Literature

The oldest dated text in Romanian is a letter from 1521, but no real Romanian literature emerged until the 16th century chronicles. The learned Dimitrie Cantemir was the first modern history writer. The Greek dominance of Romanian cultural life was broken as the so-called Trans-Sylvanian school in the late 1700’s began a novelization of the language and a cultural approach to Western Europe.

The 19th century began with compelling translations from French and the collection of Romanian folk poetry. In response, Mihail Kogălniceanu made a program statement for national literature, and Vasile Alecsandri emerged as a modernizer of Romanian literature. The unification of Moldova and Valakia in 1859 sparked an interest in Romanian national literature, and a little later the so-called June Movement was formed, which paid tribute to its beauty and turned to foreign influence. This group included the nationalist Mihai Eminescu and the proseist Ion Creangă, who, together with the satirical playwright Ion Luca Caragiale, begins the mature Romanian literature.

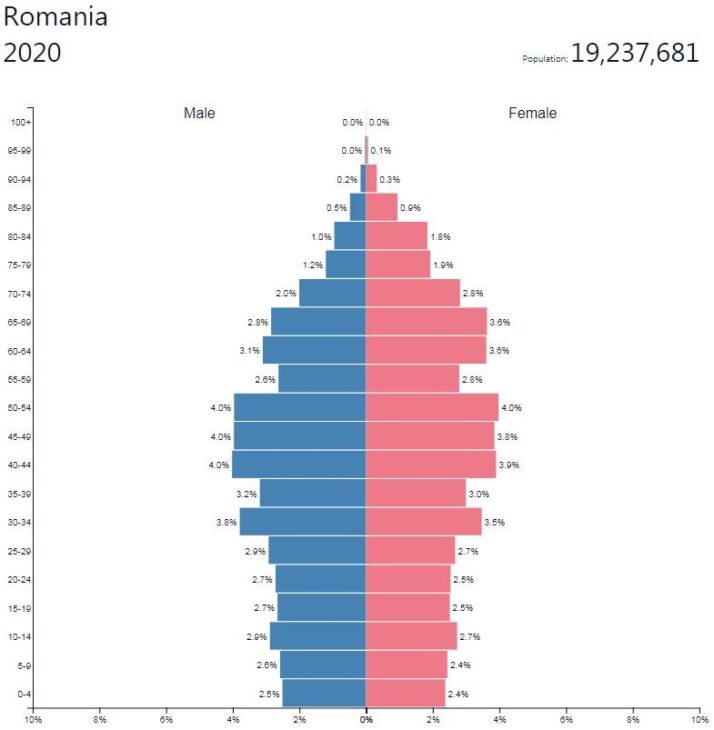

- Countryaah: Population and demographics of Romania, including population pyramid, density map, projection, data, and distribution.

At the turn of the century, a mostly conservative, patriotic direction with great interest in folk poetry and history dominated and with the historian Nicolae Iorga, the public life painter Gheorghe Coșbuc and the poet Octavian Goga as prominent figures. At the same time, Alexandru Macedonski launched a symbolist, French-inspired direction, which laid the foundation for a surrealistic literature. However, the great surrealist Eugène Ionesco left Romania, as did the prose and religious historian Mircea Eliade.

The interwar period was a literary rich era with great poets such as Lucian Blaga and Tudor Arghezi as well as epics such as Liviu Rebreanu, Mihail Sadoveanu and Zaharia Stancu. They portrayed with great realism Romania’s tumultuous growth. In the post-war era, patriotic social realism was initially written, but the colorful rural depictions lived on in Stancus and Sadoveanu’s prose. Marin Preda’s socially critical works were banned, and the relentless dissident Paul Goma’s depiction of a Romanian gulag was published in the West. The poets Ana Blandiana, Marin Sorescu and Nichita Stănescu sought new, independent forms of expression. Mircea Dinescu’s poetry discusses ethical problems and the corruption in the country.

After the cessation of the dictatorship, many writers have portrayed the disintegration of communism and dictatorship.

