “Lyric Harmony” (1745-46) became important prototypes for music that turned to a broad amateur musical public. Social musicianship took place, among other things. in glee clubs (compare glee), a form that lived well into the 20th century. However, the more extroverted public music life was long dominated by musicians from the continent such as JC Bach and Muzio Clementi, both operating in London during the second half of the 18th century.

During the 19th century, professional orchestras were formed in London and other major cities. In music, however, the great interest in choral music played a more important role. Choral societies were formed and a tradition was started with annual recurring major festivals, at which Constructions of Handel’s oratorios took place. Successful composers during the 19th century were the Irish John Field, Samuel Wesley (1766-1837) and his son Samuel Sebastian Wesley (1810-76), Arthur Sullivan (who did operetta in collaboration with the copywriter WS Gilbert), Hubert Parry and Charles Villiers Stanford. Edward Elgarsinfluence extended into the 20th century. In the cities had pleasure gardens, among others. Vauxhall Garden in London, with easier entertainment from outdoor scenes, became popular as early as the 18th century. From about 1850, this type of entertainment began to take place indoors in the music halls. The amateur musicianship was stimulated in brass bands, and the UK still has a leading position in this area.

The more prominent British music personalities of the early 1900’s were composers such as Frederick Delius, Arnold Bax, John Ireland, Gustav Holst, Ralph Vaughan Williams, William Walton and conductors such as Thomas Beecham and Henry Wood; the latter led the promenade concerts the Proms 1895–1944. Benjamin Britten is one of the most influential composers of the 20th century with his orchestral and chamber music, but also an extensive musical dramatic production.

Since 1950, composers such as Michael Tippett, Thea Musgrave, PM Davies, Harrison Birtwistle and Brian Ferneyhough have received attention. Conductors such as John Barbirolli, Adrian Boult and John Eliot Gardiner and singers such as Kathleen Ferrier and Peter Pearshas also had great international success. Since its inception in 1927, the BBC has been important for the music industry in the United Kingdom, but also as a role model for many European radio stations’ responsibility for folk education in the music field. During the latter part of the 20th century, the emphasis in Britain’s music life was shifted increasingly to genres with a strong commercial focus. A special British musical was developed from the 1960’s by Lionel Bart (“Oliver!”, 1960) and Andrew Lloyd Webber (with successes such as “Jesus Christ Superstar”, 1971, and “The Phantom of the Opera”, 1986).

Song is the most important means of expression in the popularly anchored music in the UK. The song heritage includes narrative songs (ballads), lyrical songs, work songs – eg. seamans’ songs (shanties) and songs created by professional groups such as miners and textile workers – as well as seasonal songs, many of which are linked to the Christmas holidays (christmas carols). The instrumental music mainly includes dance music. The most common instruments in this folk tradition are one-handed flute and drum (pipe and tabor), small-pipe (a type of bagpipe), violin, simpler forms of accordion (concertina) and harmonica.

The National Eisteddfod competition festival is organized in Wales annually since 1880 but has roots in the singing competitions that already existed during the Middle Ages. Important festivals are also organized in Glyndebourne (opera), Aldeburgh and Edinburgh (music and theater).

See also London (Cultural Life).

popular