Drama and theater

The modern Romanian drama was created in the late 19th century by Vasile Alecsandri and Ion Luca Caragiale, whose works are often played. Later, the problems of modern society were portrayed by Aurel Baranga and Paul Everac. Since Romania became communist, i.a. Titus Popovici and Dumitru Radu Popescu on the political struggle. The poet Marin Sorescu has written personally interpreted historical dramas and also, like Radu Stanca and Horia Lovinescu, allegorical dramas with new interpretations of universal and national myths.

Film

Romanian film production before the audio film is partially obscured due to the destruction of many works, and the early film history has largely been reconstructed from still images and articles in daily press. The first native filmmaker was the neurologist Gheorghe Marinescu (1863-1938), who with a Lumière camera made a series of medical documents around the turn of the 1900’s. the 1877 uprising against the Ottoman Empire. During the 1920’s Aurel Petrescu (1897-1948) made a series of animated short films. As a whole, the fiction films were few and sporadic, most of the pre-1930 productions were journal and documentary films.

After the establishment of a national film authority in 1934, the number of productions increased, however, according to earlier patterns. The post-war period in 1948 led to the nationalization of the film industry. The Film School Institutul de artă cinematografică started training in all areas. The industry was concentrated in three state companies: for feature films, documentaries and animated films. Within the latter, Ion Popescu-Gopo reached world fame with films characterized by humanism and subtle humor, including “A Bomb Has Been Stolen” (1961).

During the 1960’s, the directors mainly noticed the directors Liviu Ciulei (1923–2011; “The Outbreak”, 1957) and Lucian Pintilie (1933–2018). In the years leading up to Ceaușescu’s case, original reggae gifts such as Dan Piţa (born 1938), Mircea Veroiu (1941-97) and Mircea Daneliuc (born 1943) emerged, all of which gained some international attention. While in Romania during the 1980’s, 25-30 feature films were produced annually during the 1990’s, annual production dropped significantly due to a lack of risk capital and investments.

In the 2000’s, a new generation of filmmakers presented themselves internationally after Cătălin Mitulescu (born 1972) won the Gold Palm in 2004 in the short film class with “Trafic” and Christian Mungiu won the award in the 2007 long film class with “4 months, 3 weeks, 2 days”.

Some films look back at the communist society, such as Corneliu Porumboius (born 1975) “12.08 East of Bucharest” (2006) and Mitulescus “How We Celebrated the Destruction of the World” (both 2006), while others critically view the new capitalist society, t.ex. Christi Puius (born 1967) “The death of Mr. Lazarescus” (2005), Porumboius “Polis, adjective” (2009) and Florin Șerbans (born 1975) Romanian-Swedish co-production “If I whistle, I whistle” (2010). Christian Mungiu has continued to be successful with “Beyond the Mountains” (2012). Călin Peter Netzer (born 1975) won the Golden Bear in Berlin 2013 with the drama “Pozitia Copilului”.

Art

Crucial to understanding Romania’s ancient art history is, on the one hand, the Byzantine traditions in Moldova and Valakiet, on the other, the close contacts with Central and Western Europe in Transylvania. The decorative art of stone, wood, metal, textile and ceramics has played a major role, and the forms live on both as folk art and in mass production. In Moldova and Valakiet, the church in the 19th century was the most dominant art commissioner and murals and icons were the most important genres.

Contemporary with the nation formation during the second half of the 19th century, it was versatile Theodor Aman, portrait and history painter and founder of the first domestic art school, in Bucharest, 1864. With Ion Andreescu and Nicolae Grigorescu, a landscape painting was developed in the aftermath of the Barbizon school. Opponent to the Academy of Fine Arts and its representatives during the early 1900’s was the painter Ștefan Luchian, embossed by the French turn of the century. Romania’s great modernist sculptor Constantin Brâncuși early became part of the Parisian avant-garde, but his starting point also belonged to the domestic tradition. A major assignment in the homeland was the sculptures in the park in Tîrgu-Jiu.

At the beginning of the communist era, visual art was adapted to socialist realism in close connection with Soviet models. From the 1960’s and until the fall of the Ceauşescu regime, the forms were freer, more modern, while many of the ideological requirements remained.

Architecture

In the 20th century Romania has had a rich and old-fashioned wooden architecture, spread throughout the country. During the Middle Ages, Transylvania’s Saxon cities were in close contact with Western and Central Europe. the Romanesque Cathedral in Alba Iulia and the Gothic so-called Black Church in Brașov. In Moldova and Valakiet, the building culture was Byzantine. Striking examples are the monastery basilica of Cozia (1388) and the cathedral of Curtea de Argeș (1512) with domes on high, twisted tambourines. Noteworthy are also the one-of-a-kind Moldovan monastery churches with paintings also on the facades. The Byzantine tradition was united around the turn of the 1700’s with impulses from the Renaissance and from Islamic architecture in the so-called Brâncoveanu style, represented in i.a. Hurezi Monastery (1694) and Mogoșoai Palace (1702).

Communist Romania’s great example of “national form and socialist content” is the mighty Casa Scînteii in Bucharest (1956) by Horia Maicu. Typical of 1960’s and 1970’s modernism are the seaside resorts on the Black Sea coast. During the last time of Ceaușescu, a monumentalization of Bucharest began. Like the plans for rural modernization, it resulted in extensive demolitions of older buildings.

Music

Folk music

Romania’s rich and varied folk music, compiled and published by, among others, the Hungarian composer Béla Bartók and the composer and musicologist Constantin Brăiloiu (1893–1958), still has a strong position and great importance for the music life.

The older folk music is modal, has a small scope, usually falling melody line and strong elements of improvisation, while the newer is often built on modern Western European models, but also Oriental, mainly Turkish. Significant parts of folk music are linked to the shepherds’ lives and professional pursuits or to specific life and season rituals and ceremonies. These include Christmas songs (colinde), lamentations over the dead (bocetul) and wedding songs (cîîntecul miresei).

Common genres are doina (free-rhythmic songs or instrumental pieces), cîîntecele bătrînești (ballads) and whore (instrumental dance melodies). The most common instruments are violin (vioară), chopping board (balambal), flutes (fluier, caval, nai), bagpipe (cimpoi), lute (cobză) and accordion, often played by professional musicians (lăutari) in small ensembles (tarafuri).

Classical music

Up to the 19th century, art music was mainly linked to the Orthodox Church and to the court of nobility in larger cities. International fame reached Dimitrie Cantemir, among others, in the early 18th century.

A conservatory was set up in Iași in 1860. In Bucharest, the conservatory was founded in 1864, the Philharmonic Orchestra in 1868 and the opera in 1877. At the same time, a number of prominent amateur choirs were also formed all over Romania. Strongly influenced by indigenous folk music were George Enescu, as well as the generation mates Mihail Jora (1891–1971), Sabin Drăgoi (1894–1968), Paul Constantinescu (1909–63) and Marțian Negrea (1893–1973).

After the Second World War, more than 20 Philharmonic orchestras, ten opera houses and a large number of music schools, folklore groups and popular music ensembles were founded.

Prominent music personalities include the conductors Constantin Silvestri (1913–69), Sergiu Celibidache and Sergiu Comissiona, composers Anatol Vieru (1926–98) and Aurel Stroe (1932–2008), pianists Dinu Lipatti and Radu Lupu (born 1945), pan fluteist Gheorghe Zamfir, violinists Ion Voicu (1923–97) and Lola Bobescu (1919–2003), and singers Ludovic Spiess (1938–2006), Virginia Zeani (born 1925), Ileana Cotrubaș, Julia Varady and Angela Gheorghiu.

popular

Romania’s complex and vibrant folk music traditions form an important part of the country’s popular music development, at the same time the influences from surrounding countries and international trends have been strong. The long period of communist rule greatly influenced the music life. During Ceaușescu’s dictatorship, a standardized and idyllic image of Romanian folk music was created.

During the interwar period, the romance and folk songs Zavaidoc (1896–1945), Gică Petrescu (1915–2006) and the national icon Maria Tănase (1913–63) appeared. The jazz that also broke through at this time was banned after the Communist takeover, but the ban ended in 1964. One of the front figures in the creation of modern Romanian jazz was the pianist Johnny Răducanu (1931–2011) who also toured the United States.

The European style of striking broke through in the 1960’s with singers such as Dan Spătaru (1939–2004) and Margareta Pâslaru (born 1943).

Inspired by the American wave of folk music, in the 1970’s and 1980’s, an influential cultural movement called Cenaclul Flacăra (‘the flaming literary circle’), which, unlike other countries’ often regimental criticism, was ideologically linked to the government of Ceaușescu. Among the many artists who performed within the movement were the folk singer Florian Pittiş (1943–2007) as well as the rock group Phoenix (formed in 1962). Rock culture was seen by the communist regime as an expression of Western capitalism and liberation and repressed, but many rock bands appeared under other designations or underground. Phoenix circumvented censorship by incorporating folkloric features into the music and thus became pioneers of ethnorock which today is a great genre.

Since the 1989 revolution, the Romanian rock and pop market has expanded in many directions. Among the many style directions are the, which many consider, the over-commercialized European pop style “popcorn”, with international stars such as Inna (born 1986), Alexandra Stan (born 1989) and Edward Maya (born 1986).

Another controversial genre is the subcultural Roman genre manele, a mixture of Roman folk, Balkan and Arabic pop. The big media companies do not deal with manele, which is considered kitschy and vulgar, and in some cities the music may not be played in public. Nicolae Guţă (born 1967) and Florin Salam (born 1979) are some of the genre’s big names.

Two internationally renowned Roma orchestras based in the traditional music culture are the critically acclaimed taraf orchestra Taraf de Haïdouks and the brass band Fanfare Ciocărlia (formed in 1996). Both orchestras have toured all over the world and influenced different types of music genres. Their music is one of the quintessences of Roman musicality.

Dance

Folk dances are mostly ring and chain dances, for example. whore, but couple and man dances occur. Most dances have two-part rhythm and are based on a small number of motifs and phrases that are varied. The dances are accompanied by instrumental ensembles and often also by rhythmic exclamations and rams from dancers and audiences, strigături.

A permanent ballet ensemble was formed at the Bucharest Opera in 1885, later also in Timișoara and Cluj. After the Second World War several dance ensembles were created, of which the folklore groups in particular became very important.

folk culture

Romania’s cultural culture has been characterized by its geographical location as a transitional region between east and west. The affiliation with the other Balkan countries with regard to the age-old features of popular culture (backdrop, hand mills, primitive crops, hunting methods, etc.) is considerable, while the influence of the West – through Hungarian and German cultural contacts – has been important, especially in Transylvania. Romanian culture has played an important role as a constant and inexhaustible source of inspiration for art, literature and music to a greater extent than in most other countries in Europe.

The pre-industrial rural industries, mainly livestock management in the form of transhumance, old-fashioned dairy farming, certain age-old traits in catching methods and the collection of wild plants, have not yet played their part. The social culture (including patriarchal family system, bridal groom and bride purchase, dressing up with animal figures and joint work between neighbors) shows contacts with the Balkan countries. The building culture has great variations in the different parts of the country, from kline houses and earth holes (in Dobrogea) to the wooden buildings in knot timber.

The most well-known area of folk culture is the textile art. The national costumes show a connection with Bulgaria, the pottery has ancient ancestry. porch pillars, pompous courtyards (with important functions in social life), sticks, utensils and household items.

The country still has a vibrant and prominent ballad tradition, which has inspired modern literature. The folk music tradition is much appreciated even in urban environments; compare the section Music (above). Churches and worldly elements continue to unite during festivals and celebrations.